When Justin Gatlin first got the news — this was nine years ago — that he had tested positive for the banned substance testosterone, he literally fell out of the truck he was driving.

“While we were on the phone,” his mother, Jeanette, would later testify, “all I could hear was him screaming and screaming on the other end, and how, no, no, no, no, I’m dead, I’m dead. And we were afraid that he was going to do something to himself. He was in North Carolina, and we were in Florida. You know, to — you can’t get there. You can’t keep him safe from doing whatever. He was just — he was — he was — he was screaming. He was screaming and yelling, and he was driving, and he was in his truck, and he fell out. He stopped, and he fell out, and he fell apart. He just kept on saying, ‘I’m dead, I’m dead, I’m dead. It’s over, it’s over, it’s — I’m dead, Mommy, I’m dead.’ ”

Justin Gatlin is assuredly not dead, and his track and field career is now the farthest thing from over. For the past two-plus years, Gatlin has been the best sprinter on Planet Earth, the fastest guy anywhere anytime. Many experts expect him not only to challenge but to defeat Usain Bolt in the 100 meters at the world championships, which begin this weekend at the Bird’s Nest in Beijing. And maybe the 200, too.

"That's what everyone is waiting to see," Maurice Greene, the Sydney 2000 100 gold medalist, said Friday.

Here in Beijing as a television commentator, Greene added, referring to Bolt, "How prepared is he? Because you know Justin is prepared."

That 2006 test was Gatlin’s second go-around with the doping authorities; he would end up being banned for four years. The first test came in 2001. Because the facts and circumstances of both tests have been not just under-reported but thoroughly misunderstood, Gatlin has become to many with an interest in track and field something like Public Enemy No. 1 — particularly when compared, as he often is, to the larger-than-life Bolt.

The British press in particular has been given to depicting the races here in Beijing as a clash of "good versus evil."

In March, the Telegraph, one of Britain’s leading dailies, called Bolt a “superhero.” A few days ago, the same newspaper included Gatlin on a list of what it called “the most hated sportsmen in the world,” a “sport-by-sport breakdown of the most loathsome individuals.”

At a news conference Thursday, Bolt was asked if he was the "savior" of track and field. He said, speaking generally, not referring to Gatlin, “People are saying I need to win for the sport. But there’s a lot of other athletes out there running clean, and who have run clean throughout their whole careers. I can’t do it by myself. It’s a responsibility of all the athletes to take it upon themselves to save the sport and go forwards without drug cheats."

The curious thing is that Justin Gatlin is the farthest thing from loathsome. As Greene said, referring to both Bolt and Gatlin, "Take out everything that has to do with sports. They’re both good guys." David Oliver, the U.S. 110-meter hurdles standout, said about Gatlin, "I'm rooting for him and I hope he does well."

Gatlin comes from a strong family. His father, Willie, served with distinction for more than 20 years in the U.S. military, a Vietnam veteran, and the son wears the red, white and blue national uniform with pride. Justin Gatlin is great with kids and with track and field fans. When he got tagged in 2006, his first instinct was to cooperate with the federal government in its BALCO investigation, which he did extensively. Since coming back to the sport five years ago, he has not tested positive, and be assured that he is a marked man.

The question now is, if you allow for the very real possibility that Justin Gatlin is indeed running clean, can he run this week in Beijing for redemption?

All things are possible in sports, and particularly track and field, which for years has been bedeviled by doping. But what if -- what if -- Gatlin is, despite all the well-earned skepticism about the sport, running clean?

In his sworn testimony, Gatlin himself said, “I believe in my talent to the fullest. And I think God is trying to be, my way of showing everyone that I can do this, I can run great times without even trying to use performance-enhancing drugs.”

In an interview, he said, “I think that for so long I have shut down because of being beat upon by the media, [believing] if I say less it will go away. I’m wrong.

“At this point in time, I am trying to open up more, speak more and take it in. I am a cool guy, a nice guy. I am not trying to short-change anybody taking anything away from anyone. I welcome competition. If I get beat, I say, ‘That was a good beating.’ If I win, ‘I say that’s a good win.’ ''

The many critics of track’s doping rules say, often citing Gatlin, that two strikes should mean a lifetime doping ban. But the rules say, unequivocally, that Gatlin is allowed to run.

It's not difficult to understand why the concept of a lifetime ban might seem so appealing to so many. But theory is not real life. And it is the case that when applied to life as it is — how Justin Gatlin came to test twice — a lifetime ban would be cruelly unfair.

Those plain facts are publicly available, and sketched out in great detail, including sworn testimony in extensive transcripts from a 2007 arbitration sparked by Gatlin’s 2006 test. These documents inhabit a federal court file in Pensacola, Florida. They make it clear that:

— Gatlin’s first flunked test, in 2001, was for medication he had been taking for attention deficit disorder, a condition he had wrestled with since he was a young boy. Gatlin, at the time still a teen-ager, tried to follow the rules. Nonetheless, he came up positive.

