EUGENE — As Sunday’s final-day action at historic Hayward Field got underway, the crowd was told — this is the mantra of the 2016 Trials — that the U.S. Olympic track and field team is “the hardest team to make.” It’s not. The swim team is way harder. But more on that in a moment.

What is indisputably true: the 10-day run of the Trials is a study in emotion. One, two or three in Eugene is typically cause for joy. What, though, about four, five or farther down?

Amid all the celebrating, and there was plenty of it Sunday with nine finals that saw the likes of teenager Sydney McLaughlin (third place, women’s 400 hurdles, first 16-year-old on the U.S. team in 40 years) and 21-year-old Byron Robinson (second, men’s 400 hurdles) secure Rio spots, the real story of the Trials is, and always will be, disappointment.

And how to handle it.

Track and field’s global governing body, the International Assn. of Athletics Federations, had reconfigured the Rio 2016 schedule so that Allyson Felix could try for the 200-400 double. Here, Felix won the 400. On Sunday, though, she finished fourth in the 200, one-hundredth of a second out.

“Honestly, I’m disappointed,” Felix said. “All year I planned for this race, and for it to end here, it’s disappointing. But when I look back and see everything that happened,” in particular an ankle injury this spring, “I still think it’s quite amazing that I was able to make this team. I feel like everything was against me.”

The tension and drama of the Trials makes for a once-evey-four-years study in how to handle what life gives you — or throws at you.

As Jenny Simpson, the Daegu 2011 world championship gold medalist who on Sunday won a ferocious women’s 1500 in 4:04.74, put it, “On the starting line, you have that balance of confidence and doubt,” adding that track and field is, and has to be, a "really selfish sport — it’s you against the world.”

She added, “The selection process makes you go through the fire,” adding in a reference to the Trials, “The gift we get from this really horrible and brutal experience is that when we get to the Games we have a sense we have done something difficult already and we are prepared.”

Erik Kynard, the 2012 Trials runner-up in the high jump, went to London and won silver. Here Sunday, he won the 2016 Trials. Asked what he learned from 2012, he said, with a laugh, “Jump higher.”

Robinson, after the 400 hurdles, “I’m shellshocked. I’m overcome with joy.” He also said, “I just wanted a chance, you know?”

Generally speaking, top-three at the track and field Trials go to the Games. Everyone else stays home.

With all due respect to Charles Barkley, and his assertion that sports stars are not role models — sorry, they are. That’s the case all the more in track and field; participation in track and field in high school and college remains robust.

“Knowing we’re doing it right, knowing we’re doing it the right way — hopefully we’re inspiring young women,” said Shannon Rowbury, the Berlin 2009 worlds bronze medalist who took second in Sunday’s women’s 1500 in 4:05.39.

Math makes plain that roughly nine of 10 of those who showed up here to compete in Eugene will not be heading to Rio. But it’s even harder to make the U.S. swim team.

Some numbers:

The swim Trials, in Omaha this month, held 52 spots. In swimming, moreover, qualifying is, again speaking generally, not top-three; it’s top two.

Because of doubles or even triples — the likes of Michael Phelps, Katie Ledecky and Maya DiRado will each compete in multiple events in Rio — the field of 52 going to Rio will actually be 45.

That’s out of 1,737 entries, according to USA Swimming.

Math: 2.5 percent of those in Omaha are heading to Rio.

In track and field, there are 141 spots, including relays.

Not all spots get filled because Americans will not have met qualifying standards set by track’s global governing body, the International Assn. of Athletics Federations.

By meet’s end, per USA Track & Field, there were 1,077 declared entries, 879 individual athletes.

To make the math as apples-to-apples as possible, and acknowledging that 141 is a loose number — 141 over 1,077 is 13.1 percent.

When you’re part of that magical 13 percent, it’s easy.

“I couldn’t ask for more,” Tori Bowie, the women’s 200-meter winner, said after Sunday’s racing. She took third in the 100, and now gets to double in Rio.

“I can’t believe this is happening right now,” the teenager McLaughlin said, adding a moment later, “My mind was on finishing the race and eating a cheeseburger.”

When you’re not?

Compare and contrast:

In the women’s 800 last Monday, Alysia Montaño fell on the final backstretch. She wailed. She fell to her knees. She cried.

This made for great TV.

At the same time, if a junior-high or high school athlete did this, what would the likely reaction be from his or her coach?

Meeting the press after with 2-year-old daughter, Linnea, in tow, Montaño said, “This is it, you know. You get up and you’re, like, really far away and your heart breaks.”

From there, it turned into something akin to a therapy session, Montaño saying her “biggest struggle this year” had been “finding peace and why I’m even trying for an Olympic team,” calling it all that “emotional baggage.”

Montaño was justifiably lauded two years ago when, 34 weeks pregnant, she ran the 800 at the U.S. national championships — a role model, for sure, on many levels.

Here?

“Eight years of my life as a professional runner, my entire professional career, has been a farce, basically,” she said. “Now everyone’s talking about the Russians not running in the Olympics but they’re missing the point. The IAAF is a corrupt institution that is still running the Games.”

