Fat headlines are fun. A rush to judgment can feel so exhilarating. Yet serious decisions demand facts and measured judgment.

To believe the headlines, to take in the rush, one would believe that the World Anti-Doping Agency sat around for the better part of four years and did nothing amid explosive allegations of state-sponsored doping in Russia sparked in large measure by the whistleblower Vitaliy Stepanov, a former Russian doping control officer, and his wife, Yulia, a world-class middle-distance runner.

That’s just not true.

WADA, like any institution, can be faulted for many things. But in this instance, WADA officials did what they could when they could, and with a greater degree of sensitivity and attention to real-life consequence than the story that has dominated many mainstream media accounts and thus has started to take on a freight train-like run of its own.

“WADA’s foot-dragging has raised serious questions about the agency’s willingness to do its job,” Travis Tygart, the chief executive of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, wrote in a May 25 op-ed in the New York Times.

Tygart assuredly knows the rules perhaps better than anyone else. In a passage that curiously ignores the fact that WADA itself had no investigative authority until the very start of 2015, the op-ed also says: “WADA knew of the Stepanovs’ accusations for years; Mr. Stepanov was offering evidence of extensive doping in Russia since 2010. Yet the agency was moved to act only after the German documentary,” a December 2014 production on the channel ARD led by the journalist Hajo Seppelt. It was that documentary that broke the Russian scandal open.

An email that circulated this week from John Leonard, a leading U.S. swim coach, opened this way: “Did you see that WADA and Mr. Reedie knew about the entire Russian/ARD issue for 2.5 years before they finally told the whistleblowers to go to ARD?”

It added in a reference to Craig Reedie, the current WADA president, “Reedie is WADA chair and an [International Olympic Committee] VP, that explains the why they sat on it. Direct conflict of interest. He needs to go, now, from WADA.”

This expressly ignores three essential facts:

One, Reedie didn't take over as WADA president until January 2014. To ascribe responsibility to him for something that happened before that is patently unfair. How would he have known? Should have known?

Two, as anyone familiar with the Olympic scene knows well, interlocking directorates are a fact of life in the movement. Dick Pound, the long-term IOC member from Canada, served as WADA’s first president — and he is now, again, a champion to many for being outspoken on the matter of Russian doping after serving on a WADA-appointed independent commission that investigated the matter.

By definition, it can’t be a conflict of interest when there’s full disclosure that Reedie is both IOC vice president and WADA president. Moreover, to assert that Reedie would be acting in his role as WADA president with anything but the best intent assumes facts not in evidence.

Third, from the outset, as a report published last November from that WADA-appointed commission makes plain, the global anti-doping agency has been met in many quarters with considerable reluctance: “WADA continues to face a recalcitrant attitude on the part of many stakeholders that it is merely a service provider and not a regulator.”

WADA’s incoming director-general, Olivier Niggli, emphasized Friday in a telephone interview, referring to the Stepanovs, “We respect them for having been courageous.”

Niggli also said, “We are not the organization we are being portrayed as at the moment. It’s nothing against Vitaliy and his wife.” Amid a doping ban, Yulia Stepanova emerged as a star witness for that WADA-appointed commission.

“I understand,” Niggli said. “It’s not easy for them.”

Nothing right now in the anti-doping movement is easy. Perhaps that’s why, amid the storm sparked by the accusations of state-sanctioned doping, the time is right to take a step back and consider what might be done to make the anti-doping campaign that much more effective.

What’s at issue now is hardly solely of WADA’s doing. And none of this is new.

To be frank, it is — and always will be — part of human nature to want to cheat. The challenge in elite sport is how best to rein in that tendency.

In 2013, for instance, in the weeks and months leading up to the election that would see Reedie take over at the start of the next year as WADA president from the Australian government official John Fahey, all this was going down:

Revelations of teens in Turkey being doped. Allegations that West Germany’s government tolerated and covered up a culture of doping among its athletes for decades, and even encouraged it in the 1970s “under the guise of basic research.” Positive tests involving American and Jamaican track stars, including the leading sprinters Tyson Gay and Asafa Powell. And, of course, Lance Armstrong’s “confession” to Oprah Winfrey.

Was anyone then braying for the U.S. cycling team to be banned wholesale from the Olympics — which, it should be noted, was underwritten for years by the U.S. government’s Postal Service?

