Stuff happens. A lot isn't by itself enough to justify its own column. Here goes a collection of stuff:

— From the department of decoding news releases:

The International Olympic Committee president, Thomas Bach, and the World Anti-Doping Agency president, Sir Craig Reedie, held a meeting Monday at IOC headquarters in Lausanne, Switzerland, after which the IOC issued a statement that included remarks from both men. From Bach: “There was a very positive atmosphere in our meeting today, and I am very happy that any perceived misunderstandings could be clarified. We agreed to continue to work closely together to strengthen the fight against doping under the leadership of WADA.”

Translation: Consider this a real step forward because it looks like WADA has been asked to drive how doping reform gets delivered.

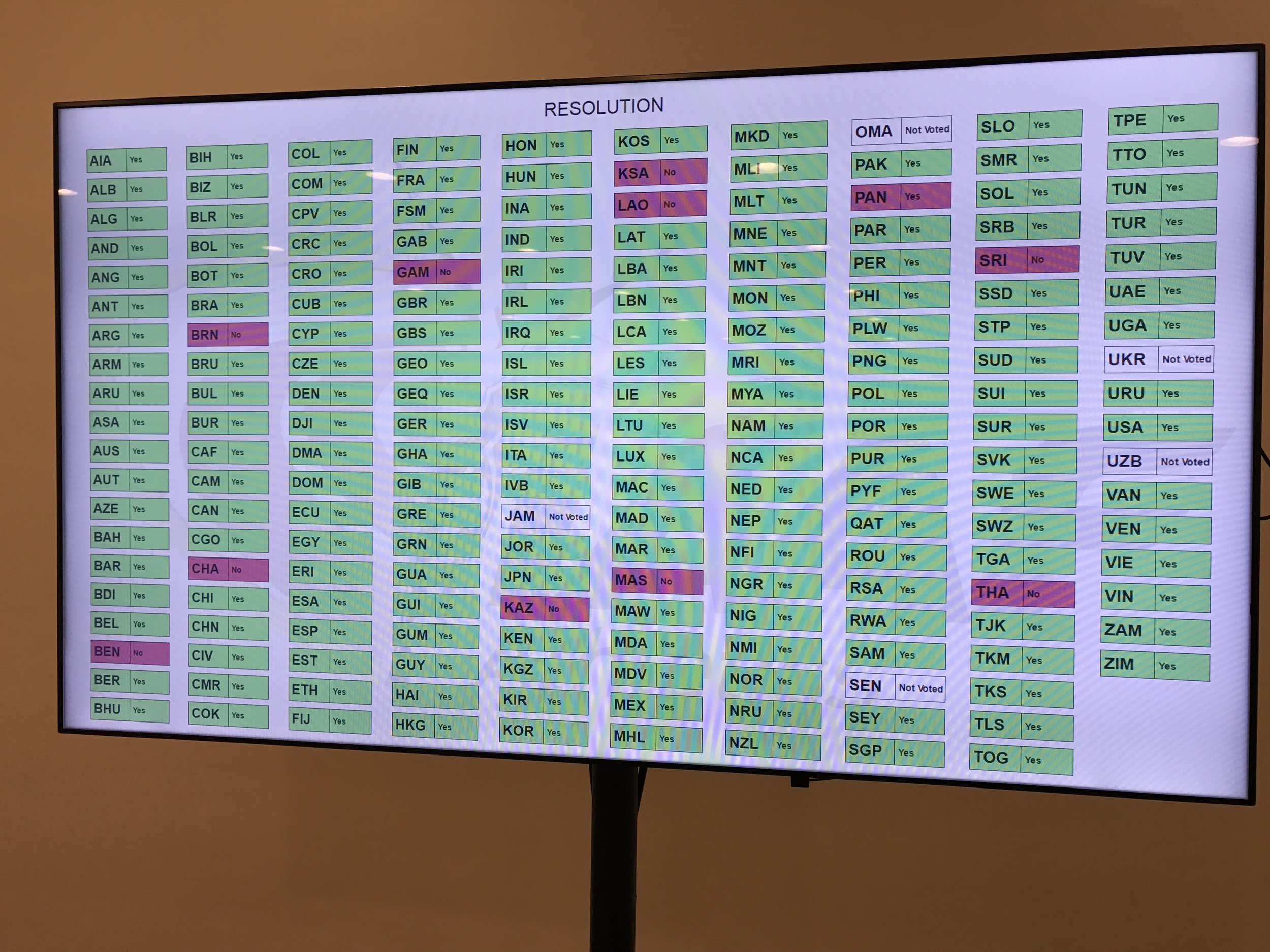

— News: IAAF enacts wide-ranging reform plan at Saturday vote in Monaco. The count: 182-10.

