You know what was missing from Tuesday’s theater-of-the-absurd hearing in Congress on what was billed as “ways to improve and strengthen the international anti-doping system?”

Besides, you know, a big check or a ready-to-implement action plan aimed at improving and strengthening the international anti-doping system?

This hearing had nothing to do with either of those things, really. Nothing at all.

It was an excuse for the fine ladies and gentlemen representing various districts of Congress to take pictures with the likes of Michael Phelps and Adam Nelson — gee, who could have predicted that? — and, more to the point, play to the C-SPAN cameras while bashing Russia and touting truth, justice and the American way.

All the while coming off like the camera-seeking hypocrites that skeptics might suggest they are.

Representative Greg Walden, a Republican from Oregon: “Now you’re going to give us confidence that … U.S. athletes, who play by the rules, can compete against other athletes who play by the rules?”

“Thank you,” a smiling Representative Kathy Castor of Florida, a Democrat, told Travis Tygart, the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency chief executive, “for having the intestinal fortitude to stand up for our athletes and clean competition around the world.”

Oh! So that’s what this was about!

“Our” athletes, not “ways to improve and strengthen the international anti-doping system”?

Who woulda thunk?

There were so many choice moments during this nearly 150-minute paean to America the beautiful before the Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives' Energy and Commerce Committee (whew).

It was so stirring you might well have expected all in attendance to brandish special cereal-box Captain America power shields if, say, Ivan Drago had bolted into Room 2123 of the Rayburn Building to announce that, of course, he was there to break each and every one of them.

Maybe the best moment, however, was when Rep. Frank Pallone Jr., a Democrat from New Jersey, clearly reading from notes prepared for him, misspoke and referred to the “bobsled and skeletal federation.”

It’s “skeleton.”

There’s so much wrong with Congress having hearings on an issue the elected ladies and gentlemen know virtually nothing about and, more to the point, can’t and aren’t going to do anything about.

But Mr. Pallone’s glitch is altogether so revealing.

So, too, the rhetoric, which in an effort to make one point simply proved the other.

“It starts with the athletes. They own the culture of sport,” Tygart asserted.

“And it’s wonderful — it’s sad it took this scandal to mobilize them in the way that it has but it’s wonderful that they’re now mobilizing and realizing how important this right is to them. They also have to have confidence in the system.”

You'd think it was 1984 all over again, and Marty McFly had just parked his DeLorean on Capitol Hill with the cassette tape blasting Bruce Springsteeen's "No Surrender," or something.

Soviets? Russians? Which? Whatever.

Oh. Still us and them. Got it.

But wait, just to put what Tygart said in some context:

Phelps said he didn’t believe he had ever competed internationally in a totally clean event. Nelson, too.

So what is the only reasonable, logical deduction about the so-called “culture of sport”? The brutal truth?

Athletes all over the world cheat, and if they can get away with it, they damn sure will.

Why?

Because, again, logic:

Illicit performance-enhancing drugs work.

Following that to the stark conclusion:

For many athletes in whatever country — and don’t be fooled, the United States has produced some whopping world-class cheaters — the risk-reward ratio makes for an easy tilt.

Indeed, if you were in the Russian Duma, following Tuesday’s spectacle in Congress, why wouldn’t you hold a hearing in which you splashed pictures on a really big screen and howled in laughter at Lance Armstrong, Floyd Landis, Tyler Hamilton, Marion Jones and scads of baseball stars?

In the background, you could work up a digital sampling loop of Mr. Walden from Oregon saying, “U.S. athletes, who play by the rules …”

Oh, again — in Russia the defining difference is, according to the second of the 2016 reports produced by the Canadian law professor Richard McLaren, “institutional control”?

All that does is point up what happens when you have a federal sport ministry, like they do virtually everywhere else, and when you don’t, as is the case in the United States.

Here, we do our cheating red, white and blue capitalist-style:

To quote Ivan Drago's movie wife, the equally awesome Ludmilla, dismissing allegations that her husband could have used steroids: "He is like your Popeye. He eats his spinach every day!"

