BEIJING — Coming into these 2015 track and field world championships, it looked for — and to — all the world like this could be the meet when the American team finally reached that elusive 30-total medal count.

With the meet now at its (just-past) halfway point, that looks exceedingly unlikely. The question now is more fundamental: is this 2015 performance a blip or a precursor for next year’s Rio 2016 Summer Games and, indeed, beyond?

Coming into Wednesday, four nights into the nine-day meet, the United States had exactly as many golds as Canada: one.

The American Joe Kovacs won the men’s shot put; the Canadian Shawn Barber, the men’s pole vault.

After Wednesday, the United States still had -- one.

The Brits? Three. The Americans' new political friends in Cuba? Two.

Overall, Kenya led the medal count, with 11, six gold; the Americans were next, with nine (that one gold, three silver, five bronze).

Kenya is not just marathoners anymore. Julius Yego won the men's javelin Wednesday night with the farthest throw in 14 years, 92.72 meters, or 304 feet, 2 inches.

Meanwhile, the IAAF announced earlier in the evening that two Kenyans, Francisca Koki and Joyce Zakari, had tested positive after providing samples on August 20 and 21, respectively — that is, immediately before the meet started. These “targeted tests were conducted by the IAAF at the athlete hotels,” the federation said in a statement. No other details were immediately available.

The run-up to the 2015 championships has been marked by waves of media reports alleging doping positives and cover-ups in the Kenyan track and field scene.

Zakari had run second in her 400 heat in 50.71, then proved a no-show for the first of Tuesday’s three semifinals.

Koki, in the 400 hurdles, ran 58.96 in her opening round, second-slowest in the entire field.

For the U.S. to prevail in the medals count next year at Rio, as it did in London 2012, with 103, China next at 88, the weight rests on its track and swim teams.

In London, the swim team won 30 medals at the pool, 31 including Haley Anderson’s silver in the open-water competition. The track team: 29.

A few weeks ago at the 2015 world swim championships in Kazan, Russia, the U.S. team ended up with 23 medals, eight gold. That’s arguably misleading, though, because two of those medals came in the mixed relays, which would be new Olympic events. So: 21.

Of course, Michael Phelps did not swim in Kazan and threw down three world-best performances that same week at the U.S. nationals. Even so, it was arguably the American team’s poorest performance at a worlds dating to 1973; in 1994, the Americans went home from Rome with 21 medals, four gold.

For the track team, expectations had soared before this meet in Beijing, the U.S. sending arguably its deepest team ever.

To be sure, the Americans have had some successes. In the women’s 10,000 meters, for example, U.S. runners went 3-4-6, Emily Infeld passing Molly Huddle at the line for the bronze, Shalane Flanagan taking sixth.

Shamier Little, with a bright green bow in her hair, and Cassandra Tate went 2-3 Wednesday night in the women's 400 hurdles. Zuzana Hejnova of the Czech Republic, the Moscow 2013 champion who had spent most of 2014 recovering from a broken bone in her left foot, dominated again in a 2015 world best 53.50. Little ran 53.94, Tate 54.02.

The final events Wednesday night, however, proved hugely emblematic of American performance:

Only one American, Justin Gatlin, had even made it through the heats to the semifinals of the men’s 200. He ran an easy 19.87 to move on to the finals, that 19.87 the second-fastest semifinal time ever at a worlds; Francis Obikwelu ran 19.84 in 1999.

Justin Gatlin's 19.87 in the men's 200m semi tonight was the second-fastest semifinal time ever at the World Championships. The fastest: Nigeria's Francis Obikwelu's 19.84, in 1999.

In the next heat, Usain Bolt, who defeated Gatlin in the 100 Sunday night by one-hundredth of a second, ran a season-best 19.95, chatting with South Africa's Anaso Jobodwana in the next lane, second in 20.01, as they crossed the line.

In the women's pole vault, American Jenn Suhr, the 2012 Olympic champion, afforded a huge opportunity because Russia's Yelena Isinbayeva was not jumping (the all-time pole vault diva gave birth last June to a daughter), managed a tie for fourth, at 4.70 meters, or 15 feet, 5 inches -- along with another American, Sandi Morris, a rising college star, and Sweden's Angelica Bengtsson.

Cuba's Yarisley Silva won, with 4.90, or 16-0 3/4. Brazil's Fabiana Murer took second, at 4.85, 15-11. Greece's Nikoleta Kyriakopoulo got third, at 4.80, 15-9.

Silva made three attempts at 5.01, 16-5, but did not clear. Isinbayeva holds the world record, 5.06, 16-7, set six years ago.

Emma Coburn had been a medal hope in the women's 3000 steeplechase. She finished fifth, in 9:21.78. Hyvin Kiyeng Jepkemoi of -- where else? -- Kenya took gold, in 9:19.11. Habiba Shribi of Tunisia came second, 13-hundredths back, Gesa Felicitas Krause of Germany in a personal-best 9:19.25, 14-hundredths behind.

