Prediction: the Russians will be at the 2018 PyeongChang Olympic Winter Games, and as Russians.

Assertion: the Russians should be at the PC 2018 Games, and as Russians.

Rationale: the central principle of the Olympic movement is inclusion.

Last December, in the second of his two World Anti-Doping Agency commissioned (but, to be clear, independent) reports into allegations of doping in Russia, the Canadian law professor Richard McLaren wrote:

“It is time for everyone to step down from their positions and end the accusations against each other. I would urge international sport leadership to take account of what is known and contained in the [two] reports, use the information constructively to work together and correct what is wrong.”

It is through that prism that one ought to view, one, the love note the International Olympic Committee dropped in classic late Friday afternoon PR-style on what it called “the reform of the anti-doping system” and, two, the sanctimonious political grandstanding sure to be coming at next Tuesday’s U.S. House of Representative subcommittee hearing on “ways to improve and strengthen the anti-doping system.”

The U.S. Congress and the IOC would do well to listen to Mr. McLaren’s wise counsel.

But no.

Turning to Congress first:

One, you might think the U.S. House of Representatives might have better things to do than hold hearings about Russian doping.

Because, like, that is the House of Representatives for the United States and the allegations about doping involve another country. That country is called Russia. Russia is not the United States.

Maybe the ladies and gentlemen of the 115th Congress might have more pressing priorities in regard to American life. Maybe, you know, jobs. Then again, it’s February. This is why Sports Illustrated features swimsuit models this time of year. It’s silly season.

Two, everything you need to know about how dumb, what an absolute waste of time and resource this hearing is going to be, can be explained in the headline to the committee news release: “Gold medal lineup: Tuesday hearing on anti-doping brings together all-star panel.” For emphasis, “gold medal lineup” is in capital letters.

Wow! Sports stars come to Washington! Congresspeople! Staffers! Get out your cellphones so you can get your selfies with witness No. 4 on the testimony list — “Mr. Michael Phelps, American swimmer and Olympic gold medalist”! Let's count! 28 Olympic medals in all! 23 gold!

Get back to me, anyone, when you tell me how many of those 28 medals Phelps — and I have been there for every single one of his Olympic races, maybe even written a best-selling book with him — has lost to a Russian swimmer.

Hint: zero.

If Congress wants to investigate some current issues involving doping in American sports, since it can turn to subpoena power and everything, here are some suggestions:

— Lance Armstrong is facing the prospect of civil trial. In February 2012, the U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles, headed by Andre Birotte Jr., abruptly dropped, without explanation, a two-year criminal investigation into Armstrong’s activities. That October, the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency made its case against Armstrong, revealing that he had, in fact, been doping for years. In April 2014, Birotte was nominated to become a federal judge in LA, where he now sits. How does that happen?

— What’s really on that Tom Brady cellphone? Even a sitting U.S. judge on a circuit court of appeals in New York, in oral argument nearly a year ago, said it made no sense whatsoever for Brady to have destroyed the phone. And is there any connection to that phone’s destruction and these kinds of stories?

— What about the extent and scope of the use of illicit performance-enhancing substances in the NBA and NFL, among other U.S. major pro leagues? Or do you, congresspeople, really think, oh, linebackers are built and run like that naturally?

Moving along:

Three: it is the height of hypocrisy for the legislative arm of the United States government to be holding a hearing into ways to “improve and strengthen the anti-doping system” when, as this space pointed out recently, the American government contributed not one penny to either of the two Pound or two McLaren reports, which together cost $3.7 million.

Suggestion: you want to improve the anti-doping system?

Easy. Like most problems, it can be made way better by throwing money at it.

WADA’s 2017 budget is $29.7 million. The U.S. government’s dues are expected to total $2.155 million. That’s by far the most of any country anywhere. Britain, Russia, Germany: $815,630 apiece.

The U.S. money has for the past several years been funneled through a White House agency called the Office of National Drug Control Policy.

But lookee here, according to a Feb. 17 New York Times account: the Trump Administration may be poised to move ahead with elimination of nine programs, most “perennial targets for conservatives.” One of the nine: ONDCP.

Now that would be something to investigate.

