A dozen musings on track and field, on the 2024 Summer Games bid race and more:

1. At a news conference Friday in Eugene, Oregon, before Saturday’s line-up of events at the 42nd annual Prefontaine Classic, the question went out to Aries Merritt, the 2012 London men’s 110-meter hurdles champion who is also the world record-holder, 12.8 seconds, in the event: on a scale of one to 10, where did he fall?

Heading toward the U.S. Trials in a month and, presumably, beyond to the Rio 2016 Summer Games, Merritt has probably the most unbelievable, incredible, authentic story in track and field. He had a degenerative kidney condition. With almost no kidney function, he somehow won a bronze medal in the hurdles at the 2015 world championships. Thereafter, with his sister as the donor, he underwent a kidney transplant. It required not just one but two surgeries.

So — one to 10? “Ten,” he said. Which means that the hurdles, always one of the best events at the track, figures to be that much better. And, America and beyond — get ready, via NBC and every outlet out there, for the Aries Merritt story. He deserves every bit of good publicity he gets.

2. With all due respect to the sainted Steve Prefontaine — no snark or sarcasm intended, only a full measure of respect — a significant chunk of the problem with track and field in the United States is Steve Prefontaine.

Every sport needs heroes. Not just legends.

The elements of the Prefontaine story have been well-chronicled: the U.S. records at virtually every middle- and long distance event, the fourth in the 5k at the Munich 1972 Games, his life cut short in a car crash at 24.

The legend of Prefontaine, and appropriately, has had a longstanding hold on the U.S. track and field imagination.

But imagine if, say, baseball was stuck in the Roberto Clemente era. Or the NBA fixated on Reggie Lewis, Len Bias, Malik Sealy or, for that matter, Drazen Petrovic. Or the NFL on Junior Seau and others.

One of the major challenges with track and field now is that there is no 2016 version of larger-than-life Prefontaine. No one is that guy (or that woman). Ashton Eaton could be and maybe should be. But who else? Merritt? It's anyone's guess.

Most Americans, asked to name a track and field star, will answer: Carl Lewis.

It has been roughly 20 years since Lewis made any noise on the track itself, more than 40 since Prefontaine was alive. Meanwhile, fourth-graders all around the 50 states can readily debate (pick one) Peyton Manning or Tom Brady, whether Derek Jeter was the best Yankee ever, whether they would start an NBA team with (pick one) LeBron James or Steph Curry.

Every sport, to repeat, needs heroes. Not just legends.

3. Earlier this year, the former 800-meter world champion Caster Semenya made even hardened track geeks go, whoa. She raced, and won, three events — on the same day — at the South African national championships, the women’s 400 (personal-best 50.74), 800 (1:58.45) and 1500 (4:10.93, outside Olympic qualifying time).

So much for the theory — oft-advanced by track freaks who never bother to, say, watch swimming — that a world-class athlete can’t race, and win, multiple events on the same day.

From start to finish, Semenya ran the three races in about four hours.

She went 1:58.26 to win the Doha Diamond League meet in early May, winning by nearly an entire second.

On Sunday, and she wasn’t even really going all out, Semenya ran 1:56.64 for the win at the first IAAF Diamond League meet in Africa, in Rabat, Morocco. She won by more than a full second.

For comparison: on Friday night, on Day One of the 2016 Prefontaine Classic at historic Hayward Field, American Alysia Montaño-Johnson won the women's 800 in 2:00.78.

Semenya doesn’t deserve to do anything but get to run, and run as fast as possible. At the 2009 world championships in Berlin, she ran away with the 800, in a crazy-fast 1:55.45. Then it was disclosed that she had elevated testosterone levels. The gender testing — and, more, the shaming — that she endured thereafter proved unconscionable.

The rules are the rules. The rules say she can run in women’s events.

The real question is: what should be the rules?

Because it’s perhaps not that difficult to explain why Semenya is — after silvers in the 800 at the 2011 worlds and 2012 Olympics and then injuries and subpar performances since — running so fast again now.

It’s all about testosterone levels.

Because of Semenya, track and field’s international governing body, the International Assn. of Athletics Federations, as well as the International Olympic Committee, put in place a new policy: you could run in women’s events if your testosterone levels fell under a threshold of 10 nanomoles (that’s what it’s called) per liter. In scientific jargon: 10 nmo/L.

Context: as the South African scientist and writer Ross Tucker points out in a brilliant Q&A on what is called “hyperandrogenism” with the activist Joanna Harper, 99 percent of female athletes registered testosterone levels below 3.08 nmo/L.

From the science department, part I: “hyper” is science talk for what in ordinary speech might be described as “way, way more.” The primary and probably most well-known “androgen” is testosterone.

Part II, simple math: the upper limit of 10 is more than three times higher than for 99 in 100 women.

