Nothing about times. No 9.5-craziness, no records this or that.

"Coach just gave me a handshake and said, 'Lay one down,' " Gatlin would say later.

Gatlin laid down a wind-aided 9.88 for the win. This was a no-doubter. Gatlin crossed the line with his left arm raised, index finger pointed to the sky: No. 1. At least on a Saturday in May in Eugene. More, here in Eugene next month at the U.S. Trials and presumably in August in Rio, to come.

The men's 100 capped a day of sun-splashed performances at the Prefontaine Classic, the one and only major U.S. outdoor stop on the international track and field circuit, with athletes aiming to round into shape for the 2016 Summer Games and, for the Americans, the Trials, back here at historic Hayward Field.

The 2016 Pre, before 13,223, termed by house announcers a sell-out crowd -- not so much, as pockets and patches of bare seats throughout the stands would attest -- marked the second act of a four-part track and field drama this year in Oregon. Part one: the 2016 world indoors in March in Portland. Part three: the 2016 NCAA championships, in about 10 days. Part four: the U.S. Olympic Trials, in late June and early July.

A number of stars proved no-shows at the 2016 Pre, citing injury or otherwise. Among them: U.S. sprint champion Allyson Felix, American long-distance runner and Olympic silver-medalist Galen Rupp and Ethiopian distance standout Genzebe Dibaba.

Those who did turn up put on, especially for May in an Olympic year, a first-rate show:

In the women's 100 hurdles, American Keni Harrison ripped off an American-record 12.24, the second-fastest time ever. Only Yordanka Donkova of Bulgaria, in 12.21 in 1988, has ever run faster. Brianna Rollins, who had held the American record, 12.26 in 2013, finished second Saturday in 12.53.

Emma Coburn also set an American record, in the women's 3k steeplechase, 9:10.76; Bahrain's Ruth Jebet won the race in 8:59.97, just four-hundredths ahead of Hyvin Kiyeng of Kenya. American Boris Berian won the men's 800 in a convincing 1:44.2; just a couple years ago was slinging hamburgers at McDonald's; in March, he won the world indoor 800; a few days ago, the Berian saga took on yet another dimension over a contract dispute with Nike.

In the women's 100, American English Gardner ran 10.81 for the win, with two-time Olympic champion Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce of Jamaica eighth and last, in 11.18; in the women's 200, American Tori Bowie ran 21.99, best in the world in 2016, with Holland's Dafne Schippers second in a really-not-that-close 22.11.