Particularly since — lookee over here, too — the very same Republican chair of this very same subcommittee, Rep. Tim Murphy of Pennsylvania, according to the Wall Street Journal, co-signed a letter sent Thursday to, whaddya know, ONDCP that said:

“On top of opioid overprescribing and heroin overdoses, we believe the United States is now facing another deadly wave: fentanyl.”

The way these sorts of Capitol Hearings hearings typically work is that the members and staffers stroll in, now with cellphones in hand, with a briefing memorandum.

That’s the background they get.

Meaning that’s usually pretty much the sum and substance of what they know about the topic at hand.

These sorts of memos tend to be a matter of public record. This particular memo runs to eight pages and 47 footnotes.

Of those 47, 33 are news stories, press releases, op-eds, TV shows or the Pound or McLaren reports themselves.

A good chunk of most of the others, including a bunch of the first dozen, are who-we-are and what-we-do-documents (No. 2, WADA mission statement, etc.)

So, again, what is this hearing about?

News stories, press releases, op-eds and TV shows.

Not actual reform.

That, to reiterate, would take the one thing the United States government has only marginally been, and may not now at all be, willing to shell out:

Hard cash.

Which brings us to the IOC.

Same issue.

The IOC took in $5.6 billion over the 2013-16 cycle.

In his letter, circulated widely within Olympic circles but not formally addressed to WADA itself, the IOC director general Christophe de Kepper notes that in the first WADA-commissioned independent report, made public last July, Mr. McLaren “describes a ‘state-sponsored system’ whilst in the final full report in December he described an ‘institutional conspiracy.’ "

The IOC panels now studying what’s what, de Kepper said, “will now have to consider what this change means and which individuals, organizations or government authorities may have been involved.”

Oh, please.

If anyone thinks this trail is going to lead to the cellphone of the Russian president, think again. It’s not going to be found, anyway.

Hmm. Weird coincidences, sometimes. Or not. Whatever.

Mr. de Kepper further notes that "it was admitted" by WADA that "in many cases the evidence provided may not be sufficient to bring successful cases." This is a pointed note aimed at the WADA position of an all-out Russian ban and the IOC stance in favor of individual justice. This space, almost alone in the western press, has argued that of course every single person in the world deserves to have his or her case heard on the basis of the evidence against him or her -- not a group grope.

At any rate, along with the possibility if even probability of soaring legal principle and individual justice, at issue with Mr. de Kepper's position, without doubt, is the IOC seeking advantage in a push-and-pull with WADA over who is going to control what over what comes next.

Mr. McLaren made clear what “this change means." See the second paragraph of this column: all involved should be invoking less rhetoric and seeking more cooperation.

In that spirit, here are some words of wisdom that won’t be in any of those footnotes and that won’t be referenced in that IOC letter.

They were spoken at a WADA executive meeting in September by the WADA director general, Olivier Niggli, and for sure the IOC is aware of them, or ought to be on what lawyers would call the theory of constructive notice, because an IOC vice president, Turkey’s Ugur Erdener, was in the room listening.

This sort of thing isn’t ripped from the headlines. No cellphones. No news releases touting gold-medal lineups or all-star panels.

This is the nitty-gritty of the anti-doping scene.

To make an anti-doping system work takes tons of hard grinding, along with patience, science, leadership and collaboration from sports officials and earnest government officials, and it takes a lot more money than is right now at anyone's disposal, especially WADA. The inescapable fact is the IOC has to put up that coin. Governments come and go; congresspeople pose and prance and dither; the IOC is the only big-picture revenue source with an ongoing interest in making sure international sport is as clean as can be.

That’s going to take checks and balances along with trust, will and faith.

As Mr. McLaren said, that means constructive problem-solving.

“The report,” Niggli said in September, referring to Mr. McLaren’s July document, “had generated a lot of comments and discussions over the past few months.

“WADA should not lose the focus, which was that it was an issue with Russia, and WADA still had to deal with that issue.

“It was a very important issue, and the fact that Russia had been cheating everybody for a number of years needed to be addressed. That was the key focus, and it probably should have been the focus of the discussion over the past months, too.