The IAAF reform vote may have looked like an election result from the Communist days, with 95 percent in favor, but reality is that what the vote does is give IAAF president Seb Coe time and some structure to begin what is sure to be a lengthy, arduous and contentious process of reform.

The IAAF amounts to a classic business-school case — better, a book waiting to be told — about how to rip up one structure, the president-as-unchallengeable-king model by which the federation was run for more than 30 years, and replace it with a 21st century model featuring a president, an empowered chief executive officer and more. Change is never easy, no matter the scene, and it won’t come easily to the IAAF.

— How do you know change is going to be a slog? Because of the finest part of the IAAF meeting: the moment when the delegates realized that, yes, their votes were going to be made public and they were going to be accountable for pushing the electronic vote-system button. Yikes!

Even better: Ukraine abstaining. Home of Sergei Bubka, whom Coe defeated in 2015 for the IAAF presidency. Senegal abstaining. Home of Lamine Diack, the former IAAF president, now under criminal investigation in France. Jamaica abstaining? Seriously? When anyone with an ounce of common sense knows that doping protocols in Jamaica have over the years been, at best, lackluster? If you were a Jamaican representative to some IAAF commission or another, please consider handing in a resignation letter, and pronto. Before you get, and appropriately, kicked off.

— For the history books:

Coe at one point before the vote made like Winston Churchill or something, declaring, “The greatest symbol of hope for our future is the civilized discourse we have had, its firmness of purpose and its sense of justice.”

— That 95 percent vote? That is in large part due to Coe’s political skills. He knows how to close a deal. He also knows how to delegate his proxies, chiefly among them the American delegate Stephanie Hightower. He, she and others were working it, and hard, at the IAAF gala Friday night before Saturday’s vote.

Looking ahead: the IAAF is now mandated to have female vice presidents: at least one by 2019, two by 2027. In this context, it is worth remembering the — use whatever descriptive you want — observation of the-then IAAF vice president Bob Hersh at a public USA Track & Field board meeting not so long ago that it was unlikely a woman could be elected an IAAF vice president. He also said, “We need a seat on the executive board and I have a better chance of getting that seat than Stephanie and by a large, large margin.” As ever, time reveals all things. At the IAAF elections in 2015, Hightower was elected to the council as the highest vote getter for one of six seats designated to be filled by women. She got 163; next best, Nawal el Moutawakel of Morocco, an IAAF council member for 20 years and IOC member since 1998, with 160.

— It’s also worth recalling all the senseless outrage that attended the USATF board decision to put forward Hightower, not Hersh. The time is now for Mr. Hersh, as well as all the complainers, and in particular those in the media who gave undue weight to those complaints, to apologize — to say to Stephanie Hightower, hey, sorry, we were dead-on wrong.

Let’s review:

"But I do know that at this meeting she was full of shit, so that’s not a good start. She completely disregarded the wishes of the people she is meant to represent. She did not lose honorably" -- Lauren Fleshman in a post on her blog about the December 2014 USATF annual meeting, referring to Hightower.

For emphasis, more from Ms. Fleshman:

https://twitter.com/laurenfleshman/status/541051730016743424

So over the weekend Ms. Fleshman was voted onto the USATF board, as an athlete advisory committee member. Congrats to her. Maybe while on the board she will find renewed purpose in collegiality and an understanding that perhaps things aren't always as black and white, and given to outrage on Twitter, as they might seem.

Then there was this, from the distance runner David Torrence, part of a lengthy message string he put out on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/David_Torrence/status/541045226408665088

This would be the same David Torrence who ran for Peru in the 5000 meters at the Rio Olympics rather than take his chances at the U.S. Olympic Trials. In Rio, Torrence finished 15th. Behind three Americans, among them silver medalist Paul Chelimo.

As this space has advocated on many occasions, the level of civility in and around USATF needs to be ratcheted way up and the volume on complaints turned way down. This episode — Hightower and Hersh — offers compelling evidence why, and on both counts, civility and volume. It's just way better policy for everyone to talk to and with each other instead of resorting to insults or epithets. As Coe put it: "civilized discourse."

— Mr. IOC President, please institute an IAAF-style transparent vote system for the bid-city balloting, and do so in time for the 2024 Summer Games election next Sept. 13 in Lima, Peru.