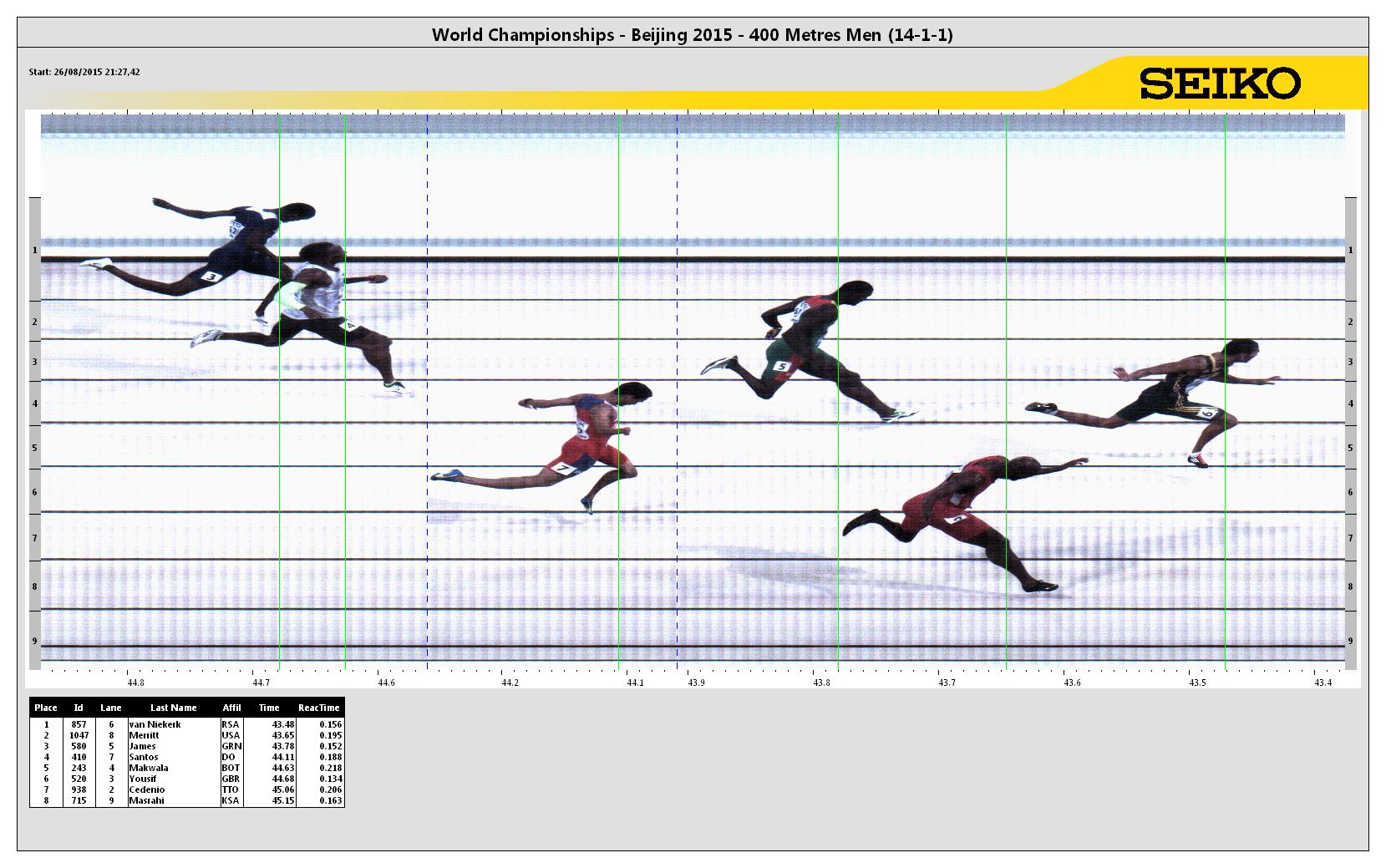

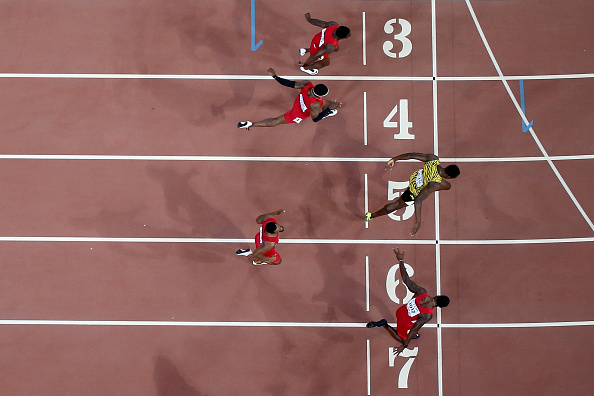

Kirani James of Grenada and LaShawn Merritt of the United States added another chapter to their extraordinary rivalry in the men's 400, James winning in 44.22, Merritt just behind in 44.39.

Jamaica's Omar McLeod continued his 2016 dominance in the men's 110 hurdles, winning in 13.06; Americans went 1-2-3 in the men's 400 hurdles (Michael Tinsley with the victory) and the triple jump (Will Claye going 17.56 meters, or 57 feet, 7 1/2 inches on his sixth and final jump, celebrating with a leap over the hurdle set up for the women's steeplechase, only to see Christian Taylor, next, go 17.76 meters, or 58-3 1/4, the two of them meeting after for a quick embrace).

In the men's javelin, Africans went 1-2: Ihab Adbelrahman of Egypt went 87.37, or 286-08; Kenya's Julius Yego took second in 84.68, 277-10.

Without Dibaba in the women's 1500, Faith Chepngeti Kipyegon of Kenya ran a Hayward Field record, 3:56.41. The prior mark: 3:57.05, from Hellen Obiri of Kenya. On Friday evening, Obiri, running this year in the Pre at the 5k, won in 14:32.02.

Also Friday evening, Brittney Reese won the women's long jump, in 6.92 meters, 22 feet 8 1/2 inches; Joe Kovacs the men's shot put, in 22.13 meters, 72-7 1/4; Alysia Montaño-Johnson the women's 800, in 2:00.78; and Mo Farah, the British distance star, the men's 10,000 meters, in 26:53.71. The top five guys in that 10k all crossed in under 27 minutes.

And then there was Gatlin, who figures heading into the Trials and Rio to have the spotlight trained on him, big time -- both for who he is and how, for most people who know about Gatlin's realistic quest to take down Usain Bolt, the way it all turned out in 2015.

At the 2015 Diamond League meet in Doha, Qatar, two weeks before last year’s Pre, Gatlin went 9.74. Only four guys have — ever — gone faster: Bolt, 9.58 in Berlin in 2009; the American Tyson Gay, 9.69, Shanghai, 2009; 2011 100 world champion Yohan Blake of Jamaica, also 9.69, at the Athletissima meet in Lausanne, Switzerland, 2012; Asafa Powell, also Jamaican and the first racer in history to run sub-10 more than 100 times, 9.72, Athletissima, 2008.

No less than five times in 2015 did Gatlin run faster than 9.79.

Back for the 2015 worlds at the Bird’s Nest in Beijing, where Bolt had raced to Olympic gold in 2008, Gatlin settled into the blocks in Lane 7 with a win streak that stretched past two dozen.

The year, and even the rounds, pointed to Gatlin. He had cruised through, winning his semifinal in 9.77. Bolt had stumbled in his semi, collecting himself late to win in 9.96.

Then, though, came the electricity of the final itself.