Last year, in a decision that pleased human rights advocates but left knowledgable track observers puzzled (to say the least), sport’s top court, the Swiss-based Court of Arbitration for Sport, ruling in the case of sprinter Dutee Chand from India, said the IAAF (and IOC) could no longer enforce the testosterone limit.

In real life, and particularly as we look toward Rio, this means what?

The IAAF and IOC are trying to come up with a new policy.

In the meantime, Semenya, “plus a few others,” as Tucker writes, “have no restriction.” The erasure of the limit has “utterly transformed Semenya from an athlete who was struggling to run 2:01 to someone who is tactically running 1:56," Tucker goes on to say, adding, "My impression, having seen her live and now in the Diamond League, is that she could run 1:52, and if she wanted to, would run a low 48-second 400 meters and win that gold in Rio. too.”

He also writes that Semenya is “the unfortunate face of what is going to be a massive controversy in Rio” — my words here, not his, about who is a “female” and gets to run in “women’s” events. He writes, "It won’t be any consolation to Semenya, [that] the media, frankly, have no idea how to deal with this – nobody wants it to be about the athlete, and it certainly is not her fault. However, it is a debate we must have, and I want to try to have it from the biological, sporting perspective, and steer clear of the minority bullying that so often punctuates these matters.”

Tucker is right. The debate — calm voices only, please — needs to be held, and in short order.

4. UCLA, per a report first from ESPN, landed the biggest college sports apparel deal ever, with Under Armour. Terms: 15 years, beginning in July 2017. The deal is believed to be worth $280 million.

Biggest-ever is likely to be relative, depending on what comes next.

Because, in recent months:

Michigan, 11 years (option to extend to 15), Nike, $169 million,

Texas, 15 years, Nike $250 million.

Ohio State, 15 years, Nike, $252 million.

Boosters of these schools, and others, typically tend to react with glee at these sorts of numbers.

Rhetorical question, part I: why, when USA Track & Field chief executive officer Max Siegel scores a $500 million, 23-year deal with Nike, do some number of track fans bemoan Nike’s influence as a death star of sorts and claim the federation is verging on stupidity if not recklessness?

Rhetorical question, part II: how is it that dismissive claims about the USATF/Nike deal become gospel among the disaffected when track athletes actually get paid to run for a living but college athletes, as UCLA quarterback Josh Rosen noted in a Tweet that quickly got deleted, don’t — and likely won’t —get to see a dime of any of those millions?

Just a thought here: maybe Siegel was, you know, ahead of the power curve.

5. More on USATF, now on the dismissal this week per 11-1 vote of the federation’s board of directors of the Youth Executive Committee and its chairman, Lionel Leach:

Many, many things could be said here about Leach and the conduct that led to this action.

For now, this will suffice:

This is a movie whose ending we can all know, and now.

Why?

Because it’s a re-run.

What’s at issue, at the core, is a power struggle between the volunteers and professional staff.

Here’s news: the professional staff is going to win. As it should.

It used to be that the U.S. Olympic Committee found itself consumed by precisely this sort of petty, personalized politics. That changed when governance reforms became real; when the board empowered the chief executive to run the show; and when the chief executive proved professional and hugely competent (USOC: Scott Blackmun, USATF: Siegel).

It's a fact that USATF has a long and contentious history. But this is a fact, too: Siegel's first four years have shown dramatic, and consequential, improvement for the federation, and the sport.

6. Moving along, to an international sports federation president who also gets it, even if the IOC often doesn't want to admit so: Marius Vizer, president of the International Judo Federation.

Vizer, in advance of the start Friday of a major IJF event in Guadalajara, Mexico, spent about two hours doing a live Q&A on Twitter.

https://twitter.com/MariusVizer/status/736270089708703744

Imagine: actually doing exactly what the IOC says it wants to do, to reach out to young people in those ways, like Twitter, by which young people connect with each other.

Far too many federation presidents might have something resembling a panic attack at the thought of entertaining questions about whatever from whoever. Vizer, who has never had anything to hide and has consistently been a forceful voice for accountability and change (to the IOC's chagrin), made it plain: bring it on.