Otherwise, despite your assertions that the IOC’s own reform package, Agenda 2020 (approved by the members in December 2014, also in Monaco), is indeed meaningful, reality suggests its impact is minimal, and particularly if it can't own up to the acid test. What good is purported "reform" if the most important election in the IOC system is consistently underpinned by a culture and protocols in which everyone lies, cheerfully, to everyone else, knowing there’s zero accountability?

— The IOC president, meanwhile, is now on record as saying that without Agenda 2020 there would have been no, zero, bids for 2024. This is absurd. Los Angeles, Paris and Budapest would all still gladly be bidding.

A skeptic might say: five cities started the 2024 race and, amid Agenda 2020, only three remain.

Hamburg’s voters turned down a bid. Rome is now out, too.

Meanwhile, a Tokyo government panel has said costs for the 2020 Games may exceed $30 billion, roughly four times the bid projection, unless cuts are made. At a conference last week, the IOC declined to sign off on a $20 billion Tokyo 2020 budget, seeking a lower number.

— Both Etienne Thobois and Nick Varley were key players in Tokyo’s winning 2020 bid. Nick was the 2020 messaging guy. Etienne served on the IOC’s evaluation team for 2016 — a race in which Tokyo came up short — before switching to the bid side and being involved on behalf of the winning Tokyo 2020 project in many key elements, including the bid’s finances and budgets.

Both now serve in key roles for the Paris 2024 campaign. Varley is playing a significant role in seeking to craft a winning Paris 2024 message. Thobois is the bid’s chief executive officer.

Here is where things get awkward.

Tokyo’s bid was centered on a plan to keep most of the competition venues within five miles of the athletes’ village. Confronted with spiraling costs, the organizing committee has since done a massive re-think, and several venues may now well move outside the city.

Thobois, in a story reported a couple days ago by the Japan Times, said this:

“I think Tokyo tried to win the Games at a time when Agenda 2020 was more or less not there. So you were trying to build some kind of fairy tale.”

What?! Fairy tale?! Seriously?

He went on:

“That concept that everything was within eight kilometers was leaning into a lot of constructions, and venues that turned out not to be needed. In our case it’s very different. So the delivery model is definitely very different and I don’t think you can compare the two situations.”

Actually, yes you can. And it’s illogical not to do so. The two guys who played leading roles in selling a “fairy tale” three-plus years ago are now trying to sell — what?

“We are talking about $3 billion for the Games, infrastructure-wise,” Thobois also said about the Paris 2024 bid, according to the Japan Times, “which is very modest.” The Paris budget proposal: $3.4 billion for operations, $3.2 for infrastructure.

Who can believe those figures? If so, why?

—

There’s also this, from a lengthy November 2013 Q&A with both Varley and Thobois, Etienne observing about the winning 2020 vote:

“Tokyo were able to secure some really heavyweight, influential votes — to me that was the key. Once you secure those big leaders, those influential voters within the IOC, then things start going your way quite quickly. [Olympic Council of Asia president Sheikh Ahmad al-Fahad] al-Sabah is obviously a very influential vote to get, but on the doping issue a guy like Lamine Diack, president of arguably the biggest federation [the IAAF], quite a senior, well-respected figure, and he was clearly supporting the Tokyo bid and that was a very strong asset. There were others like that, too.”

Uh-oh.

Again on Diack, that "senior, well-respected figure":

Diack is now the target of a French criminal investigation, and primarily because of “the doping issue.” The authorities allege that as IAAF president he ran a closely held conspiracy designed to, among other things, collect millions of dollars in illicit payments in exchange for making Russian doping cases go away.

—

Another thought on Paris 2024:

If you asked someone, hey, do you want to go to Paris for, say, the weekend, the answer would of course be yes. Who wouldn’t? Look, I had one of the most glorious summers of my life there, as a student in the 1980s. But in the bid context, that’s not the central question. It’s, do you want to go to Paris and turn over your life — oh, and by the way, the future of the Olympic franchise — to the French authorities for 17 days? Answer away. No fairy tales, please.

—

Last Friday, the LA2024 bid committee released a new budget plan. It’s $5.3 billion with no surplus and a $491.9 million contingency.

Easy math: $5.3 billion is roughly one-tenth the figure associated with the Sochi 2014 Games. It’s maybe a quarter of what may be on tap in Tokyo.

A first pass at the LA 2024 budget, prepared in the summer of 2015, called for a $161 million “surplus.” That is Olympic talk for “profit.”

