It verges on the comical to read Maria Sharapova’s indignant assertion, after she was tagged by an anti-doping panel Wednesday for two years for meldonium, that the decision is, in her words, “unfairly harsh,” and that she intends to appeal to sport’s top tribunal, the Swiss-based Court of Arbitration for Sport.

Have at it. Indeed, it’s way more likely that the relevant authorities are going to want to appeal because, in a passage that surprisingly has drawn little attention in the avalanche of stories about Wednesday’s decision, the ruling threatens to blow a barn door-sized hole in the rules as they not only were meant to be but have to be in order to have any chance at working.

To begin:

Sharapova and her entourage got ripped by the three-member International Tennis Federation-appointed panel, and deservedly so.

Rarely in the anti-doping literature do you read a case that proclaims, as this one does of Sharapova, “She is the author of her own misfortune.”

At the same time, the ruling trips all over itself in seeking to assert that she did not “intend” to cheat.

There is no quarrel with the basics: an athlete is responsible for whatever is in his or her system.

The ruling declares: “She must have known that taking a medication before a match, particularly one not currently prescribed by a doctor, was of considerable significance. This was a deliberate decision, not a mistake."

Isn't that the classic definition of "intent"?

Well, the panel goes on to say, on the one hand Sharapova “did not appreciate” that meldonium, the substance she tested positive for, had since Jan. 1, 2016, been on the World Anti-Doping Agency banned list. She tested positive on Jan. 26, after an Australian Open quarterfinal match with Serena Williams.

On the other, the panel says, Sharapova “does bear sole responsibility … and very significant fault, in failing to take any steps to check whether the continued use of this medicine was permissible,” adding, “If she had not concealed her use of [meldonium] from the anti-doping authorities, members of her own support team and the doctors whom she consulted, but had sought advice, then the [situation] would have been avoided.”

So which is it? Apples? Or oranges?

The stakes are considerable for all involved.

A two-year ban: sure, Sharapova would miss this summer’s Rio Olympics and the Grand Slams this year and next. But, like Nixon, she can come back tanned, rested and ready. She’s only 29. Williams is 34 and has come back repeatedly from time away owing to injury.

The way-more-serious risk, because it would be naive to believe that politics is not at work:

Sharapova is one of Russia’s leading athletic lights. Aside from her five Grand Slam titles, she won a silver medal at the London 2012 Olympics. More, she carried the Russian flag into the opening ceremony.

Being the flag-bearer at the Olympics is always fraught with political symbolism. In Russia, where Vladimir Putin has proven to be keenly and personally interested in the Russian team’s performance, all the more so.

A detail not addressed in Wednesday’s decision is why Sharapova, with her family — she came to Florida when she was a little girl and apparently now has a family doctor in California — felt the need in the first instance to go to a doctor in Moscow. Like, no one in American medicine was good enough? Or was there something else at work?

Beyond that:

There’s a fundamental financial risk to Sharapova’s endorsement career. For years, she was the highest-paid female athlete in the world. Forbes said she made $29.7 million in the 12 months ending June 2015. That’s more than the WADA’s 2016 annual budget, about $26 million.

The endorsement angle is almost surely why Sharapova tried Wednesday to get in front of the story — a statement went up on her Facebook page literally within minutes of the ruling itself being made public — and why she is making it seem like she is the aggrieved party at the hands of a bunch of suits interpreting the anti-doping rules.

The challenge for Sharapova is akin to the situation facing the-then Los Angeles Laker star Kobe Bryant after events in Colorado in 2003: how long, like Bryant and “Colorado,” before she gets reported about without the word “meldonium”?

The key issue at hand for WADA, the International Olympic Committee, the ITF and every other Olympic sports federation is to divine the common-sense meanings of the words “mistake” and “intent.”

Some background, according to Wednesday’s ruling:

Sharapova started started using meldonium late in her teens, prescribed the stuff by Dr. Anatoly Skalny of the Center for Biotic Medicine in Moscow.

Skalny put her on meldonium, which also goes by the brand name “mildronate,” among 17 other substances.

That’s not a typo: in all, 18.

Meldonium is a blood-flow drug. Its primary use is in addressing cardiovascular disease.

The scientific literature is filled with studies showing that it is good for — in the Eastern European vernacular — “sportsmen,” meaning big-time athletes. As a study from a 2012 “Baltic Sport Science Conference” notes, it “increases endurance properties and aerobic capabilities of athletes.”