“Unfortunately, the discussion had been on trying to attack WADA and blame the anti-doping system, and that had not been helpful. The members should bear in mind that WADA did not operate in a vacuum.

“WADA was made up of governments and the Olympic movement, and the Olympic movement had been around the table from Day One,” in the late 1990s, “and had supported the work of WADA and the revised World Anti-Doping Code, and it had been paradoxical to see how the entire anti-doping system had been questioned after the McLaren report.

“… The system was [not] the issue; the issue was how the system was being practiced by some, and the members should not forget the fact that the system had been cheated.

“One could design a great system but if those applying it were cheating, it was difficult to achieve success.”

Exactly.

The most important note from the compelling report released Monday in a World Anti-Doping Agency-commissioned inquiry into allegations of Russian doping is super-clear and, because of that, all the more striking: there is no recommendation about what, as Lenin might have put it, is to be done.

This means the door has, purposely, been left wide-open for Russian athletes to take part in the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. As they should.

To be clear:

The report, produced by respected Canadian law professor and anti-doping expert Richard McLaren, offers evidence that strongly — reiterate, strongly — suggests the involvement of the Russian state in promulgating a program designed to evade anti-doping controls.

Over its 103 pages, the report offers up a narrative of holes in walls, disappearing positives and more.

But — and this is the key — the report does not tie specific athletes to specific misconduct. At least yet. Without that, it fails law, ethics, morality and common sense to bar anyone from Rio.

The report also — and this is essential, too — asserts, and repeatedly, that the evidence it is offering up is “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

If only that were the case.

Instead, the report is rife with internal contradictions and more that demonstrate in a vivid fashion the glaring conflict in trying to ban anyone on these grounds.

In sum, the McLaren report amounts to a prosecutor’s brief. A solid salvo. He and his team deserve considered respect. And WADA deserves applause for commissioning his inquiry.

Even so:

There has not yet been any sort of cross-examination, in a formal setting under oath, of considerable chunks of the evidence offered up in the report.

Thus calls for bans or more sparked by the McLaren report amount to howling from the mob. Not justice.

The Olympics are better than that.

The Olympics, at the core, are about fair play.

If the argument is that the Russians corrupted that ideal, the response is elemental: two wrongs do not make a right.

Neither the International Olympic Committee's policy-making executive board nor the Swiss-based Court of Arbitration for Sport -- both meeting this week to consider the Russians -- are obliged in any way, shape or form to dish out collective responsibility when every principle of fairness calls out for individual adjudication.

WADA, upon the release of the report, put out a statement urging that Olympic authorities “decline entries” from Russia for Rio. WADA is under intense geopolitical pressure. Such a statement is super-cool PR, enabling WADA to play CYA in advance of reviews from the IOC and CAS.

The close reader will also note the disclaimer in the “preamble” to the WADA statement, from president Craig Reedie. WADA, he expressly notes, “does not have the authority or remit in respect of entries to competitions.”

There are now two probable paths ahead:

One, the IOC president, Thomas Bach, has already done a deal in Russia to effect a ban for one Games. This would, among other things, serve as protection for the next major summertime sports event involving the Russians, the 2018 World Cup.

This seems unlikely.

Putin, in a statement put out Monday by the Kremlin, after noting the 1980s-era boycotts led by the United States of the Moscow Games and, then, in reprisal, by the Soviet Union in 1984 in Los Angeles:

“Today, we see a dangerous return to this policy of letting politics interfere with sport. Yes, this intervention takes different forms today, but the essence remains the same; to make sport an instrument for geopolitical pressure and use it to form a negative image of countries and peoples. The Olympic movement, which is a tremendous force for uniting humanity, once again could find itself on the brink of division.”

If you're going to ban Russia, you might want to ban Kenya while you're at it. Unlikely? If so, how is it remotely fair to ban Russia?

And this: eight years ago, literally during the 2008 Beijing Games, Russia and Georgia fought a brief war. If neither was kicked out of the Games then, and people were actually dying, the IOC would now take the step of implementing a ban (against Russia) because of -- allegations of doping?