— The second test, at the Kansas Relays in 2006, has long sparked controversy because of the assertion in Gatlin’s camp that a masseuse rubbed steroid-laced cream on Gatlin, sparking the doping positive. A reading of the record strongly suggests that story came from Gatlin’s former coach, Trevor Graham, whose credibility — amid his extensive involvement in the BALCO scandal — has to be viewed with extreme suspicion. A more likely, if unproven, explanation is that the positive test resulted from a shot or a pill described at length in the testimony.

“At the end of the day,” Gatlin said in an interview at his training base in Clermont, Florida, near Orlando, “the irony of the situation is I really do want the sport to be in a better place outside of everything that has gone on in my life.

“I look at the young guys and say, ‘I don’t want you to go through what I went through because you run fast, or run faster.’

“I want people to say he is making a difference in his sport — moving the sport along.”

—

Justin Gatlin has run fast for a very long time. In high school in Florida, he was a state champion sprinter. That earned him a scholarship to the University of Tennessee. There he was a multiple NCAA champion.

At the 2001 junior nationals, when he was 19, Gatlin tested positive for trace amounts of amphetamine.

The substance at issue was Adderall, a prescription medication. At age 9, in fourth grade, he was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder. His class had been assigned a test; Justin turned in a paper that contained a picture of a bird he had drawn instead -- the bird, on a window ledge, had captured his entire focus. A teacher suggested to his parents that Justin ought “to be evaluated.”

At UT, Gatlin was taking two summer school classes he needed to stay eligible: English 101 and Music History 350. In both classes, he had midterms the week of June 11, 2001, just before the junior nationals.

Gatlin took his Adderall to help him stay focused while studying for his midterms. He stopped taking it three days before running — why three days, exactly, instead of four or five or two or whatever, remains unclear. In the sample Gatlin gave on June 16, 2001, authorities detected trace amounts of amphetamine. A sample he gave the next day, June 17, contained even smaller amounts, consistent with Gatlin having stopped taking the Adderall on or before June 13.

The authorities and Gatlin would enter in a stipulated — meaning, mutually agreed — series of facts surrounding that test. These included:

“The course of action followed by most athletes with ADD is simply to discontinue their medication in advance of a competition. USADA,” the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, “advised athletes after consultation with their physicians to discontinue using the ADD medication prior to competition in order for the medication to clear their system.”

And:

“Mr. Gatlin neither cheated nor intended to cheat. He did not intend to enhance his performance nor, given his medical condition, did his medication in fact enhance his performance.”

The rule in doping matters is that an athlete is strictly liable for what is in his or her system.

The standard ban in those years for a first doping offense was two years.

An arbitration panel that reviewed the matter would observe:

“While Mr. Gatlin may have violated the IAAF anti-doping rules in that he did not first seek an exemption from the IAAF for his medication before he competed, he certainly is not a doper. This Panel would characterize Mr. Gatlin’s inadvertent violation of the IAAF’s rules based on uncontested facts as, at most, a ‘technical’ or ‘paperwork’ violation.”

Gatlin got two years. He then petitioned the IAAF for a reduction, citing “exceptional circumstances.” Granted. He served a provisional suspension of almost one year.

Gatlin left UT in 2002 and turned pro. He started training in Raleigh, North Carolina, with Graham’s Sprint Capitol group.

At the 2003 world indoor championships in Birmingham, England, Gatlin won the 60-meter dash.

At the 2004 Athens Olympics, Gatlin won the 100, in 9.85 seconds. He took third in the 200, in 20.03. He also earned a silver as part of the U.S. 4x100 relay team.

At the 2005 world championships in Helsinki, Gatlin won both the 100 and 200.

—

When Gatlin first connected with Graham, Gatlin’s parents were acutely concerned that Graham not only train Gatlin but, more broadly, look after their son.

“And all that was said at that time was, are you sure nothing is going to happen to Justin?” his mother would testify, recalling their first conversations with Graham.

“Are you going to make sure that he doesn’t get involved in all this other stuff,” meaning doping, “that, you know, my husband was reading about on the Internet, and I was reading about on the Internet.

“And he,” meaning Graham, “said, ‘Absolutely. That has nothing to do with us, my camp, and the way I train my athletes.”

On April Fools’ Day 2004, a prank circulated on the web that Gatlin had tested positive.

“And actually, I was at the dentist’s office,” Jeanette Gatlin testified. “Justin was home. He had not really just located — I mean, he was home for visiting — and, anyway, my husband ran across this article on the Internet saying that Justin Gatlin had tested positive. And he called me at the dentist’s office, I went running home and he — should I say it all?”

“Go ahead,” the lawyer questioning her said.

“He was packing his gun.”

“And where was he headed?”

“He was headed to kill Trevor Graham.”

“And why was [that]?’

“Because it said Justin had tested positive, and Trevor had promised that there would be nothing like that going on in his camp. He was going to take care of Justin. And he knew, he knew that [Justin] already had that other offense hanging over him.”

“I trust you stopped him?”

“We stopped him, because … I’m saying — I’m saying, how can you go kill this man? I mean, you are going to — anyway, my husband is crying. Tears are coming out of his eyes. He’s crying. He’s ready to kill Trevor. And then Justin goes on the Internet, and he sits there, and he looks at it, and he says, Dad, Dad, Dad, Dad, read the bottom of it. Read the bottom of it. And the bottom of it said, April Fool’s.”