The distinction between the Turks then and the Russians now is — what? That Vladimir Putin is the Russian president?

The Russian allegations are extremely serious. But for the moment, they are just that — allegations, without conclusive, adjudicated proof.

WADA, created as a collaboration between sport and governments, is now roughly 17 years old. Without government buy-in of some sort, the whole thing would probably collapse and yet there’s a delicate balance when it comes to the risk of government interference. Why? In virtually every country except for the United States, responsibility — and funding — for Olympic sport falls to a federal ministry.

WADA’s annual budget is roughly $26 million.

This number, $26 million, forms the crux of the challenge. Most everyone says they want clean sport, particularly in the Olympic context. But do they, really?

Niggli said, “People need to understand the expectation put on us. If they want us to deliver, that is going to take more resources.”

Context, too. An athlete who can pass even hundreds of tests is not necessarily clean, despite the public tendency to want to believe that a negative test result means an athlete is positively clean. Ask Armstrong. Or Marion Jones.

Referring to widespread perceptions of the anti-doping campaign, Pound said in an interview this week, "If you were to ask me that about the NFL or Major League Baseball … I would say they don’t really care. These are professional entertainers. If people are suspended for 80 games or whatever, nobody really cares.”

Indeed, three players — the major leaguers Daniel Stumpf of the Phillies and Chris Colabello of the Blue Jays and the minor leaguer Kameron Loe — were recently suspended for taking the anabolic steroid turinabol, the blue pill at the core of the East German doping program in the 1970s.

Has that, compared to the saga of the Russians, dominated the headlines? Hardly.

Pound continued: “But you watch each time there’s a positive test in the Olympics. That affects people. They kind of hope the Olympics are a microcosm of the world and if the Olympics can work, then maybe the world can work.

“If something goes wrong at the Olympics, there’s inordinate disappointment. If that happens too often, it will turn people off.”

At the same time, when it’s time to put up or shut up — is there genuinely political and financial will across the world to make Pound’s words meaningful?

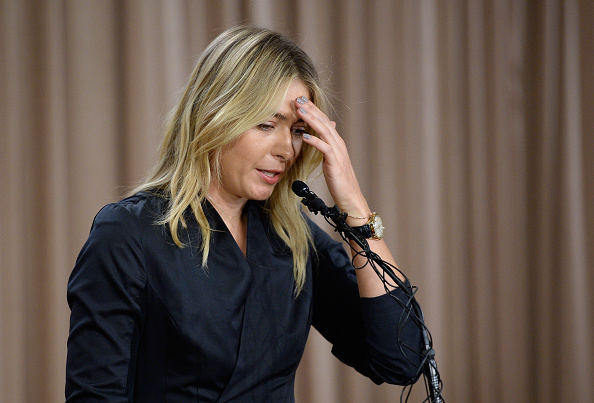

Maria Sharapova, the Russian tennis star busted for the heart-drug meldonium, herself has enjoyed annual revenues more than than WADA’s $26 million per-year budget. Forbes says Sharapova, the world’s highest-paid female athlete for the 11th straight year, made $29.7 million between June 2014 and June 2015.

Big-time U.S. college athletic department budgets can run to five, six or more times WADA’s $26 million. Texas A&M’s revenue, according to a USA Today survey: $192 million. The ranks of those whose annual revenues total roughly $26 million: Illinois State and Toledo.

Down Under, in a long-running saga, 34 past and present Australian Football League players have been banned for doping. Just last week, the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority, which in 2014 initiated action against the players, confirmed its budget was being cut by 20 percent. In fiscal year 2014, ASADA boasted a staff of 78. By 2017, that figure will be 50, the cuts affecting “all of ASADA’s functions, including our testing, investigative, education and administrative units,” the agency told the Australian broadcast outlet ABC.

The World Anti-Doping Code took effect in 2004. After lengthy consultations, a revised Code came into being in 2009. A further-revised version took effect, again after considerable discussion, in January 2015.

Per its new rules, it was only then — January 2015 — that WADA finally obtained the authority to run investigations.

But even that authority is necessarily limited.

Critically, WADA does not still — cannot — have subpoena power, meaning the authority under threat of sanction to compel testimony or evidence.

Moreover: who is going to pay for any and all investigations?