Option Two, and far more likely:

The IOC board meeting Tuesday produces rhetoric but no more. CAS issues its decision later this week, perhaps Thursday. The IOC waits after that to “process” (pick your word) everything that’s going on. Then it waits a little bit more. The next thing you know, the IOC says it really needs more information, the sort McLaren makes plain that he has or has access to but has not yet himself processed and, oh, by the way, it’s now too late — see you in Rio, Russians.

One thing that has not been super-cool: the aggressive push from Travis Tygart, head of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, and others in the United States and Canada to keep the Russians out.

Their statement over the weekend, calling for a ban on the Russians, suggested — rightly or wrongly — that the McLaren report had been leaked to Tygart, and others, in advance. It had not.

Everyone gets the right, at least in the United States and Canada, to speak their mind. That’s not the issue. The issue is that actions lead to consequence. And — you can believe — many important and influential people in the broader sports movement are irritated, big time, and at Tygart in particular.

It’s not only that such banging-the-drum has not been helpful. Believe it — again — it actually has intensified the risk of seeing happen the exact opposite of what has been asked for.

You can like Putin, or not. Fear the Russian president. Loathe him. Respect him. Whatever. It doesn’t matter. What matters is that Putin is arguably on the top-three list of most important personalities in the Olympic movement. Putin matters. And Russia matters.

More from Putin in Monday’s statement:

“The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency and several anti-doping agencies in other countries, without waiting for the official publication of the World Anti-Doping Agency’s commission, have hastened to demand that the entire Russian team be banned from taking part in the Rio de Janeiro Olympics.

“What is behind this haste? Is it an attempt to create the needed media atmosphere and apply pressure? We have the impression that the USADA experts had access to what is an unpublished report and have set its tone and even its content themselves. If this is the case, one country’s national organization is again trying to dictate its will to the entire world sports community.”

Uh-oh.

Putin goes on to say:

“Russia is well aware of the Olympic movement’s immense significance and constructive force, and shares in full the Olympic movement’s values of mutual respect, solidarity, fairness and the spirit of friendship and cooperation.

“This is the only way to preserve the Olympic family’s unity and ensure international sport’s development in the interest of bringing people and cultures closer together. Russia is open to cooperation on achieving these noble goals.”

Make of that whatever you will. The important thing is that, unprompted, these last two paragraphs also found their way into the Kremlin release.

As Olivier Niggli, the new WADA director general, noted in the agency’s news release: “...senior Russian politicians have started to publicly acknowledge the existnce of longstanding doping practices in Russia, and have conceded that a significant culture change is required.

“The McLaren Report makes it ever more clear that such culture change needs to be cascaded from the very top in order to deliver the necessary reform that clean sport needs.”

That’s going to take time, and money. WADA needs way more than the $26 million a year it gets now, and any number of the roughly 200 nations in the world need to step up big time if the campaign against doping in sports is to become, truly, a priority.

In the meantime, there remains the pressing question: what is to be done?

Thomas Bach, the IOC president, observed a few days ago in an interview with Associated Press and other wire services:

“It is obvious that you cannot sanction or punish a badminton player for infringement of rules or manipulation by an official or lab director in the Winter Games,” the keen student noting that Reedie is a former badminton champion who went on to be president, in the 1980s, of the international badminton federation.

“What we have to do,” Bach said, “is to take decisions based on facts, and to find the right balance between collective responsibility and individual justice. The right to individual justice applies to every athlete in the world.”

Just to take one of many examples from within the McLaren report:

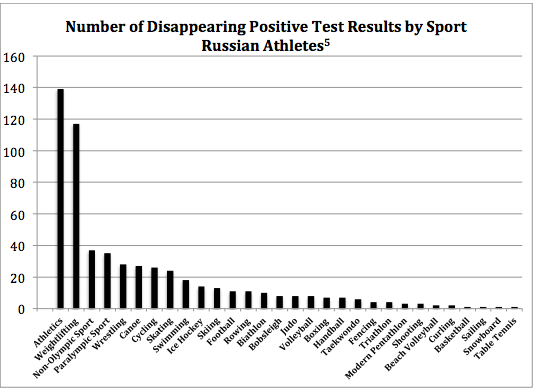

A graph, page 41, shows the number of “disappearing positives” in various sports.