“Do you know who posted that?”

“I have no idea but we were very angry about it. And my husband was saying that — you know, they can’t be playing jokes like this with people’s lives. and then all of a sudden, somebody else may read it and believe it without going through it, like he didn’t go through it. And we never did find out who posted it …”

—

Track and field has a distinct rhythm to the outdoor season. Athletes build toward summer, which three years out of four brings either a world championships or Summer Games.

The Kansas Relays is an early-season fixture on the circuit, a three-day meet held every almost year (since 1923) in April.

On April 22, 2006, Gatlin ran in the 4x100 relay at those Kansas Relays with his Sprint Capitol teammates. They won, in 38.16.

On July 29, Gatlin announced to the press that he had tested positive for testosterone at the Kansas Relays.

Two mysteries relating to the 2006 test have long endured.

The first is what authorities thought they would find — that is, why bother to test — at such an early-season affair.

The second is why it took so long — three months, April to July — for the test from those Kansas Relays to become what’s called, in the vernacular, an “adverse analytical finding,” or a doping positive.

The court files explain.

From May 2004 through October 2006, Paul Scott supervised the reporting of athlete urine samples at the WADA-accredited UCLA laboratory. In that capacity, he supervised the reporting of Gatlin’s Kansas Relays sample. He would provide an April 7, 2008, sworn affidavit relating what happened:

Though the sample was provided April 22, 2006, it wasn’t until June 15 that the lab itself reported an adverse analytical finding. This nearly two-month delay was, as Scott would say, “not common practice.”

The reason for the delay?

Gatlin’s sample initially produced a negative result — meaning he apparently was clear — under what’s called the T/E ratio test, the standard test used both in- and out-of-competition to screen for testosterone. Indeed, Scott said, Gatlin’s sample was originally reported to USADA as a negative.

About one month later, USADA got in touch and requested that the lab perform what’s called a “longitudinal analysis” because, Scott said, because “they had reason to believe that the athlete was using testosterone,” adding, “I now know this athlete to be Justin.”

USADA executive Travis Tygart did not, Scott said, inform the lab of the “nature of the ‘tip’ nor the basis for his belief.”

The lab did as asked, and concluded that Gatlin is what’s called a “low-mode individual,” who — to make it simple — lacks a particular enzyme, with the effect that the T/E ratio is typically very low and does not much change if that individual is administered “exogenous testosterone,” from a source outside his body.

The lab told USADA Gatlin was low-mode. “I am not aware of whether we recommended or USADA requested that a Carbon Isotope Ratio test be performed,” Scott said, referring to a test that is both far more sensitive and way more expensive, in the range of several hundred dollars.

In June 2006, the lab performed the CIR test. Bingo. A positive test.

Why did USADA ask for the further analysis that led to the positive?

In another set of stipulated facts, the answer:

At that same 2003 world indoors at which Gatlin won the men’s 60, Michelle Collins won the women’s 200. Her 22.18 would have been an American record but it was never ratified. Instead, after being linked to the BALCO matter, she admitted using illicit substances. Ultimately, she would get a lengthy suspension.

In May 2004, Collins told USADA that Trevor Graham, her former coach, “told her to appear at track events with no drug testing and to use fast-acting drugs to avoid detection.”

She last trained with Graham in 2001, before Gatlin met up with Graham, the legal document stresses.

USADA “considered this information provided by Michelle Collins and decided to test at the 2006 Kansas Relays, an event at which it had not previously tested,” the document says.

In late 2005, USADA notified USA Track & Field and Kansas Relays organizers it would be testing that next April at the meet.

Gatlin was picked for testing after his relay team won first place; he had run the anchor leg. “This selection” for testing “was in accordance with USADA’s routine selection criteria for track and field relay events,” the document says.

—

When he was on the road, Gatlin had a reputation as the room service king.

He testified, “I have this paranoia about people messing with my food, or especially, from the first incident where I don’t like to let people do anything orally to my food, and my water, and I don’t like people touching my stuff or around me.”

On June 15, 2006, the room service king, ever careful, learned in a three-way call — with his agent, Renaldo Nehemiah, and his parents — that he had tested positive at the Kansas Relays.

Gatlin testified:

“It was a nightmare that I live again, from my first situation, and I found, I prided myself, I would never put myself in that situation again, and it happened to me again, and I remember the only thing that I kept saying over and over was that my life was over. I didn’t know what to do. I mean, because, running is, running is what I love. I love to run. And I never would do anything like that, because I know I have the support of my family and my friends.”

Jeanette Gatlin, in testimony, asked if Justin had ever said “that he knowingly took a substance”:

“Oh, absolutely not. Absolutely not. He kept on saying, ‘I don’t know how this happened. I don’t know how this happened. I’m careful. I watch everything. I know one thing: I’m dead.’ That’s all my child kept saying, was that he was dead. He was dead.”

Asked what he did in the weeks between when he found out he had tested positive, and July 29, when word went out to the media, Gatlin responded, “Other than cry?”

Jeanette Gatlin was asked if the experience had taken a toll on her son:

“Most definitely. Most definitely.