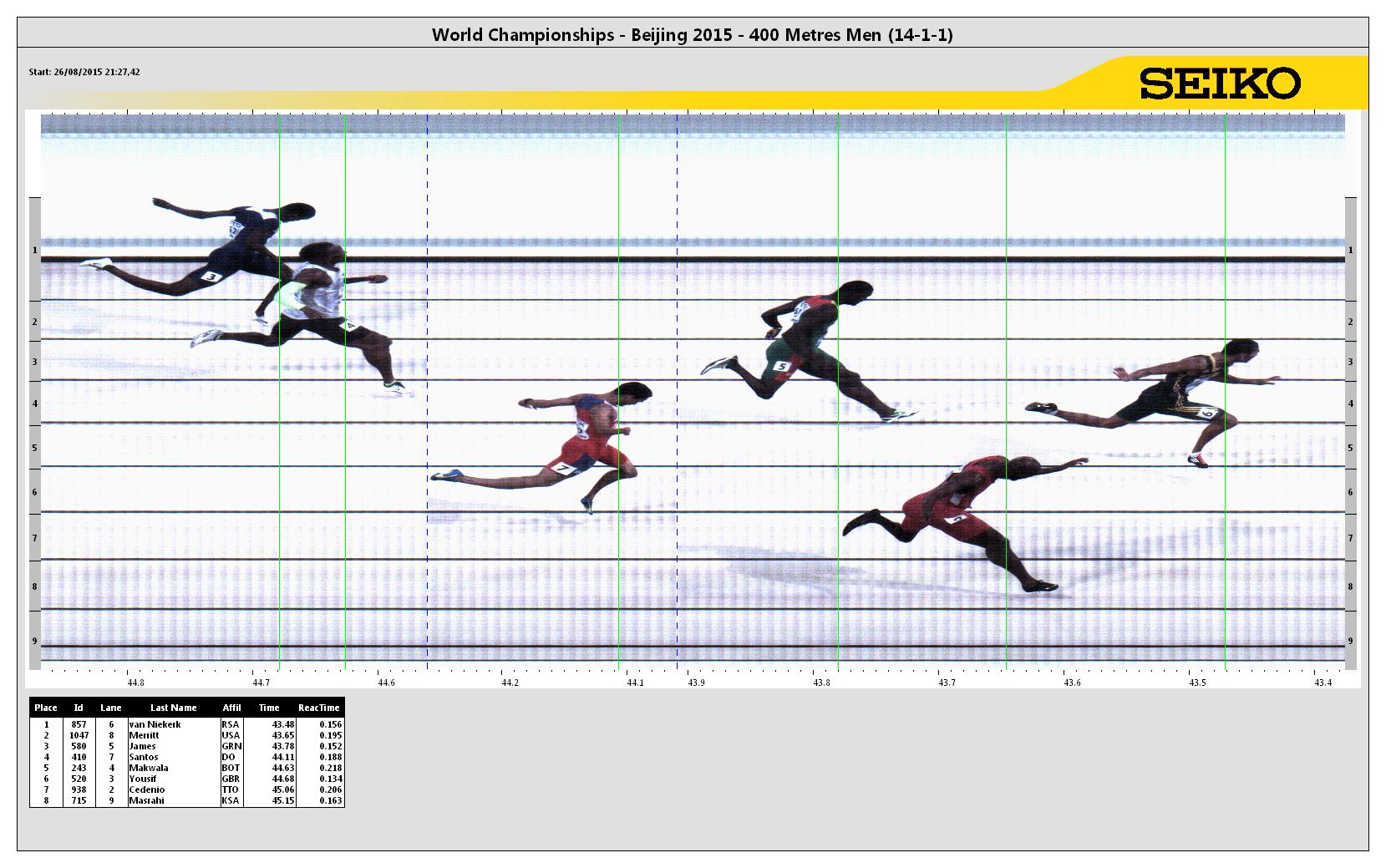

The men's 400 proved super-crazy fast.

The American LaShawn Merritt, the Moscow 2013 and Beijing 2008 Olympic champion, in Lane 8, went out hard early on the way to personal-best 43.65. He got second.

South Africa's Wayde Van Niekerk ran 43.48, unequivocally the fastest time of 2015. Kirani James of Grenada got third, in a season-best 43.78, Luguelin Santos of the Dominican Republic fourth in a national-record 44.11.

Van Niekerk's best before Wednesday had been more than a half-second slower, 43.96. His 43.48 makes him the fourth-fastest man ever at the distance: Michael Johnson (43.18), Butch Reynolds, Jeremy Wariner.

The second-, third- and fourth-place finishes? The fastest times for those positions ever at a worlds.

Van Niekerk was taken off the track in a stretcher. His condition was not immediately available.

Merritt's silver tied him with Carl Lewis as the most successful American man in worlds history, with 10 medals. He has five 4x400 relay medals (all gold, dating to 2005) and five in the open 400 (two gold, three silver).