Just to underscore the raging hypocrisy of Tuesday’s hearing:

Dial the history books back to 2012, a couple of months before USADA tagged Mr. Armstrong.

That summer, a longtime Wisconsin Republican congressman, Representative Jim Sensenbrenner, sent a letter to the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, the funnel for significant USADA funding, declaring, “USADA’s authority over Armstrong is strained at best.”

Also included were even more laff-out-loud party lines:

“Armstrong, however, has never failed a drug test despite having been tested over 500 times.”

“As attorneys for Armstrong asserted, ‘USADA has created a kangaroo court … ‘ “

“The actions against Armstrong come in the midst of inconsistent treatment against athletes.”

Mr. Sensenbrenner, still a member of Congress, was at the time the chair — he still sits on — the House Judiciary Committee’s subcommittee on crime, terrorism and homeland security. That panel held jurisdiction over ONDCP. Moreover, Mr. Sensenbrenner’s district is home to the then-longtime Armstrong sponsor, Trek Bicycles.

Big picture take-away from Tuesday’s event:

The anti-doping campaign is not easily reduced to sound bites and headlines.

It’s complicated.

Making any sort of real progress is going to take way less rhetoric, far more cooperation and considerably more cash.

This field is simply not susceptible to Tuesday's display of red, white and blue.

Or, more to the point, black and white. It’s a lot of grey.

— Russia bad, Russia bad, Russia bad. Got it, Congress.

Over the weekend, the International Olympic Committee, citing a Feb. 21 WADA meeting, sent out a letter referring to the pair of McLaren’s 2016 reports, from December and July, acknowledging that “in many cases the evidence provided may not be sufficient to bring successful cases.”

So even if Russia bad — it is at the core of the notions of truth, justice and the American way that each and every person is afforded the chance to test any and all evidence the authorities say they hold.

If it’s “not sufficient,” you’re free to go. In this context, to compete.

Same deal for Russians, for Americans, for whoever.

As Dr. Richard Budgett, the IOC’s medical director, put it in the statement he submitted Tuesday to Congress, “In accordance with the principles of individual justice, clean athletes should not be sanctioned or punished for the failures of others.”

— Tygart: “If you continue to have sport overseeing investigations, determining compliance, acting as a global regulator of itself, it’s no different than the current status quo, which is the fox guarding the henhouse.”

Tygart’s argument holds intuitive appeal. Moreover, he knows full well that a good many people don’t understand the anti-doping landscape, laced with science, law, politics and diplomacy, so they rely on him — indisputably an expert — to lay out for them in easy-to-follow terms (fox, henhouse) what might seem most constructive.

Fair enough.

At the same time, it’s far from crystal clear that “sport” ought to go anywhere.

Governance is rooted not just in structure but in culture. Eight years ago, the USOC tried to separate the two, when Stephanie Streeter, who had no significant “sport” experience, was named chief executive. She lasted all of a year, resigning amid a 40-0 no confidence vote from the American national governing bodies — that is, from sport.

Culture matters, a lot, and it’s also a fair argument that the anti-doping machinery ought not take significant dollars from sport while churlishly then banishing any and all goodwill, good faith and experience that comes with those dollars to the penalty box.

That’s called rude and ungrateful, and no system can sustain itself like that for long.

