Attention, all you sanctimonious, moralistic, smarter-than-everyone-else know-it-alls who traffic in rumor, half-truth, character assassination and worse when it comes to USA Track & Field, and in particular the effort to win Olympic and world relay medals. Do yourselves a favor, along with everyone who values civility, dialogue and tolerance: give it a rest.

Under the guise of anonymity, the stuff that gets said, and in particular written, about USATF and — now, in the aftermath of last week’s Penn Relays, where one of two U.S. men’s 4x100 teams again had a problem exchanging the baton — is way, way, way beyond the bounds of decency, fair comment and constructive criticism.

To be blunt: a botched handoff is not armageddon.

Nearly 18 years of writing about the Olympic movement has led to a great many track meets. Across those years, U.S. relay difficulties have been duly noted. At the same time, fans and self-professed experts rarely understand or appreciate the real-world difficulties that go into executing the relays, especially a bang-bang event like the 4x100.

If the result is not gold, there’s typically just a lot of yelling and name-calling. It’s as if the United States ought to win every single time simply because that is the American way.

That is thoroughly unrealistic.

And the time has come for everyone to take a deep breath and appreciate the three core Olympic values: friendship, excellence and respect.

In this instance, especially: respect.

Five of the six U.S. relay teams at the 2016 Penn Relays were winners. Five of six.

That sort of mark underscores the goal, as articulated by Duffy Mahoney, USA Track and Field’s chief of sport performance:

“We are trying to build a better mousetrap. We are trying to take a difficult situation and do the best job we can, or a better job, at optimizing the chance of medal attainment,” in particular at the Olympics and world championships.

—

As the International Olympic Committee notes in a new promotional series, "Sport is respect. It's not all about winning."

Since he took over as USATF chief executive four years ago, Max Siegel has expressly sought to lower the volume of the conversation in and around the sport. He has preached, and practiced, dialogue and cooperation.

So, too, the current board chair, Steve Miller.

The results of Siegel’s first four years are, by any measure, remarkable:

Up, and in a big way: annual budget (to more than $35 million in 2016), federation assets, prize money for elite athletes, partnership agreements, merchandise sales, USATF.tv users and page views.

You can’t be creative at the leadership level when, as the sport used to continually find itself, you’re figuratively scrounging from paycheck to paycheck. A 23-year Nike deal, worth in the neighborhood of $500 million, means the federation finally has financial stability.

As it happens, beginning in 2016 roughly $1.8 million is due to be distributed to athletes over and above USATF tier and development funding, and other programs. What that means: $10,000 for making the Olympic team as well as bonuses of $10,000, $15,000 and $25,000 for Olympic medals. A top-tier athlete who wins a national title and competes for the national team but does not medal: base pay, $45,000. That same athlete, with an Olympic gold: USATF support of $95,000.

Internationally, the USATF board of directors made the right call in nominating Stephanie Hightower for the policy-making executive council of the sport's international governing body, the IAAF, in place of Bob Hersh. She led a USATF sweep at IAAF balloting last August that also saw the election of Britain’s Seb Coe as president.

Track and field is not — repeat, not — the NFL. Nor the NBA or MLB. Nor even the NHL.

Athletes are not unionized. They are independent contractors. You want the American way? Every athlete is, to a significant extent, his or her own brand — with the exception of certain national-team events, such as the Olympics and, recently, the Penn Relays, where it’s entirely reasonable for Nike to want to appropriately and reasonably leverage its sponsorship. That’s one of the elements it’s paying for, right?

The disconnect is fundamental: track and field is perhaps the only sport in the U.S. Olympic landscape in which there remains a dissident cohort seemingly hell-bent on destroying anything and everything in the pursuit of precisely the sort of petty, personality-oriented politics that used to wrack the U.S. Olympic Committee before a 2003 governance change.

Some of this is tied to the very same underlying issue that for years vexed the USOC: the battle for authority between paid staff and volunteers.

Some of it, especially in the relay landscape, involves rival shoe companies vying for influence, position or an uncertain something vis-a-vis Nike.