Watch out going forward, meantime, for Isaac Makwala of Botswana, fifth in 44.63.

Makwala had shown up big-time in the semifinals, with the field’s top time, 44.11, and from the outside lane. With an electric-green sleeve on his right arm, he dropped after the finish line and gave the crowd five push-ups, a signal that the semis amounted to nothing more than a training run.

For literally decades, the 400 has been an American stronghold, dominated by the likes of Johnson, Reynolds, Wariner and Merritt. Indeed, aside from 2011 and 2001, an American athlete had won the 400 at every worlds dating to 1991.

Merritt took second in 2011 when James announced his arrival on the world stage; Merritt was coming back that year from a doping ban, and he and James have since traded off titles, James winning in London in 2012, Merritt in Moscow in 2013.

Any discussion of what this all means, if anything, must start with the acknowledgement that the rest of the world has gotten way better at events that Americans used to regularly be able to count on for production in the medals count.

To take another beyond the men’s 400, consider the men’s 400 hurdles:

Helsinki 2005, for instance: two medals, gold and silver. Osaka 2007: one, gold. Berlin 2009, one, gold.

Daegu 2011: zero, with Britain, Puerto Rico and South Africa 1-2-3, the best Americans sixth and seventh.

Moscow 2013: one, a silver, Jehue Gordon of Trinidad & Tobago winning, Emir Bekric of Serbia taking third.

Beijing 2015: Kenya-Russia-Bahamas went 1-2-3.

The Americans finished fourth (Kerron Clement, the 2007 and 2009 world champion who had spent 2014 battling injuries) and eighth (Michael Tinsley, the 2012 Olympic and 2013 worlds silver medalist, in 50.02, after crashing through the eighth hurdle).

Two Americans had put down the year’s best time before this meet, Bershawn Jackson, 48.09, and Johnny Dutch, 48.13. Neither made it to the final.

For emphasis: Kenya had won 45 gold medals at the worlds, dating to 1983, but none before Tuesday night had come in an event shorter than 800 meters.

Tuesday night’s winner: Kenya's Nicholas Bett, in a national record and 2015 world-leading time, 47.79. From Lane 9, again far on the outside.

“I am happy to win this first 400-meter hurdles medal ever for Kenya,” Bett said afterward. “I am thankful.”

Russia’s Denis Kudryavtsev, in 48.05, took one-hundredth off a national record that had stood for 17 years.

Jeffrey Gibson of the Bahamas ran a national record 48.17. That broke his own record, 48.37, which he had run in the semifinals.

“I am looking forward to more races and more training for the Olympic season,” he said afterward.

It must be acknowledged, as the New York Times pointed out in a story after Tuesday's finals, that U.S. coaches are playing a significant role in the success of other nations, and in events, such as the long jump, where memories of American success — Carl Lewis, Mike Powell, Dwight Phillips — run long.

In Tuesday night’s long jump final, the gold (Britain’s Greg Rutherford) and silver (Australian Fabrice Lapierre) medals went to athletes who train near Phoenix with the American Dan Pfaff; the bronze, China’s first long jump medal at a worlds, went to Wang Jianan, who trains with the American Randy Huntington.

The top American? Jeff Henderson, the 2015 Pan Am Games champion, ninth, one spot out of the finals.

Barber, the Canadian pole vault winner? He goes to college at the University of Akron.

As in any meet, injuries always play a role. The American 200-meter specialist Wallace Spearmon, for instance, scratched out of Tuesday’s heats upon reporting a small tear in his left calf muscle.

Beyond all that, it’s track and field, and stuff happens. Alysia Montaño, one of the best American racers in the women’s 800, in contention for a top-three finish in Wednesday’s heats, fell on the second lap after a tangle. She ended up getting disqualified.

In Tuesday night’s women’s 1500, Jenny Simpson, the Daegu 2011 gold and Moscow 2013 silver medalist, lost a shoe. She finished 11th. Ethiopia’s Genzebe Dibaba, one of the sport’s brightest new stars, won in 4:08.09.

Hopes were high in the men’s steeplechase Monday night that, for the first time ever at a world championship, the Americans — specifically, Evan Jager — might win a medal. Jager led at the bell lap but finished sixth. The Kenyans went 1-2-3-4.

How, meanwhile, to explain the men’s triple jump?

Two Americans, Marquis Dendy and Will Claye, could not summon enough Wednesday morning to make the final.

Coming in, Dendy had the year’s fourth-best jump, Claye the fifth; Claye, moreover, is an incredibly versatile athlete who at the 2012 London Games became the first man since 1936 to win medals in both the long jump (silver) and the triple jump (bronze).

Wendy, afterward: “I can’t be too, too mad, but I am disappointed.”

Claye: “I’m still in shock. I don’t even know what happened. It just wasn’t my day. That’s the only way I can see it. I went out there and gave it my all. It just wasn’t my day. I have to make my rules and get ready for next season.”