“When Justin came home,” to Florida from the Sprint Capitol base in Raleigh, “before we went back and relocated him, Justin would be sleeping, you could hear him at night. You could hear him, he just uh-huh, ugh-huh, ugh-huh, you go in there and he is just jumping. He is just jumping. He is cold and sweaty, and he’s crying, and he’s breaking down, when you talk to him, in the daytime, baby, think about it, think about what happened, he just breaks down, he starts crying and he’s shaking and falling apart. He’s not sleeping at night. He’s restless, I’m going through getting up all time of night, going in there and [checking] on him.”

She also testified, “Not only has my child, Justin Gatlin, suffered and [is] still suffering, his name, his reputation. We have all suffered. We have all suffered. I have — I’m bald, not by choice. This is the haircut that anybody that knows me has never seen on me before. I have long hair. My hair was coming out in clumps. I had to go and have my hair cut off through the stress of this. I have never suffered high blood pressure before until this.

“Justin — Justin walks tall, and he’s strong, and he’s strong and he’s positive. But he — I see the hurt in him. I see how he’s just, well, can — Momma, can I buy a pair of jeans? Can I buy a pair of jeans? Do we have money? Can I buy a pair of jeans?”

Nehemiah testified that the second test cost Gatlin “5, 6 million dollars.” Gatlin, Nehemiah said, had grossed $1.549 million in 2005; projections in 2006 alone, the agent said, were for “anywhere from $2.5 to $3 million” in 2006 alone. Owing to the positive test, Nehemiah said, Gatlin’s 2006 gross: $280,235.

After winning 2004 Olympic gold, Nehemiah said, there had been a meeting with Gatlin, his parents and officials from both Nike and USATF, a “coming-to-Jesus talk.” He said the tenor of the conversation went like this: “OK. You are no longer Justin Gatlin. You are the United States of America. And everywhere you go, you go this great site, and everybody likes you so, you know, there’s a lot that’s being put on your shoulders.”

“Did he embrace that burden?” Nehemiah was asked.

“He embraced it, yes, wholeheartedly.”

Jeanette Gatlin continued: “You know, he’s suffering,” referring to her son. “He doesn’t know where he’s going to get another paycheck, what’s going to happen and how he’s going to continue to live.

“This,” she said, “is his life.”

Shortly after news of the positive test broke, the Escambia County, Florida, Sheriff’s Department asked if Justin could come speak to their graduating cadets. You’re aware, Jeanette Gatlin said, of the case? Yes, came the answer, she said, relating that this nonetheless was the response: “We want Justin to come. We believe in him. We have faith in him.”

He ended up speaking to that cadet class; too, to 4,000 students, high school and college, about the D.A.R.E. anti-drug program, with his mother saying “it was the biggest turnout they ever had”; to church groups — “not our church,” Jeanette Gatlin stressed — where “he spoke to them, and he read from the Bible, and he told them to obey the parents, obey the laws, stay away from drugs, keep their body clean. Keep their minds straight, keep them focused.”

Justin Gatlin spoke as well with Jeff Novitzky, the-then federal agent running the BALCO inquiry. On August 16, 2006, Gatlin met with Novitzky for five and a half hours in New York, voluntarily traveling to the meeting from Florida. At the end of that interview, Novitzky asked Gatlin to make undercover phone calls to Graham, as a means both to judge Gatlin’s credibility and to potentially gather evidence against Graham.

Gatlin agreed.

In all, Gatlin would make roughly a dozen calls to Graham and Randall Evans, an assistant coach. Throughout, the authorities viewed Gatlin as a cooperating witness.

Novitzky would testify as well.

This exchange, with Tygart:

“Well, did you ask him if he used any prohibited substances?

“Yes.”

“And what was his response to that?"

“His answer was no, never knowingly."

Novitzky also offered this assessment, referring to Gatlin, “Again to the best of my ability, and as I have testified before, throughout this case, I have not obtained any evidence, despite these hiccups and despite these concerns, looking back now historically, I have not obtained any evidence of his knowing receipt and use of banned substances.”

—

Thus the core question: what happened that prompted the 2006 positive test?

The dog-ate-the-homework theory that got advanced is that masseuse Chris Whetstine rubbed a cream containing steroids on Gatlin.

Where did this story come from?

Gatlin, in testimony, referring to Graham: “He said that he went and looked at the Internet to find out what the cream was that he thought Chris Whetstine used, and he came across DHEA,” banned as a testosterone precursor.

A moment later, in further testimony: “He said that while Chris was applying the cream on me in Kansas that he saw a — I think he said a pink tube, a white tube and a pink squiggle on it,” purportedly made by Sarati Laboratories, “and he went back and referenced that, and he came up with DHEA.”

Asked if Graham’s “speculation” was “accurate or not,” Gatlin testified:

“It’s a very strong speculation, and I wouldn’t say it was a bull’s eye, a bull’s-eye, but I think that — it’s more of an oval-shaped peg than a square peg fitting in a circle.”

Why, he was asked, put so much weight on what Graham would assert?

“Well, to do research on it, especially doing research with my lawyer at that point in time … we researched DHEA, and some of the stuff that we learned about it, and kind of went along with the story of what happened.”