Gatlin got off to a slow-ish start. Even so, midway through the race, Gatlin held the lead.

Then, though, came another stumble.

This time, it was Gatlin, trying to hold off Bolt, in Lane 5.

Maybe 20 meters from the line, Gatlin lost his form.

Bolt won, in 9.79.

Gatlin took second, in 9.80, one-hundredth of a second back.

Asked Friday at a pre-Pre news conference on how many occasions he has watched the 2015 worlds final, Gatlin said, “Countless times. I can’t lie about it,” adding, “I have to make sure I study what I did wrong and also what I did right, and also my opponents as well.

“It was,” he said, “a learning curve for me.”

Sure. But, specifically, how?

“One thing I learned,” he said, “is you can’t be too greedy in trying to get speed. There’s a certain point in the race where it’s humanly impossible for a person to get any faster. So, for me, it’s just to maintain that speed, stay in control of my technique and just go straight through the finish line.”

And this:

The American sprinter Mike Rodgers typically gets out to a fabulous start. Powell performs the race's technical transitions as well as anyone, ever. The Canadian Andre DeGrasse and Gay are going to, in Gatlin’s words, “come like a bat out of hell toward the end of the race.”

“So,” he said, “these are things that you predict — weeks before the race even starts.”

Gatlin didn’t run the 100 at the 2015 Pre. Instead, he focused on the 200, which he won in a — to use his word —blazing 19.68. Gay won the 100 in a comeback statement, 9.98.

For Gatlin, by design, aiming toward the 2016 U.S. Trials and Rio, this Olympic year has gotten off to a considerably slower start.

“The 100 meters,” Gatlin said, “it’s a crazy race. It’s about balance. You don’t want to take too much away from your start and have a powerful finish, because now you’re behind. So you have to have a good solid start. You have to have a good strong finish.”

He also said, “Going into this season, you see me having good starts. The times haven’t been as blazing as last year. But you can see the strength of me coming on at the end.

“I think maybe in Beijing,” meaning this year’s race, at the May 18 IAAF World Challenge event, “Mike Rodgers had a step or two on me coming out of the blocks. I just stayed calm and just commanded the race the second half.”

Gatlin won that 100 in 9.94, Rodgers crossing in 9.97.

“It’s like blinking,” Gatlin said of the various parts of a well-executed 100.

Meaning this:

The ordinary person typically doesn’t think about blinking but, rather, just does it: “Blink, blink, blink,” he said. In the same way, the time to process what the component parts of that well-run 100, and how and why, is in training. When it’s race day, it’s go time.

Just go. That’s how you run the 100 in the blink of an eye.

Gatlin went on, crafting a new analogy, referring to the champion boxer: “I’m taking it almost like a Floyd Mayweather kind of — taking it round by round,” adding that he was “learning my technique, learning my craft, sharpening my skills and have my strongest round be the last round, the finals. Last year,” another boxing reference, ”I came out like a Mike Tyson — just swinging, knocking everything down.

“This year, I really — on a time level — don’t have a point to prove. I’ve shown the world I can run consistent, fast time. I’m strong, and I’m dominant. So this time I just want to make sure I get to the big dance, and I’m ready.”

The world lead coming into Saturday’s race at venerable Hayward Field in the 100: 9.91, by Qatar’s Femi Ogunode, at a meet April 22 in Gainesville, Florida.

Gatlin, in Lane 3 on Saturday, broke well, keeping an eye of sorts on Ameer Webb, in Lane 6, who has a solid Hayward history and had been running well, obviously in shape, early this year.

By halfway, the race was essentially over, assuming Gatlin could keep it together.

No problem.

The wind, which had been under the legal limit of 2.0 meters per second, blew just above during the race: 2.6. That made Gatlin's 9.88 wind-aided. After flashing that No. 1 sign, Gatlin jogged with the finish line tape wrapped around his neck, like a Bar Mitzvah streamer -- all to big applause.

Powell took second, in 9.94; Gay, third, in 9.98.

Rodgers got fourth, in 9.99; Ogunode, fifth, in 10.02; Webb, sixth, 10.03. China's Bingtian Su took seventh, 10.04. DeGrasse, who tied for third at least year's worlds, came up eighth, 10.05.

"I think all my races this year have been really calm and really relaxed," Gatlin said afterward, clutching a pair of Kenyan flag-colored flip-flops that a fan had thrown him.

Relaying the essence of many discussions with Mitchell, his coach, Gatlin has sought to make the course for 2016 elegantly simple:

“We just want to win. That is the motto for this year: just win. You know, it’s not about predicting what time is going to win, or [is going to get] the gold medal. It’s about getting on that line, competing, executing your race. Once you come across the line, you look across at the board and can be shocked like everyone else at the good time.”

That is yet more evidence of maturity and experience talking.

A lot of water has run under a lot of bridges since Gatlin was just 22 and won gold at the Athens 2004 Olympics in the 100, in 9.85.

In February, he turned 34.

The “20-something Justin was just happy to be there,” he said.