Suggestions have been advanced that perhaps a fraction of the billions in Olympic-related broadcast fees paid to the IOC ought to go to WADA. Or leading pharmaceutical companies or top-tier Olympic sponsors not only could but should contribute significantly as a matter of corporate social responsibility.

All this remains to be hashed out.

Meanwhile, it is without dispute that any meaningful investigation takes time, resource, patience, planning and, in the best cases, sound reasoning.

As Niggli put it, “The message is that these investigations — this is one example — take time. If you want to get something, you can’t react emotionally and throw everything out. In this case that would have been the end of the story.”

Stepanov first approached WADA officials at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver.

“It’s not that in 2010 Vitaliy came to us with a file, a binder, and said, ‘This is what is happening in Russia,’ and we sat on that,” Niggli said.

“At first he came to us and said he had some worries about what was going on. He maybe had some information from his job and potentially some information from his wife.

“This was a conversation for a number of years.”

In 2010, Niggli said, there were “two emails exchanged,” the substance of both was, more or less, let’s meet again and find a way to communicate. In 2011, there was another meeting, in Boston — the thinking that a get-together would hardly attract attention because Stepanov was there to run the marathon. In 2012, more emails. “All this time,” Niggli said, Stepanov had “not told his wife he was talking to us.”

Why? “She was competing and doping, as we now know. He was worried about her and protecting her.”

Niggli also said of the period from 2010 to 2013: “That was not at all a stage where we had corroborating evidence.”

The “game-changer,” as Niggli put it, came when Yulia Stepanova was busted for doping, formally announced in February 2013: “They together decided they would do the right thing.”

It was about this time that, according to the WADA-appointed independent commission, Stepanova started making secret recordings with Russian coaches and officials. The recordings would carry on through November 2014; she made them at places as varied as Moscow’s Kazinsky rail station and a hotel in Kyrgyzstan, a former Soviet satellite.

On Feb. 10, 2013, Stepanov sent an email to a WADA contact. It read, in part:

“After thinking for another few hours and talking to my wife, to try to make a bigger impact we need more evidence. We will not hide anything from you … it’s not really my wife’s fault she is being punished but we feel we can get more evidence. To get more evidence we need more time.”

Two days later, another Stepanov email: “I spoke to my wife and here is what we think right now … we think right now that probably there is no reason to really rush everything.”

The next month, WADA organized another meeting — the Stepanovs and Jack Robertson, a former U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration officer who was hired in 2011 as WADA’s chief investigative officer (the argument: the agency pro-actively trying to make advancements though it then had no authority to conduct its own investigations).

Robertson was “very careful to make sure this was confidential, to make sure they would not be put in danger,” Niggli said.

“Obviously, we would not want to share [what it might be learning] with Russia. We did not share with the IAAF,” track and field’s international governing body, “which now looks like a good and prudent decision,” given that then-IAAF president Lamine Diack is alleged to have orchestrated a conspiracy that took more than $1 million in bribes to keep Russian athletes eligible, including at the London 2012 Olympics.

In 2013, WADA went to the Moscow anti-doping lab, hoping to find corroborating evidence. “We found some but not as much as we hoped to,” Niggli said. The agency opened a “disciplinary commission” and for some months it remained uncertain if the Russians would keep the lab, and the Sochi 2014 Winter Games satellite, accredited.

“With the information we had,” Niggli said, “we asked whether this was not putting the whistle-blowers,” the Stepanovs, “in danger.”

The Stepanovs, along with their young son, are now out of Russia, in an undisclosed location.

It was in early 2014 that Robertson sent an email to Stepanov suggesting he get in touch with Seppelt, the German reporter and filmmaker.

The ARD broadcast aired that December.

Just a few weeks later, at the start of 2015, WADA, with investigative authority, commissioned the three-member independent panel: Canadian law professor Richard McLaren, German law enforcement official Günter Younger and Pound.

“That is the big picture,” Niggli said. “It’s not something that happened on Day One. It built over time. It was long work. It was done the right way, to protect [the Stepanovs] and make sure they would not lose the benefit of all that has been done.

He added a moment later, “I’m sure that if we had acted earlier, there would be no result. It would have been dimmed or killed. It would have been Vitaliy and his wife alone, with the denial of a state such as Russia. That,” he said, “would not have held much weight.”