Gatlin was asked, did you see the tube Whetstine had? No.

Did you ask to see it? No.

So, “you didn’t hear about the tube with the squiggly S on it until after you had been reported positive, correct?” Yes.

“… And the only person that you heard that from was Trevor Graham, correct?” Yes.

Graham did not testify in this hearing. Nor, for that matter, did Evans.

But Whetstine did.

Referring to Graham, Whetstine said, “Well, golly, I thought I was … I mean, in 2006, I would have to say it was probably the best year in our relationship that we ever had. We would go on long walks together, talked about politics, religion, he showed an immense amount of concern for Justin Gatlin in trying to keep him on focused [sic] and on track, so that we could attain our goal."

Answering questions from Tygart:

“Do you have any knowledge of how Justin Gatlin tested positive?"

“None, sir."

“Did you apply any prohibited substances to Mr. Gatlin?"

“No, sir."

“Did you apply testosterone cream to Mr. Gatlin?"

“No, sir."

More:

“When you heard of Justin Gatlin’s positive tests, what came to your mind as the possibility of how this occurred?"

“I had no idea. I had no idea how it could have occurred."

“Did you do any introspection as to whether anything you did might have caused this?"

“Well, I knew that nothing that I did would have inadvertently caused it."

Later, in an exchange with one of the arbitrators supervising the case:

“Have you heard of Sarati Laboratories?"

“No, sir."

“Have you heard of a cream, Deep Hydrating Essential Aloe Cream?"

“Only after this investigation."

“Did you ever have any tubes that were white tubes with pink squiggles or stylized letter S's on them?"

“No. I can provide you a little insight into — I’m going to step out on a limb here, and call it Mr. Graham’s alibi. And let you know — I want to be careful, because I don’t want to be inflammatory.

“I’m a pretty big supporter of Justin Gatlin, and I don’t want to believe that Justin did anything wrong, OK?

“But in the light of the truth and fairness, where they’re concocting this story from is that my sponsor Biotone, OK? There’s a — I am given a product to distribute from Biotone, BioFreeze, to athletes and therapists; not only therapists that are under my direction, but other therapists, who would be, you know, ostensibly of some notoriety, if they were to be making a plane trip from one place to another.

“And one of the bottles that Biotone has — I think it’s called the Dual Purpose Massage Cream, a product that I don’t use. I use an oil, which I may have already described in my testimony. And this Biotone Dual Purpose Massage Cream has a pink band on it.

“And so, somehow, they have leapt from the Prefontaine Classic," an annual track meet in Eugene, Oregon, "which is probably, I think, June 7th — some time in early June when that product first showed up for distribution to my staff, courtesy of Biotone, and something that they claim that happened months prior.

“It’s a product I don’t even use. It’s solely for distribution to my staff."

“… But you don’t know that the Dual Purpose Massage Cream that you have described contains any prohibited substance?"

“If that were the case, every athlete at the Prefontaine Classic that year would have tested positive."

“Why is that so? Because you said you don’t use it."

“Because I distribute it to 17 other therapists. I give out a goodie bag that has all Biotone and Biofreeze products, PowerBar and literature from StrongLite …"

—

Whetstine also testified that in May 2004, he went with Evans to a pharmacy in Monterrey, Mexico, where he — Whetstine — bought Voltaren cream, an Advil-like anti-inflammatory that is not uncommon in American track and field circles, even though it’s not typically available in the United States.

“And I would like to note at that time,” Whetstine testified, “I watched the witness Randall Evans buy pure testosterone.”

At a different point in the hearing, Whetstine was asked by another of the arbitrators to elaborate.

“You made a reference to Randall Evans purchasing testosterone in Mexico?"

“Yes."

“Do you know what he was using that testosterone for?"

“Well, he told me it was for sexual performance. I don’t care what he was using it for. I was furious. He — I was livid."

“This was in 1998?"

“No, this was in 2004, yeah, because he was in Mexico in 2003 and we went back in 2004. And as he was purchasing two packages that had 8 vials apiece. I mean, he was saying it was for topical application for sexual enhancement. And these were bottles — you know, like they have the — like a skinny neck, like a tight neck with a — like an aluminum cap? And that to me means that — that’s like what you see in the hospital. I mean, that’s something that you can inject in somebody.

“And I was furious. And as he was paying for it, I left. I wanted nothing to do with that and told him so. Made sure that I was not in the airport with him, that we left on — you know, did not arrive at the same time for our departures, called my girlfriend — actually, on Justin Gatlin’s phone, called my girlfriend, expressed that I was furious.

“And she inquired about it, and you know, I get — it does have some levity to it. She said, well, if that’s what he’s saying, honey, you don’t need any of that stuff. I mean, she was joking with me."

“So why were you furious?"

“I was extremely furious at why — you know, I was furious."

“Why were you furious?"

“He’s buying testosterone, sir. That’s a prohibited substance. I don’t want any exposure or knowledge of anything."

“So I mean, were you — did you consider that he was buying it for other athletes?"

“I didn’t care what he was doing. I didn’t want him doing it in front of me."

“When you say it’s a prohibited substance, I’m a little bit — it was legal for him to buy that in Mexico, correct?"