The Russian synchronized swim team is a powerhouse. Is there any mention of synchro on that list? And yet the Russian synchro team should be banned? On what grounds?

Gymastics — where is “gymnastics” on that list? Answer: nowhere.

This is why — shortly after the release of Monday’s report — Bruno Grandi, president of FIG, the international gymnastics federation, put out a statement declaring that clean Russian gymnasts must be allowed to compete in Rio.

He said, ”The rights of every individual athlete must be respected. Participation at the Olympic Games is the highest goal of athletes who often sacrifice their entire youth to this aim. The right to participate at the Games cannot be stolen from an athlete, who has duly qualified and has not be found guilty of doping. Blanket bans have never been and will never be just."

Even McLaren himself, in the report, observes, at page 4, and “IP” in this context refers to McLaren, the “independent person” commissioned by WADA:

“The third paragraph of the IP’s mandate, identifying athletes who benefited from the manipulations, has not been the primary focus of the IP’s work. The IP investigative team has developed evidence identifying dozens of Russian athletes who appear to have been involved in doping. The compressed timeline of the IP investigation did not permit compilation of data to establish an antidoping rule violation. The time limitation required the IP to deem this part of the mandate of lesser priority. The IP concentrated on the other four directives of the mandate.”

Elsewhere, the report asserts, and repeatedly, that evidence rises to meet the law’s most demanding standard, that required for conviction of a criminal case in the United States, “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Here, a refresher basic: that is for a jury or a tribunal to decide, not the investigator.

Assume, though, that everything in the report is dead-bang true. It's easy to point a finger at "the Russians." It's a little different to say -- more, to prove -- that Igor, or Sasha, or Svetlana, or whoever had his or her sample swapped. Even if you can prove that, does that mean Igor or Sasha was doping? Did he or she know the sample was being swapped?

At page 87 of the report, McLaren notes, "The Moscow Laboratory personnel did not have a choice in whether to be involved in the State-directed system."

By the same logic, did athletes in this system have a "choice" in alleged use of illicit performance-enhancing substances? The report, page 49, details the concoction of a doping cocktail -- the Russians called it "the Duchess" -- that consisted of the steroids oral-turinabol, oxandrolone and methasterone. These were dissolved in alcohol -- Chivas for the men, vermouth for the women -- and swished around the mouth for ready absorption.

It doesn't take much imagination to conjure up a situation in which a Russian coach approaches Igor, Sasha, whoever with a glass of the Duchess and says, more or less, "This is your treatment." In such a situation, would an individual athlete feel he or she had the "choice" to say no?

For sure, whatever is in the system is an athlete's responsibility. This is a fundamental premise of the anti-doping rules. But the rules also now expressly acknowledge that intent to cheat -- or not -- matters, too.

As for further specifics that cut to the credibility of what's at issue:

McLaren “did not seek to interview persons living within the Russian Federation. This includes government officials,” page 8. So the report is deliberately one-sided?

“I am aware,” McLaren writes at page 21 in reference to the principle witness, Dr. Gregoriy Rodchenkov, the former director of the Moscow lab, “that there are allegations made against him by various persons and institutional representatives. While that might impinge on his credibility in a broader context, I do not find that it does so in respect of this report.”

Of course broader allegations might significantly impinge on Rodchenkov’s credibility. That’s another basic. Putin goes on for an entire paragraph in his statement about such allegations. Yet these assertions are not explored in any detail? Moreover, just to play common sense — how is it that Rodchenkov finds himself now in Los Angeles? From what source or sources might he have money to, you know, pay rent and buy dinner?

At page 25-6: “The compressed time frame in which to compile this Report has left much of the possible evidence unreviewed. This Report has skimmed the surface of the data that is available or could be available. As I write this Report our task is incomplete.” By definition, “incomplete” means exactly the opposite of “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Page 56, and a reference to the FSB, the Russian security service: “… it was not possible to fully determine the role of the FSB in sport and doping. The IP has only gained a glimpse into the FSB’s operations.” A “glimpse” does not make for proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

More of the same at page 59, referring to a specific FSB agent: “Were FSB [agent] Blokhin’s actions approved at the highest level of the FSB and the State? The IP cannot say.”