Let’s be real. Even if the bid committee can't and won't say so, any Games in Los Angeles is going to make a boatload of money. The only thing that needs to be built is a canoe venue. Everything else already exists; this means infrastructure costs would be super-minimal. The 1984 Games made $232.5 million. The last Summer Games in the United States was 1996. Economics 101: there’s huge demand, especially from corporate sponsors, and the supply has been cut off for going on 20 years now.

Further, California is now the world’s sixth-largest economy, with a gross state product of $2.5 trillion in 2015 — up 4.1 percent, when adjusted for inflation, from 2014. In August, California added 63,000 new jobs — that represents a whopping 42 percent of new jobs added in the entire United States.

This new pass at the budget eliminates the $161 million surplus. It throws all of it into “contingency.”

Now some first-rate analysis from Rich Perelman. Rich’s background in Olympic stuff goes back a long way. In 1984, for instance, he ran press operations at the Los Angeles Olympics; he then served as editor of the Games’ official report. This summer, he launched a newsletter called the Sports Examiner. In Monday’s edition, he offered this take on the LA 2024 plan:

“This is incredibly smart for several reasons. First, it eliminates any plans by outside groups to spend that surplus in 2025 and beyond before it is earned. Second, a zero-surplus budget looks good to the State of California, which has guaranteed to pick up any deficit of up to $250 million at the end of the Games. Third, having no announced surplus allows a clever organizing committee leadership to leverage the need to keep expenses down and obtain maximum outside support from both the private and public sectors in the run-up to the Games.”

—

Flashback to the SportAccord convention in Sochi in 2015. Then then-president of the organization, the International Judo Federation president Marius Vizer, called the IOC system “expired, outdated, wrong, unfair and not at all transparent.”

Bach’s IOC proxies, led by Diack, mounted a furious response, and Vizer resigned from the SportAccord job about six weeks later.

Vizer, as many have since said quietly, was 100 percent right. And Diack now?

The anti-doping system currently allows athletes to use otherwise-banned products with a doctor’s note and official approval. That approval is called a TUE, a therapeutic use exemption. The Fancy Bears hack suggests TUE use has been exploited if not manipulated.

Speaking to the British website Inside the Games amid the weekend Tokyo judo Grand Slam, Vizer suggested a novel approach to athlete TUE use — if you have one, you can’t compete.

“My opinion,” he said, “is that those athletes which are using different therapies should not be accepted into official competition during the effect of these products.”

Vizer’s comment is significant for any number of reasons. Here’s the most important collection: he’s almost always right, he isn’t afraid to speak out and, unlike many who just complain, he is consistently in search of and willing to suggest solutions.

—

News item: American and other athletes weigh boycott of 2017 world bobsled and skeleton championships set for Sochi.

Responses:

1. William Scherr, a key player in Chicago’s 2016 bid, said this the other day on Facebook, speaking generally about the Olympics, and it’s spot-on:

“The Olympics are the only time where the world gathers together, puts aside differences and celebrates those things that make us similar. We learn about people and cultures that we otherwise would never know, and we learn that despite being separated by distance, ethnicity and beliefs that we run, fight, swim and jump the same way.”

A boycott is just dumb. History has shown that the only people a boycott hurts are athletes. Those athletes weighing their 2017 worlds options might want to consider history.

2. No matter the context, neither sanctimonious righteousness nor rush to judgment rarely make for a winning play. If the Americans, for instance, think that doping is only going on in Russia — that’s funny. If the Americans, for instance, think that there is no link in many minds elsewhere between, on the one hand, Lance Armstrong, Marion Jones and many more and, on the other, U.S. sports success — that’s funny. That we in the United States might go, wait, the allegation is that in Russia it was state-supported — that’s a distinction that in a lot of places many would find curious. The fact is, we don’t have a state ministry of sport in the United States. So of course world-class cheating would be undertaken in the spirit of private enterprise.

3. The allegations involving the Russian system are extremely serious, and the report due out Friday from Canadian law professor Richard McLaren, with yet more accusation, is likely to be even more inflammatory. But accusation without a formal testing of the evidence is just that — accusation. All the Americans claiming the moral high ground right now — if you were accused of something, wouldn’t you want the matter to be tested in a formal setting, meaning in particular by cross-examination? Let’s just see, for instance, what comes out — whether Friday, before or after — about the credibility of Grigoriy Rodchenkov, the former Russian lab director now living in the United States.