“I don’t know. You know, the story is you can get whatever you want in Mexico, and his wife is Spanish. He actually says his wife works for the FBI, was his claim, and she was an FBI agent and was bilingual, and so, I guess he had some lingo, but — what was the question?"

“Well, I guess I’m just trying to figure out — I’m trying to figure out why were you furious? It seems to me if he was buying it for himself, it would be OK. If he was in Mexico, obviously, he shouldn’t be transporting it across the border.”

“But if he was buying it for other people, it seems to me — especially for athletes — that would be a valid reason for being furious."

“Sir? My integrity, hard work and my word are all that I have to go on in this business. I do not want to be exposed to, have knowledge of any illegal activity, OK? And I don’t care what he’s buying it for. I don’t care what he’s buying it for. OK?"

—

Gatlin had long had problems with tweaky hamstrings. That was the case in the spring of 2006. HIs right hamstring was not responding.

Red blood cells take oxygen to the muscles. When the body can’t make enough red blood cells, one response is to take vitamin B12.

Taking the vitamin B12 orally was not doing the job, Gatlin testified. So he asked a doctor what to do; the doctor recommended a B12 injection directly into the hamstring itself.

It is also the case — well-known in the appropriate circles — that administering testosterone directly would help in recovery.

Who, Gatlin was asked on the record, did he talk with about the prospect of getting a B12 shot?

Graham, Evans and, as well, another sprinter who at one time was in the Sprint Capitol camp.

On April 6 or 7, Gatlin testified, he got a shot of what he believed to be B12.

At his house. From Evans. With Graham in attendance.

Whose idea was it, Gatlin was asked, to get a B12 shot? To ask the doctor about such a shot?

Graham, Gatlin testified.

“Did you — was it normal for you to get any sort of a shot by Randall Evans?”

“No, it wasn’t.”

“Had you ever gotten a shot from Randall Evans?”

“No.”

“Were you concerned about getting a shot from Randall Evans?”

No, because the doctor had “explained to me,” Gatlin said, “that Randall Evans was taking classes to become more medically inclined under his wing …”

“Before Mr. Evans injected you in your hamstring,” Gatlin was also asked, “did you ask him whether he had ever injected performance-enhancing substances into any athletes?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Because I didn’t believe he did. It was a B12 — sitting right here, it’s a B12 shot. That’s why I was concerned about my leg. I was concerned if he was juicing up some of the athletes that I didn’t know.”

At another point in the testimony:

“… You are a gold medalist, double world champion, and you allow this person, who is learning to give injections, to inject you in your hamstring while you are injured?”

“He wasn’t a person who was learning. He was my assistant coach.”

At the same time, Gatlin also sought to depict himself as not completely trusting of Evans. Before submitting to the injection, Gatlin said, he looked at the package: “It was a white box, and it said B12, and it said ‘Vitamins’ right across the front of it. It was an unopened package. It was sealed, and so was — the needle was also sealed,” just “a regular needle.”

A B12 injection comes as a clear red liquid solution. The red is vivid.

Crucially, Gatlin was never asked whether that B12 shot was red — neither by his own lawyer or on cross-examination.

Moreover, B12 injections are typically administered via the buttocks or shoulder, areas less susceptible to pain.

The day after the B12 shot, Gatlin did testify, he took a Voltaren pill — supplied, he said, by Evans.

The pill and shot came about a week before the Mt. SAC meet in California. There, Gatlin ran a relay leg; his team took second.

A week later: the Kansas Relays.

After Mt. SAC, Gatlin testified, he felt like he was back to 100 percent.

Again, Evans did not testify. Nor did the doctor.

Novitzky, meanwhile, was on the stand for this from USADA’s Tygart: “OK. Agent Novitzky, have you — are you aware that Randall Evans has denied giving an injection of B12?”

Objections came from both Gatlin’s lawyer and from government attorneys, and the question never did get answered.

Novitzky did testify that during that five hour-plus interview, Gatlin “categorized the pill .. as a ‘Voltaren bean.’ When myself and my partner heard the word ‘bean’ used — based on our investigation to that period of time, we had heard testosterone and Decadron,” a corticosteroid, “being referred to as a ‘bean,’ so it kind of spurred our interest when we heard that.”

During that interview, Gatlin was asked to describe the pill.

Novitzky testified, “He described it as green with a V on it.”

He added, “This wasn’t an instance where we just left it. We followed up and said, ‘Are you sure that’s what it looked like?’

“He said, ‘Yeah, he was sure it was green with a V on it.’

“We came to find out later, much later, months, maybe a year later, that he told someone else that the pill was brown, and brown is the color of these testosterone and Decadron pills, so we had some concern about that.

“We actually had Mr. Gatlin, his mother and [Gatlin’s lawyer] on a phone call, and brought that to their attention. They did come up with an explanation about his confusion regarding the coloring, and that he had been taking an Excedrin, which was a green, but these Voltaren pills that he had been taking all along were brown. You know a little bit unclear, where that leaves him, you know, in the credibility issue in that department.”

Another matter of credibility, Novitzky said, related to Angel “Memo” Heredia, long believed in track circles to be a chemist of considerable repute — who, as Nehemiah related it in testimony, “was not a Trevor Graham fan.”