Just a quick science note, as the ITF-appointed panel explained, reviewing the evidence of WADA’s senior science director, Olivier Rabin:

Meldonium works at the cell level. It inhibits the synthesis of a substance called “carnitine.” When that happens, the cells switch to generating energy from glucose, meaning blood sugar, instead of fat. That requires less oxygen to produce the same amount of energy.

By March 2010, according to the ITF ruling, Sharapova was up to 30 substances, including meldonium.

She began to consider 30 “overwhelming.” So at the end of 2012 she dropped Skalny. But she kept taking meldonium and two more substances, magnerot and riboxin, from the list of 30.

Did she tell the nutritionist she then hired that she was taking meldonium plus two? No.

From the start of 2013, with the exception of one 2015 visit with a Russian Olympic team doctor, did she tell any “medical practitioner” that she was taking meldonium? No.

Did she take meldonium on match days, typically 500 milligrams, in tournaments? For sure.

How many times did she take meldonium at the 2016 Australian Open? Five. Before each match.

How many times, for instance, at Wimbledon in 2015? Six.

Is there even one document after 2010 in her player records that “relates to her use of meldonium”? No.

Did she disclose its use to the anti-doping authorities on any of the forms she signed from 2014 to 2016? No.

Her coach, trainer, physio, nutritionist, WTA doctors that she consulted — did any of them know she was using? No.

Who knew?

Two people: her father and her manager since 1999, Max Eisenbud, a vice president at IMG.

This is where the story goes from the sublime to the absurd.

In a business generating the likes of $29 million in a calendar year, you would think that Sharapova would have assigned to someone two responsibilities: knowing what was on the WADA list and making sure she was in complete compliance.

As the panel put it, this is the “underlying factual puzzle.”

Eisenbud’s explanation for not reviewing the 2016 WADA prohibited list, and it should be observed that the panel notes "the evident implausibility of his account," calling the evidence he put forward "wholly incredible."

In 2015, he “separated from his wife, did not take his annual vacation in the Caribbean,” where he was in the habit of checking the list, ”and due to the issues in his personal life failed to review the 2016 prohibited list.”

In his testimony, Eisbenbud further said he had “no training” that would lead him to understand what was, and not, on the list. He also “professed not to have the basic understanding,” which every athlete subject to the WADA code is charged with, “of how the list works.”

As the panel notes, he did not explain why, among other matters, “it was necessary to take a file to the Caribbean to read by the pool when one email could have provided the answer.”

The panel, again: “The idea that a professional manager, entrusted by IMG with the management of one of its leading global stars, would so casually and ineptly have checked whether his player was complying with the anti-doping program, a matter critical to the player’s professional career and her commercial success, is unbelievable. The tribunal rejects Mr. Eisenbud’s evidence.”

As for Sharapova’s use of meldonium, it says:

“The manner of its use, on match days and when undertaking intensive training, is only consistent with an intention to boost her energy levels.”

And:

“The facts are consistent with a deliberate decision to keep secret from the anti-doping authorities the fact that she was using mildronate in competition.”

The conclusion: “… she took mildronate for the purpose of enhancing her performance.”

In the pre-2015 WADA code days, Sharapova would have gotten two years. Bam. Thank you.

Now, the penalty is four years unless an athlete can show she did not intend to cheat. That can cut you a break.

In the same manner that President Clinton’s conduct prompted an assessment of what the word “is” is, the issue before the ITF panel broke down to what “intent” means amid a conclusion she took the stuff to enhance her performance.

“If the player was genuinely mistaken as to the rules,” the ruling asserts at paragraph 70 of 104, “then she did not intend to cheat.”

Consider that for just a moment.

All anyone now would have to do is say, oops, I made a mistake?

If allowed to stand, this would make for a gaping hole in the rules.

Not a chance.

Here is the deal with an appeal, and while Sharapova can appeal, so can the ITF, WADA or the IOC.

In legal terms, such an appeal would be what’s called de novo. That’s a fancy term that means Take Two. In essence, everything starts from scratch.

That two-year ban? It absolutely could be reduced to something less.

At the same time, and especially given the assessment the ITF-appointed panel made in reviewing the conduct of Sharapova and her team — blunt, candid, harsh, pick your word — she is at considerable risk of seeing a suspension max out.