It wasn’t until a day later that Montaño — who is active on social media and says her fans help her “pick up the pieces” — filed this to Twitter, congratulating Kate Grace, Ajee’ Wilson and Chrishuna Williams, who finished 1-2-3 in the race:

https://twitter.com/AlysiaMontano/status/750476446796124160

The sequence that sent Monaño to the track also took out Brenda Martinez. She won bronze at the 2013 Moscow worlds in the 800.

Martinez would say after the 2016 Trials 800, “I felt great but I got clipped from behind. That’s track and field. I’ve got to get ready for the 1500. Some days it doesn’t go your way. Today it was me.”

Instant-karma department: on Sunday, Martinez got third in the 1500, by three-hundredths of a second, finishing in 4:06.16. She got there with a finish-line dive.

“However people want to take it,” Martinez said. “I feel like it had to happen for a reason. That’s the way I believe life works, you know: you’re going to get tested. If people can see what I went through, then maybe they won’t doubt themselves the next time something happens to them.”

Make no mistake: Martinez’s third was very popular, with the crowd, with Rowbury and Simpson and with many others.

Simpson made a point of saying she had reached out after the 800 to Martinez. And for all that there is in, and justifiably, in being “selfish,” Simpson said, “I went to the starting line with a little bit more love … and a litttle bit less selfishness than in the past.”

Emma Coburn, the steeplechase winner here, posted to Twitter:

https://twitter.com/emmajcoburn/status/752293842729054208

In London four years ago, Leo Manzano won silver in the men’s 1500. He was the first American to medal in the 1500 since Jim Ryun in 1968.

On Sunday in the rain, Manzano, battling Ben Blankenship for the third and final spot in the 1500, reached for a gear he had often found before. It wasn’t there. Manzano took fourth, in 3:36.62 — not even half a second behind Blankenship, 3:36.18.

Matthew Centrowitz won the race, and easily, in 3:34.09. Robby Andrews got second, 3:34.88.

The race proved the fastest Trials 1500 ever, Centrowitz breaking Steve Scott’s 1980 Trials mark, 3:35.15, and the top-four putting down the Trials’ quickest top-four times.

In the London 1500, Centrowitz took fourth. “I'm ready for whatever they throw at me in Rio,” he said Sunday. “If it’s a 3:33 race, I’m ready for that.”

Manzano: “I wish the result had been different. Unfortuantely, it’s not. You’ve got to face the facts, and congratulte your teammates. They fought hard today. It wasn’t my day today.”