Nehemiah, saying he was seeking answers to how Gatlin could have tested positive, commissioned Heredia to write a report.

Ultimately, Nehemiah said, the report “wasn’t comprehensive at all,” describing it as a “waste of our time.”

The report, after much negotiating, cost $10,000. But because of an accounting glitch, Heredia got paid $10,600.

“The Memo memo,” as it came to be called, ultimately made its way to Novitzky. From the agent’s point of view, the concern was simple: the government had no idea initially that Gatlin’s entourage had retained Heredia.

“This was all unbeknownst to us,” Novitzky said. “He didn’t — we found out about this second-hand, not from them. And that was a big issue toward us, in terms of, you know, cooperation and credibility, because typically, when we’re dealing with cooperators and looking at these issues, you know, one of the issues with a cooperator is full disclosure of everything.

“And while we did get some explanation that they weren’t sure that we needed to know this, and they thought we already knew some of this, the bottom line, it was not the case that they told us this was going on when it was going on. So that was another issue that came into play.”

—

It might be reasonable to assume that Gatlin would — in his own case — get some benefit from cooperating with Novitzky and the feds. In fact, he got none.

The majority of the three-member arbitration panel that heard the case noted it “finds much merit in Mr. Gatlin’s position and the facts of his cooperation, which were substantiated by the pertinent government witness, supports the extensive, voluntary and unique nature of Mr. Gatlin’s assistance.”

Even so, the rule at instance was super-precise: “substantial assistance” had to result directly in an anti-doping agency “discovering or establishing” doping by another person.

Yes, Gatlin cooperated, USADA acknowledged; yes, he took considerable risk; but, no, the dozen or so phone calls didn’t lead directly to any such violation.

As far as the Whetstine theory, the panel majority said, “the fact is that there is no substantiation of Mr. Gatlin’s naked claim.” It added, “There was no evidence that any of the creams used by the physical therapist actually tested positive.”

It said, “More importantly, the evidence submitted by Mr. Gatlin did not eliminate the possibility of intentional use or the possibility that he was the unwitting victim of doping by members of his coaching staff.”

Further, “Simply stated, this Panel does not know with any degree of confidence how the testosterone entered Mr. Gatlin’s system; transdermally or by pill or injection.”

That being the case, it said, “USADA makes a strong argument. If Mr. Gatlin cannot prove how the testosterone entered his system, and he did not, he cannot prove two significant facts. First, that it was the physical therapist that placed the testosterone in his system transdermally; and second, that he did not intentionally take testosterone.”

“Finally,” it said, “while Mr. Gatlin seems like a complete gentleman, and was genuinely and deeply upset during his testimony, the Panel cannot eliminate the possibility that Mr. Gatlin intentionally took testosterone, or accepted it from a coach, even though he testified to the contrary.”

It gave him four years off.

A 2008 review by another three-member panel, this one from the Swiss-based Court of Appeal for Sport, left it at that: four years.

—

Those four years, Gatlin said in an interview, were miserable. He moved to Atlanta and, to make money, taught sprinting to 8-year-olds.

“One thing I learned on my journey and it’s really true, kids are the least judgmental. Kids looked at me and never brought up any incident, never questioned anything, and they said, ‘Mr. Gatlin, I am just trying to get fast like you. Teach me.' ”

There was that. But he said, “I lost every endorsement. I lost everything.”

He also said, “I was so depressed, Me, my mother and my father, we are a core. We became stronger when i went through my ordeal. Going through the ordeal broke us down. My mother lost hair. For a woman, that’s a big thing. She prayed every day to the point where she was like, what is prayer doing? Nothing is being answered! She doubted her faith.

“I would honestly say my dad was more depressed than anybody. His son carries his name and gave him the most pride, and to go through what I went through made him so depressed. He didn’t talk a lot.”

As for Justin Gatlin himself, during those four years, he said, “I think that’s where track Justin met real Justin.

“It’s not a cliché to speak in the third-person sometime. I have to tell you how I experienced it. I didn’t see any worth my life. I wasn’t running. I wasn’t being acknowledged. I was looked upon as the bad guy. I was ready to enlist in the Army. I was ready to become a police officer. This is real: if I die, if I took a bullet, at least I took it for something I believe in — America.

“I have never been a person to have suicidal thoughts. But I said, ‘What is the worth of my life? Who am I?’ That’s when I had to say: ‘There is more to Justin than just running.’ “

It was with that attitude that Gatlin came back to the sport in 2010.

He worked himself back to a bronze at the 2012 London Games in the 100, behind Bolt.

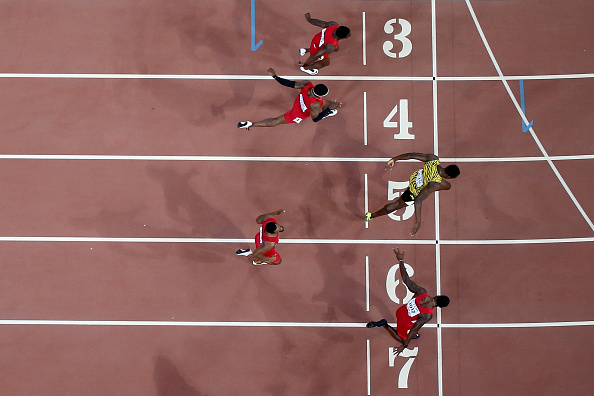

The turning point came the next year, at the 2013 worlds in Moscow. The 100 went down in a pouring rainstorm. Bolt won, again, in 9.77, crossing the finish at the precise moment lightning flashed across the sky — an incredible, indeed indelible, picture.