Without being able to say, there is a hole in this well-meaning report big enough to drive a truck through. About, oh, the size of the tunnel underneath the stadium in Rio from which the athletes enter for the opening ceremony.

See you there, Russian delegation. Behind your red, white and blue Russian flag.

Fat headlines are fun. A rush to judgment can feel so exhilarating. Yet serious decisions demand facts and measured judgment.

To believe the headlines, to take in the rush, one would believe that the World Anti-Doping Agency sat around for the better part of four years and did nothing amid explosive allegations of state-sponsored doping in Russia sparked in large measure by the whistleblower Vitaliy Stepanov, a former Russian doping control officer, and his wife, Yulia, a world-class middle-distance runner.

That’s just not true.

WADA, like any institution, can be faulted for many things. But in this instance, WADA officials did what they could when they could, and with a greater degree of sensitivity and attention to real-life consequence than the story that has dominated many mainstream media accounts and thus has started to take on a freight train-like run of its own.

“WADA’s foot-dragging has raised serious questions about the agency’s willingness to do its job,” Travis Tygart, the chief executive of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, wrote in a May 25 op-ed in the New York Times.

Tygart assuredly knows the rules perhaps better than anyone else. In a passage that curiously ignores the fact that WADA itself had no investigative authority until the very start of 2015, the op-ed also says: “WADA knew of the Stepanovs’ accusations for years; Mr. Stepanov was offering evidence of extensive doping in Russia since 2010. Yet the agency was moved to act only after the German documentary,” a December 2014 production on the channel ARD led by the journalist Hajo Seppelt. It was that documentary that broke the Russian scandal open.

An email that circulated this week from John Leonard, a leading U.S. swim coach, opened this way: “Did you see that WADA and Mr. Reedie knew about the entire Russian/ARD issue for 2.5 years before they finally told the whistleblowers to go to ARD?”

It added in a reference to Craig Reedie, the current WADA president, “Reedie is WADA chair and an [International Olympic Committee] VP, that explains the why they sat on it. Direct conflict of interest. He needs to go, now, from WADA.”

This expressly ignores three essential facts:

One, Reedie didn't take over as WADA president until January 2014. To ascribe responsibility to him for something that happened before that is patently unfair. How would he have known? Should have known?

Two, as anyone familiar with the Olympic scene knows well, interlocking directorates are a fact of life in the movement. Dick Pound, the long-term IOC member from Canada, served as WADA’s first president — and he is now, again, a champion to many for being outspoken on the matter of Russian doping after serving on a WADA-appointed independent commission that investigated the matter.

By definition, it can’t be a conflict of interest when there’s full disclosure that Reedie is both IOC vice president and WADA president. Moreover, to assert that Reedie would be acting in his role as WADA president with anything but the best intent assumes facts not in evidence.

Third, from the outset, as a report published last November from that WADA-appointed commission makes plain, the global anti-doping agency has been met in many quarters with considerable reluctance: “WADA continues to face a recalcitrant attitude on the part of many stakeholders that it is merely a service provider and not a regulator.”

WADA’s incoming director-general, Olivier Niggli, emphasized Friday in a telephone interview, referring to the Stepanovs, “We respect them for having been courageous.”

Niggli also said, “We are not the organization we are being portrayed as at the moment. It’s nothing against Vitaliy and his wife.” Amid a doping ban, Yulia Stepanova emerged as a star witness for that WADA-appointed commission.

“I understand,” Niggli said. “It’s not easy for them.”

Nothing right now in the anti-doping movement is easy. Perhaps that’s why, amid the storm sparked by the accusations of state-sanctioned doping, the time is right to take a step back and consider what might be done to make the anti-doping campaign that much more effective.

What’s at issue now is hardly solely of WADA’s doing. And none of this is new.

To be frank, it is — and always will be — part of human nature to want to cheat. The challenge in elite sport is how best to rein in that tendency.