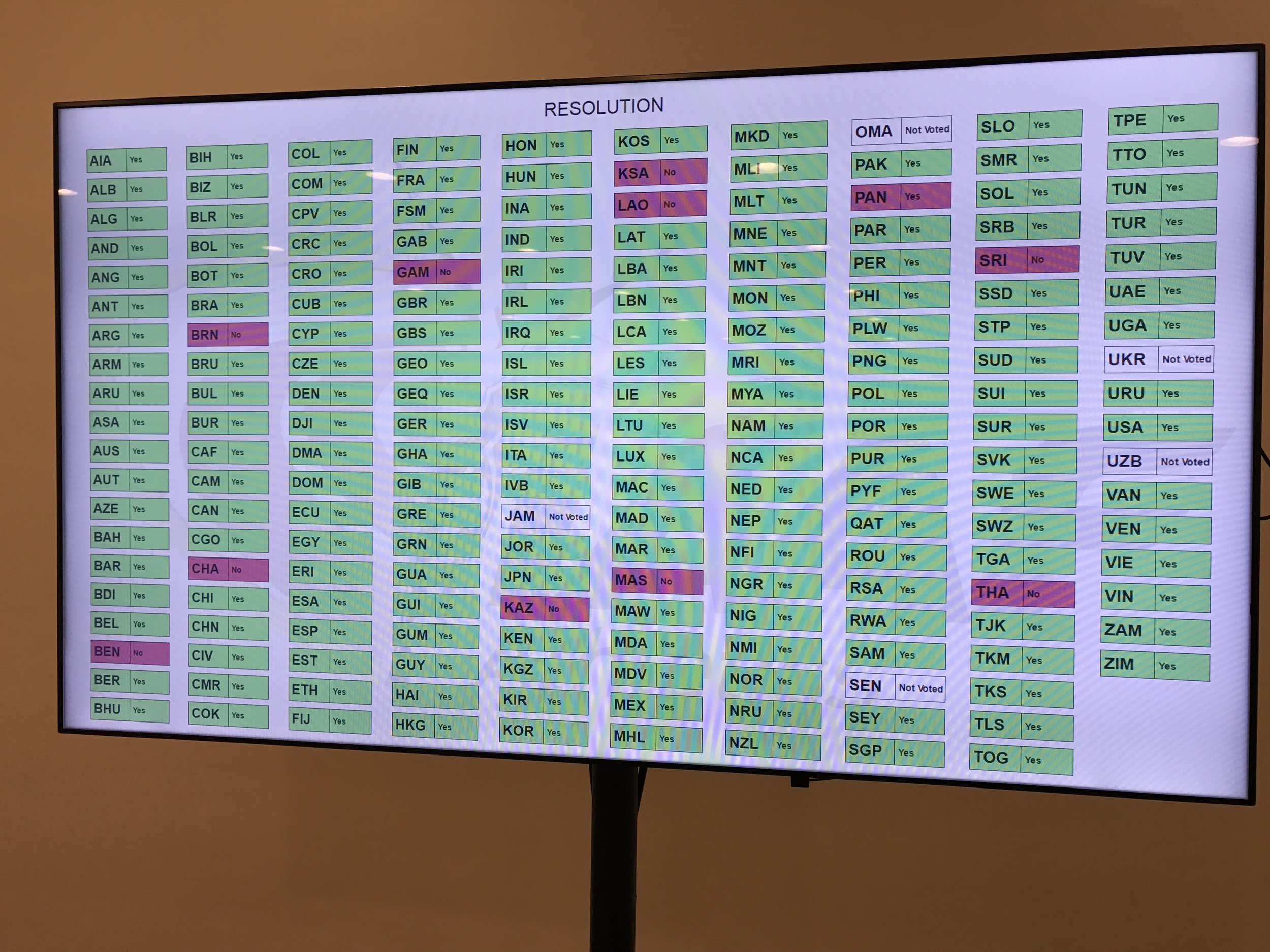

— WADA’s 2017 annual budget is $29.7 million. The U.S. government is due this year to put up $2.155 million, or 7.3 percent.

That’s way more than any other country puts up.

That’s one way to look at it.

Another view:

There are 206 national Olympic committees. The U.S. Congress thinks it’s entitled to hold hearings when the American government is putting up 7 percent toward an entity because — why?

Is any other parliamentary or legislative body in the world holding such hearings? No. Obvious question: why not?