Indeed, Vizer ended by saying more such Q&A's would be forthcoming.

https://twitter.com/MariusVizer/status/736291453161246722

7. Switching to 2024 bid news:

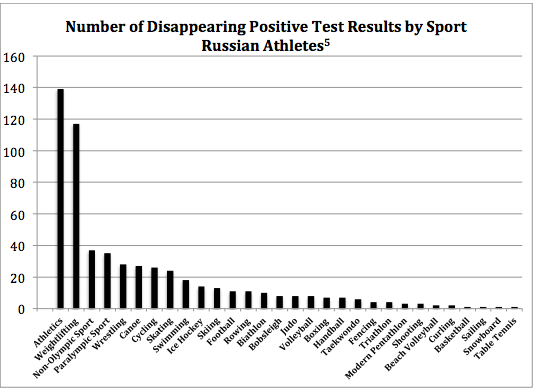

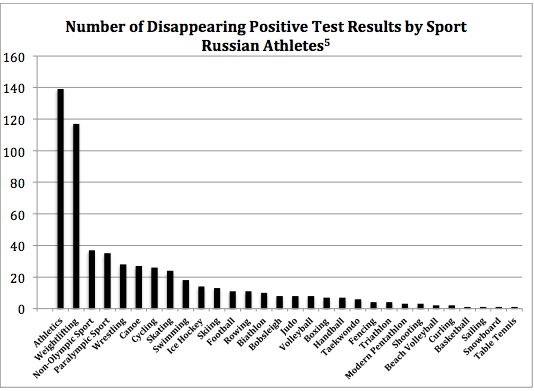

If you might be tempted to look past those potentially significant developments related to the allegations of Russian doping — first, a potential U.S. Justice Department inquiry and, second, U.S. Anti-Doping Agency chief Travis Tygart’s bombshell of an op-ed in the New York Times — it was otherwise a good week for the LA24 bid committee, at least for those things it could and can control.

Los Angeles, behind a bid headed by Casey Wasserman, who is also in charge of LA24, won the right to stage the 2021 Super Bowl.

Plus, a rail line from downtown to Santa Monica opened, to real excitement and big crowds. Roll that around in your head: LA. Rail. It’s real. Really.

8. Still a long way to go in the 2024 race, which the IOC will decide by secret ballot in September 2017 at a meeting in Lima, Peru. Three others are in the race: Paris, Rome, Budapest.

It’s a proven that what wins Olympic elections are, first, relationships, and two, telling a story that will move IOC members emotionally.

Right now, only two of the four are telling a real story: Los Angeles. And Budapest.

9. Turning to the 2020 Summer Games campaign, won by Tokyo:

The Japanese Olympic Committee announces a three-person investigation of allegations of bribery. This from the same place that brought you the burning of the Nagano 1998 books so as to avoid embarrassing the IOC.

Let’s all wish for really good luck in getting a genuine answer.

Why in the world would you need to send $2 million to Ian Tan Hong Han, a consultant based in Singapore, who is close friends with Papa Massata Diack, son of Lamine Diack, the then-president of the IAAF, when virtually no one in the Singapore international sports community knew of Han or his firm, Black Tidings?

Black Tidings had precisely what know-how to provide such high-level consultancy services?

More: those who were there for the Singapore 2010 Youth Games know there had to be external help when Singapore was bidding for YOG. Curious.

10. Russia uses sports as an instrument of what’s called “soft power,” meaning president Vladimir Putin has sought to use sports to project a Russian image of strength, not only abroad but, crucially, within Russia itself.

The United States, which under President Obama has clashed with the Kremlin over issues ranging from the disclosures of the activist Edward Snowden to the composition of the formal U.S. delegation to the Sochi 2014 Winter Games, has if not unparalleled then at least significant resource available to its spy agencies.

How is it that Sochi 2014 lab director Gregoriy Rodchenkov could flee Russia and end up so quickly in the United States? No one in the American spy apparatus would want to embarrass the Russians, would they?

Again: just curious.

11. What a surprise! The London 2012 doping re-test positives became public on a Friday!

The numbers: 23 athletes from five sports and six countries, based on 265 re-tests

More numbers, 32 doping cases from London 2012, 57 for Beijing 2008. Previous high, according to IOC figures: 26, Athens 2004.

To reiterate a central point: you have to be frighteningly stupid to get caught doping at the Olympic Games themselves.

It’s one thing to be caught in no-notice, out-of-competition testing. But at the Games?

You know there are going to be drug tests. You know the samples are going to be kept in the freezer for (at least) 10 years to allow for advances in testing.

It has been said many times but is still worth repeating: failing a drug test at the Olympics is like failing an IQ test.

Stupid.

12. If you’re thinking of going to Rio, don’t. Sorry to say so but — don’t. Watch on TV.

The pictures will be beautiful and the only danger in overloading on TV is breathing in that funky orange-red Doritos powder.

In Brazil, meanwhile:

The case of the Spanish sailors getting held-up at gunpoint, lucky to escape with their lives, underscores the No. 1 challenge ahead of these Games. More than dirty water, or maybe even Zika, or presidential politics, or corruption scandals. More than anything. To compete, or to be at, the Games in Rio, you have to deal with life in Rio as it is. Maybe — maybe even probably — it will be fine. But one wrong misstep, even with no fault, and you might well find yourselves in a scene evoking Tom Wolfe’s 1987 masterpiece, “Bonfire of the Vanities.”

Who wants that? Be a master of your TV universe.