In 2013, for instance, in the weeks and months leading up to the election that would see Reedie take over at the start of the next year as WADA president from the Australian government official John Fahey, all this was going down:

Revelations of teens in Turkey being doped. Allegations that West Germany’s government tolerated and covered up a culture of doping among its athletes for decades, and even encouraged it in the 1970s “under the guise of basic research.” Positive tests involving American and Jamaican track stars, including the leading sprinters Tyson Gay and Asafa Powell. And, of course, Lance Armstrong’s “confession” to Oprah Winfrey.

Was anyone then braying for the U.S. cycling team to be banned wholesale from the Olympics — which, it should be noted, was underwritten for years by the U.S. government’s Postal Service?

The distinction between the Turks then and the Russians now is — what? That Vladimir Putin is the Russian president?

The Russian allegations are extremely serious. But for the moment, they are just that — allegations, without conclusive, adjudicated proof.

WADA, created as a collaboration between sport and governments, is now roughly 17 years old. Without government buy-in of some sort, the whole thing would probably collapse and yet there’s a delicate balance when it comes to the risk of government interference. Why? In virtually every country except for the United States, responsibility — and funding — for Olympic sport falls to a federal ministry.

WADA’s annual budget is roughly $26 million.

This number, $26 million, forms the crux of the challenge. Most everyone says they want clean sport, particularly in the Olympic context. But do they, really?

Niggli said, “People need to understand the expectation put on us. If they want us to deliver, that is going to take more resources.”

Context, too. An athlete who can pass even hundreds of tests is not necessarily clean, despite the public tendency to want to believe that a negative test result means an athlete is positively clean. Ask Armstrong. Or Marion Jones.

Referring to widespread perceptions of the anti-doping campaign, Pound said in an interview this week, "If you were to ask me that about the NFL or Major League Baseball … I would say they don’t really care. These are professional entertainers. If people are suspended for 80 games or whatever, nobody really cares.”

Indeed, three players — the major leaguers Daniel Stumpf of the Phillies and Chris Colabello of the Blue Jays and the minor leaguer Kameron Loe — were recently suspended for taking the anabolic steroid turinabol, the blue pill at the core of the East German doping program in the 1970s.

Has that, compared to the saga of the Russians, dominated the headlines? Hardly.

Pound continued: “But you watch each time there’s a positive test in the Olympics. That affects people. They kind of hope the Olympics are a microcosm of the world and if the Olympics can work, then maybe the world can work.

“If something goes wrong at the Olympics, there’s inordinate disappointment. If that happens too often, it will turn people off.”

At the same time, when it’s time to put up or shut up — is there genuinely political and financial will across the world to make Pound’s words meaningful?

Maria Sharapova, the Russian tennis star busted for the heart-drug meldonium, herself has enjoyed annual revenues more than than WADA’s $26 million per-year budget. Forbes says Sharapova, the world’s highest-paid female athlete for the 11th straight year, made $29.7 million between June 2014 and June 2015.

Big-time U.S. college athletic department budgets can run to five, six or more times WADA’s $26 million. Texas A&M’s revenue, according to a USA Today survey: $192 million. The ranks of those whose annual revenues total roughly $26 million: Illinois State and Toledo.

Down Under, in a long-running saga, 34 past and present Australian Football League players have been banned for doping. Just last week, the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority, which in 2014 initiated action against the players, confirmed its budget was being cut by 20 percent. In fiscal year 2014, ASADA boasted a staff of 78. By 2017, that figure will be 50, the cuts affecting “all of ASADA’s functions, including our testing, investigative, education and administrative units,” the agency told the Australian broadcast outlet ABC.

The World Anti-Doping Code took effect in 2004. After lengthy consultations, a revised Code came into being in 2009. A further-revised version took effect, again after considerable discussion, in January 2015.

Per its new rules, it was only then — January 2015 — that WADA finally obtained the authority to run investigations.

But even that authority is necessarily limited.

Critically, WADA does not still — cannot — have subpoena power, meaning the authority under threat of sanction to compel testimony or evidence.

Moreover: who is going to pay for any and all investigations?

Suggestions have been advanced that perhaps a fraction of the billions in Olympic-related broadcast fees paid to the IOC ought to go to WADA. Or leading pharmaceutical companies or top-tier Olympic sponsors not only could but should contribute significantly as a matter of corporate social responsibility.