As ever, meantime, there are always two cases ongoing in any legal dispute — the one in court, and the one in the court of public opinion.

There’s a solid argument that it is spin that got Sharapova in the dilemma she’s in now. Which makes her reaction on Wednesday all the more curious.

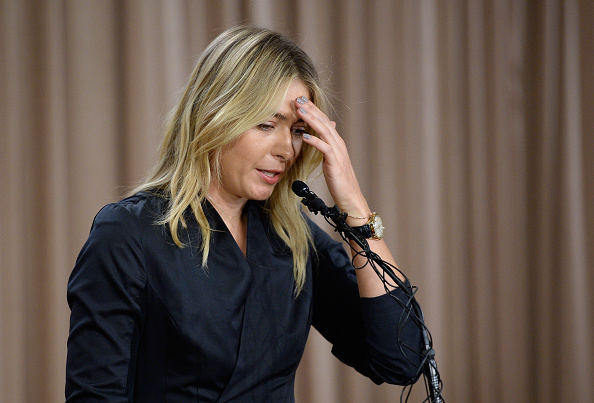

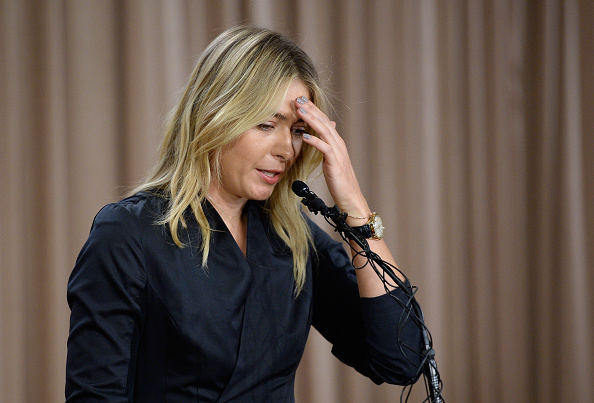

It was on March 7 that Sharapova, at a hastily called Los Angeles news conference, announced she had failed the Australian Open drug test. She sought to take responsibility. She said then that she had been taking meldonium for years for a variety of medical reasons.

Obviously, she was seeking not just to get ahead of the story but bidding to control the narrative.

What she almost surely did not count on was the meldonium deluge.

This year, more than 170 athletes, most Russians or Eastern Europeans, have been tagged for meldonium.

A number of meldonium-positive athletes have come out and said, more or less, I haven’t had any meldonium since taking some on, oh, New Year’s Eve.

Whether that is ridiculous or not:

If Sharapova had not admitted she was still using, she might well have put herself in that big New Year’s Eve meldonium boat.

Wait now to see the allegations from most or all of those athletes that the science of how long the stuff stays in your system is squishy.

For Sharapova, in this instance, getting out front got her, at least for now, a two-year time-out.

Continuing that strategy, however, this was her gambit Wednesday:

She put up on her Facebook page a note saying, among other things, “I intend to stand for what I believe is right and that’s why I will fight to be back on the tennis court as soon as possible,” signing it, “Love, Maria.”

An accompanying “short summary” purportedly prepared by “my lawyer” — she has two, so it’s not clear which — went after the doping results management process, saying Sharapova had “no input in the selection of the Tribunal which hears and decides her case, no say in how the hearing is conducted and no right to challenge the fairness of evidence admitted against her at the hearing.”

Say what?

Sharapova’s case included testimony from herself; Eisenbud; Skalny; coach Sven Groeneveld; and, as well, from two experts, Dr. Ford Vox, who reviewed Skalny’s “diagnosis and treatment,” and Richard Ings, a former chairman of the Australian anti-doping authority.

The hearing absolutely provided for cross-examination, including of Sharapova herself.

Documents, too: at the hearing, it was confirmed that Sharapova disclosed each and every document in her possession related to the use of meldonium from 2013 until Jan. 26, 2016.

She was afforded, in every regard, the process due her.

One final note:

Sharapova even argued that “any period of ineligibility” would “disproportionately affect” her, causing “a very substantial loss of earnings and sponsorships, exclusion from the 2016 Olympics and irreparable damage to her reputation.”

As if. That’s the risk you run when you don’t pay attention to the rules. No matter what you may, or may not, “intend.”