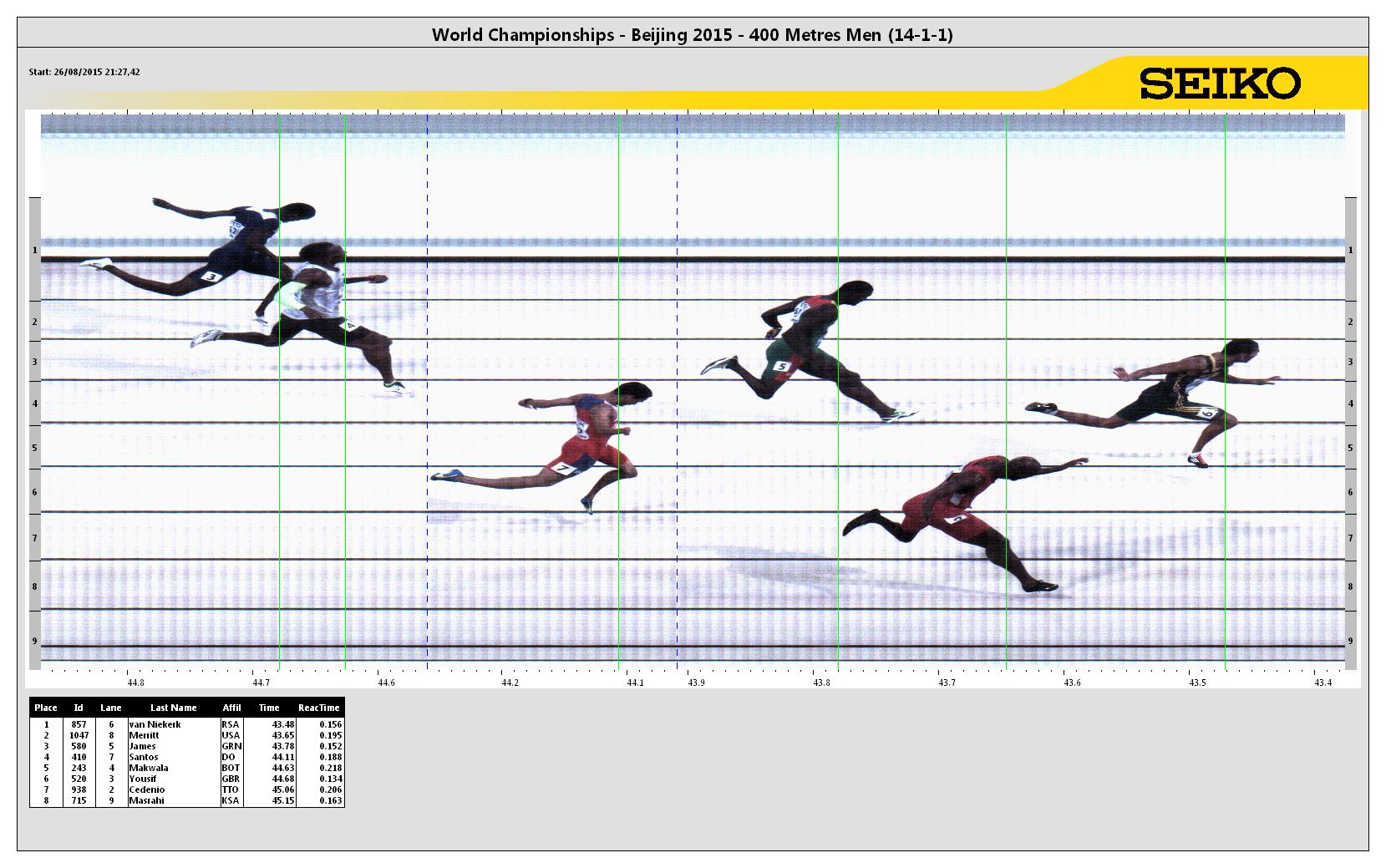

In the men’s 110-meter hurdles, Aries Merritt won bronze at last year’s world championships in Beijing, running on kidneys that were so bad he underwent a transplant — his sister the donor. Merritt is the 2012 London gold medalist and, as well, the world record holder in the event, 12.8.

In Saturday’s 110 hurdle final, Merritt finished fourth — like Felix in the 200, exactly one-hundredth away from third. He crossed in 13.22 seconds. Jeff Porter and Ronnie Ash went 3-2, both in 13.21; University of Oregon star Devon Allen ran away with the event, 13.03.

Merritt afterward: “Given the circumstances, I did the best I could with what I had and I came up a little bit short. I’ve come to grips with it. But it couldn’t be worse than being told you’ll never run again. I’ve been to the Olympics, I’ve won the Olympic Games, I’ve broken the world record. I mean, someone else can have a turn.”

In that same race, Jason Richardson finished fifth, in 13.28. He is the London silver medalist and the Daegu 2011 world champion.

His reaction:

https://twitter.com/JaiRich/status/751951488054808576

Jillian Camarena-Williams, a two-time Olympian, is 34. She and her husband, Dustin, 38, who will be the head trainer for the U.S. track team in Rio, married after the Berlin 2009 world championships. They moved to Tucson after the 2011 worlds. Their daughter, Miley, was born on the very day of the women’s shot put event at the 2014 championships in Sacramento.

“Our relationship is all about track meets,” she said, laughing.

The thing is — it’s not.

Camarena-Williams herniated her back at the London Games. She needed surgery. Then she had to decide — should I try to come back? If so, why?

The answers:

“I missed the sport and the people that are in it, the people that have helped me throughout my career,” she said in a quiet moment Sunday.

She also talked about what she called “my journey.”

Track brought her a husband and now a family: "It’s more about the places we were able to go, people we were able to meet than the outcome. I have talked to young people and brought my medals,” including a third in Daegu in 2011, the first medal of any kind for an American woman in the shot in the history of the track worlds.

“I love these medals. They represent that journey to me. But they just sit in my drawer. They don’t hang in our house. We’re porud of them. But we’re way more exicted about the things we were able to do along the way than the actual hardware.”

After the third throw — of six — here, in the rain, Camarena-Wiilliams stood third. But she knew it wouldn’t be enough.

Heading out for her final throw, in round six, Camarena-Williams’ sister, 36-year-old sister, Christi, a nurse in Sacramento, told her, “Just smile. Go out there and enjoy yourself.”

Michelle Carter, on her sixth and final throw, won, in 19.59 meters, 64 feet, 3-1/4 inches. Raven Saunders and Felisha Johnson finished 2-3. Camarena-Williams ended at 18.81, 61 8-1/2.

A lot of family was here in Eugene for Jillian and Dustin. Her mother. Two of her three siblings. A cousin with her two daughters. His brother. Two sets of his aunts and uncles.

Coaches.

And, of course, 2-year-old Miley.

“It’s a village that supports us to get [to the Olympics] in the first place,” Rowbury would observe. “It’s a commitment to trying to be the best you can be, a commitment to the people who support you along the way and a commitment to honor your country.”

"No matter what I do in life," Robinson said, "if the people back home aren’t proud of me I know that I didn’t really live up to expectations. Knowing that they are behind me, I know I can achieve anything."

After Jillian Camarena-Williams' final throw, no tears. She went looking for her husband and their daughter.

“Sometimes,” she said Sunday, holding the baby, “you are overtaken with emotion. So much can happen. I feel like I’m in a really good place with our family and where we’re at. It was disappointing, but I have to put a smile on my face and be grateful for what we have, outside the track.

“And we have a lot.”