All this remains to be hashed out.

Meanwhile, it is without dispute that any meaningful investigation takes time, resource, patience, planning and, in the best cases, sound reasoning.

As Niggli put it, “The message is that these investigations — this is one example — take time. If you want to get something, you can’t react emotionally and throw everything out. In this case that would have been the end of the story.”

Stepanov first approached WADA officials at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver.

“It’s not that in 2010 Vitaliy came to us with a file, a binder, and said, ‘This is what is happening in Russia,’ and we sat on that,” Niggli said.

“At first he came to us and said he had some worries about what was going on. He maybe had some information from his job and potentially some information from his wife.

“This was a conversation for a number of years.”

In 2010, Niggli said, there were “two emails exchanged,” the substance of both was, more or less, let’s meet again and find a way to communicate. In 2011, there was another meeting, in Boston — the thinking that a get-together would hardly attract attention because Stepanov was there to run the marathon. In 2012, more emails. “All this time,” Niggli said, Stepanov had “not told his wife he was talking to us.”

Why? “She was competing and doping, as we now know. He was worried about her and protecting her.”

Niggli also said of the period from 2010 to 2013: “That was not at all a stage where we had corroborating evidence.”

The “game-changer,” as Niggli put it, came when Yulia Stepanova was busted for doping, formally announced in February 2013: “They together decided they would do the right thing.”

It was about this time that, according to the WADA-appointed independent commission, Stepanova started making secret recordings with Russian coaches and officials. The recordings would carry on through November 2014; she made them at places as varied as Moscow’s Kazinsky rail station and a hotel in Kyrgyzstan, a former Soviet satellite.

On Feb. 10, 2013, Stepanov sent an email to a WADA contact. It read, in part:

“After thinking for another few hours and talking to my wife, to try to make a bigger impact we need more evidence. We will not hide anything from you … it’s not really my wife’s fault she is being punished but we feel we can get more evidence. To get more evidence we need more time.”

Two days later, another Stepanov email: “I spoke to my wife and here is what we think right now … we think right now that probably there is no reason to really rush everything.”

The next month, WADA organized another meeting — the Stepanovs and Jack Robertson, a former U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration officer who was hired in 2011 as WADA’s chief investigative officer (the argument: the agency pro-actively trying to make advancements though it then had no authority to conduct its own investigations).

Robertson was “very careful to make sure this was confidential, to make sure they would not be put in danger,” Niggli said.

“Obviously, we would not want to share [what it might be learning] with Russia. We did not share with the IAAF,” track and field’s international governing body, “which now looks like a good and prudent decision,” given that then-IAAF president Lamine Diack is alleged to have orchestrated a conspiracy that took more than $1 million in bribes to keep Russian athletes eligible, including at the London 2012 Olympics.

In 2013, WADA went to the Moscow anti-doping lab, hoping to find corroborating evidence. “We found some but not as much as we hoped to,” Niggli said. The agency opened a “disciplinary commission” and for some months it remained uncertain if the Russians would keep the lab, and the Sochi 2014 Winter Games satellite, accredited.

“With the information we had,” Niggli said, “we asked whether this was not putting the whistle-blowers,” the Stepanovs, “in danger.”

The Stepanovs, along with their young son, are now out of Russia, in an undisclosed location.

It was in early 2014 that Robertson sent an email to Stepanov suggesting he get in touch with Seppelt, the German reporter and filmmaker.

The ARD broadcast aired that December.

Just a few weeks later, at the start of 2015, WADA, with investigative authority, commissioned the three-member independent panel: Canadian law professor Richard McLaren, German law enforcement official Günter Younger and Pound.

“That is the big picture,” Niggli said. “It’s not something that happened on Day One. It built over time. It was long work. It was done the right way, to protect [the Stepanovs] and make sure they would not lose the benefit of all that has been done.

He added a moment later, “I’m sure that if we had acted earlier, there would be no result. It would have been dimmed or killed. It would have been Vitaliy and his wife alone, with the denial of a state such as Russia. That,” he said, “would not have held much weight.”