That frame also shows Gatlin. He is behind Bolt, and to the Jamaican’s left. Gatlin would finish second, eight-hundredths back, 9.85.

Gatlin said, “I don’t want to step out of my boundaries and my respect for other opponents [but] when I look at that picture, that’s when I said to myself, ‘I think I can beat this guy. I can challenge this guy outright.’ “

To do so, however, he had to submit — to his coach, Dennis Mitchell. Gatlin said he had to accept Mitchell’s word as gospel, to let technique do the work for him in his races.

Until that lightning flash in 2013, Gatlin said, he had — whether consciously or not — been trying to do it his way. From that moment on, he said, it has been Mitchell’s way.

Mitchell typically draws a torrent of criticism from those who know he, too, tested positive during his days as a champion sprinter. There’s a back story there, though. Mitchell tested positive for what he relates as inadvertent use of DHEA. But who voluntarily testified for the government in its investigation of Graham? Among others, Mitchell.

Mitchell said, "I testified under oath in front of the feds that Trevor Graham coerced me into taking growth hormone."

He also said, “When you are dealing with the federal government the first thing you don’t do is lie. Because they will get you.”

“I was a witness for the good guys,” he added. “I wasn’t prosecuted. I wasn’t threatened. I wasn’t put on trial for lying. I was a 20-minute witness for the federal government, against Trevor Graham, to tell everything about my life and his life that would incriminate him. That’s what I did. And I took a hit for the good guys.

“And I knew that when I did that, either the sport was going to herald me as a good guy or they were going to kick me out as a villain. I rolled the dice. I said,’Dennis, everything you have been through in the sport, all the great achievements you have had in the sport, the sport will not turn its back on you.’ "

Doing what Mitchell says, Gatlin has not lost since the end of 2013. This year, he has run 9.74 in the 100, 19.57 in the 200.

The American records: 9.69 (Tyson Gay, Shanghai, 2009), 19.32 (Michael Johnson, Atlanta Olympics, 1996).

Under Mitchell's direction, Gatlin has lost roughly 30 pounds; the science of sprinting increasingly has come to recognize that leg strength -- not being top-heavy -- is what counts. He also has worked in the weight room to re-make his slimmer self and at improving his start.

"I wear medium shirts now," Gatlin said of his weight loss. "A large would be hanging off."

"Any person who has watched this kid, who knows track and field, can see the technique changes," Mitchell said, adding a moment later, "2014 is the year he woke up smart. He put his mind to it and went for it."

“When I step on the track, my percentage of worrying about opponents in the race has dropped significantly,” Gatlin said. “All I worry about is executing my technique, executing my race strategy and competing against time.”

He also said, “I feel there’s a difference between being in the zone and being dialed in. I have learned that the last two years. The zone is good; a lot of athletes are in the zone. But when you are in the zone there still can come a lot of variables; you can still worry about certain opponents, about what can go wrong. When you are dialed in, you worry about one thing,” execution of race strategy, “and that one thing will handle everything else.”

As an example, he said, “If you look back at all the races I have had just this year, if you look back with a careful eye, you will see difference. From the 19.68 I ran,” a 200 last July 18 at a Diamond League meet in Monaco, “to the 19.57,” this June 28 at the U.S. nationals, "the end of my race and my last 100 meters was way more relaxed, way more turnover.

‘I wasn’t fighting my technique. I just let my technique turn over. In my 19.68 race, I was more worried about running the curve.”

In his home bathroom, Gatlin said, he has hung what he calls a “vision board,” posts of what he wants to achieve. On the board, he said, are the times 19.30 and 9.68.

“At one point in time, my vision board was names. I have changed that. Now it’s numbers. Now it opens up a different door.”

Anything is possible in track and field, which for years and years has been marred by doping, and at the highest levels. As difficult as it may be for some skeptics, indeed cynics, the matter is straightforward: to believe that Justin Gatlin is doping is to believe he does not want to go through that door.

To assume that Gatlin is cheating is to believe he would risk his new Nike deal. Mitchell, too, has a new deal, and he and his wife have a baby. The mortgage gets tough to pay when there's no income.

Beyond all that, to believe that Gatlin is doping is to say he wants to stumble back to the wilderness — lost, angry, the sort of son who would disrespect his parents, who would make his mother’s hair fall out again, who would risk the certainty of a third strike and a lifetime away from the very thing that gives him so much joy, indeed meaning, in life.

Which seems more logical? Which more reasonable?

“I found me,” Gatlin said of his four years away.

He said, “I had to step back and realize, you know, just because everyone doesn’t agree with what I am doing doesn’t mean they are against me.

“Just because someone doesn’t step up doesn’t mean they aren’t for me.”