Ethiopia recently criminalized sports doping. The new head of the country's track and field federation is Haile Gebrselassie, the distance running great. A 22-year-old marathon runner, Girmay Birahun, is now facing at least three years in Ethiopian prison after testing positive for the controversial Latvian heart medication meldonium; Maria Sharapova is due to return to the tennis tour in April after her sport ban for the same substance was cut from 24 months to 15. Ethiopia, where there's a lot to discuss in the anti-doping scene, is due to contribute a grand total of $3,239 to WADA in 2017. Not a typo — $3,239, and already has paid $3,085.

Should Ethiopia hold a hearing? If it did, should WADA and the IOC send representatives, like they did Tuesday to Washington?

Does Mr. Birahun own the "culture of sport"? Or do only western athletes, and in particular Americans?

Yet another view:

The 2016 U.S. federal budget was, ballpark, $4 trillion. Yes, $2 million is real money. But, context: $2 million over $4 trillion equals pretty close to nothing. And Congress is yapping for more than two hours?

“We can have all the governance review in the world. Which we welcome and we want. I have been in this business for 20 years. And it’s time for change. It’s time to put investment into this business,” Rob Koehler, the WADA deputy director general, said in response to a question from Representative Chris Collins, a Republican from New York.

“If I look globally at the amount of money being put into national anti-doping organizations,” Koehler said, “it’s simply insufficient. There’s the crux of the issue.”

He added a moment later, “Until that happens, we’ll never see change.”

— The U.S. Olympic Committee is giving USADA $4.6 million this year, up 24 percent from $3.7 million the year before.

That’s real investment, and the USOC should be applauded for seeking to effect real change.

— Much was made Tuesday of a WADA-commissioned report from a team of so-called “independent observers” who reported after the Rio Games that 4,125 of the 11,470 athletes on hand may have shown up in Brazil without being tested even once in 2016, 1,913 in the 10 sports deemed most at risk for cheating, among them track and field, swimming and cycling.

The problem with these numbers is that they are both entirely accurate and thoroughly misleading.

Would more testing be helpful? Probably.

But as the Armstrong case proves, being tested — or passing a test — proves absolutely nothing.

As Sensenbrenner, and even Armstrong himself, noted:

https://twitter.com/lancearmstrong/status/71358750434402306

Passing a test does not prove an athlete is clean.

This is a core misconception.

Testing is not, repeat not, a failsafe. To believe otherwise is naive in the extreme.

— In a similar spirit, it’s not unreasonable if Phelps — who has never given any indication that he is anything but an honest champion — might have had to get up at 6:05 in the morning for drug testing.

You say otherwise?

Here is the way the “whereabouts” system, as it is called, works.

It would defeat the entire purpose of out-of-competition testing for an athlete to know exactly when drug testers are coming. At the same time, it would be entirely unreasonable for Athlete X to be on call 24/7. So the system strikes a balance.

Via the sort of paperwork that Phelps noted Tuesday he repeatedly had to fill out, Athlete X makes himself or herself available to drug testers one hour a day.

Whatever 60 minutes that is — it’s his or her choice.

So, for instance, if the tester shows up at 6:05, it’s because on that form Phelps, or whoever, put, say, 6 to 7 a.m.

Phelps, referring to his baby son Boomer in responding Tuesday to Collins, the New York Republican, said, “I don’t know what I would — how I would even talk to my son about doping in sports.

“Like, I would hope to never have that conversation. I hope we can get it cleared, cleaned up by then. For me, going through everything I’ve done, that’s probably a question I could get asked. I don’t know how I would answer.”

Easy:

Just because you’re American doesn’t mean you’re good, just because you’re Russian doesn’t make you bad.

Everybody has temptations. Do the right thing, son, the way mom and I raised you.

In the meantime, it’s up to the grown-ups to make sure the people running, say, the swim meet have enough money to do every part of what they do the right way.

Also, next time mom and dad will tell those people in Washington to find someone else to take pictures with, OK? Like Ashton Kutcher. When he was doing the same sort of thing daddy did on Tuesday, Ashton blew a kiss to John McCain.