Some of it is just nasty and wrong.

Siegel, who is the only African-American chief executive of a national governing body in the U.S. Olympic picture, was targeted in recent months by racially charged emails. So were others at the Indianapolis-based federation. The matter has drawn the attention of law enforcement.

It’s intriguing to draw a contrast between, on the one hand, the almost-total lack of public condemnation from some of the sport’s most outspoken activists after those emails were published and, on the other, the loud voices that proved keenly critical of Siegel and USATF in the aftermath of a rules violation at the 2014 U.S. national indoors.

Further disconcerting: what gets written on message boards at sites such as Lets Run and a Facebook page entitled “I’m tired of USATF and IAAF crippling our sport.” At least on Facebook there are names attached to the comments. The stuff on Let’s Run is so frequently laced with such venom, almost always posted via pen names, that it’s a wonder some enterprising lawyer hasn’t already thought to ask what’s appropriate.

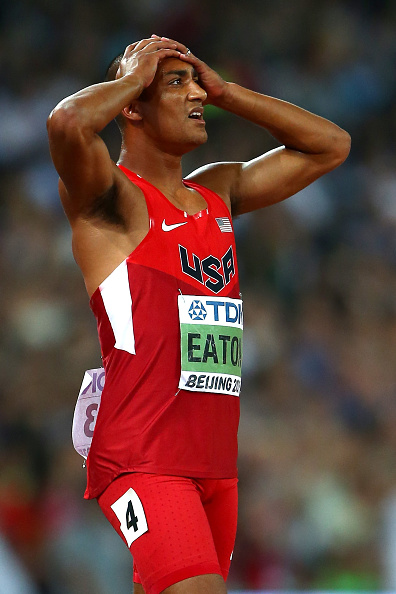

At this year’s Penn Relays, U.S. runners Tyson Gay and Isiah Young could not cleanly execute the third, and final, hand-off in the men’s 4x100. This led to a Let’s Run message-board string relating to the U.S. relays coach entitled, “Fire Dennis Mitchell Now.” The site highlighted the link on its homepage; as of Thursday, five days after the race, the link still sat on the page.

In and of itself, the message-string headline is innocuous. But the discussion underneath veers off to allegations of various sorts about Mitchell. Some of it is arguably the worst kind of hearsay. Almost none of it deserves to be aired in a public forum without corroboration and real evidence.

Late in his career as an active athlete, Mitchell served time off for doping. That fact tends to enrage his detractors. Typically, they fail to note, or to care, that the Olympic movement’s rules when it comes to doping make expressly clear that everyone deserves second chances. Especially a guy who was team captain at the 1996 Atlanta Games.

Moreover, in 2008, Mitchell testified for the federal government in its case against North Carolina-based coach Trevor Graham, one of the central figures in the BALCO scandal.

As Mitchell said in a 2015 interview, “I was a witness for the good guys. I wasn’t prosecuted. I wasn’t threatened. I wasn’t put on trial for lying. I was a 20-minute witness for the federal government to tell everything about my life and his life that would incriminate him. That’s what I did.”

Mitchell said, referring to the coach-athlete relationship, “I want my athletes to understand I am the caretaker of their dreams. I have no options. It’s all due to what I have been through. It’s because I have been with a coach who has been the opposite — who doesn’t care about your life, your family, your dreams.”

He also said, “I am on this earth to fulfill a life of servitude,” adding, “I am here to coach. I am here to be a beacon to others who are lost. I am comfortable with that. My job is not to be a CEO. I am a nuts-and-bolts guy. That is what God has given me … he didn’t give me the great ability to be other than I am. I have embraced it. It hasn’t come easily. At one time, it was taken away.”

—

At recent Olympic Games and world championships, the list is long of U.S. relay missed handoffs, disqualifications and other errors. Indeed, after the 2008 Beijing Games, USATF went so far as to commission a report that in significant part sought to identify root causes and fixes.

In the 2008 relay program, on the men's side, of the six guys who ended up in the 4x1 relay pool, only one had run his leg in any of the three relevant meets (Stockholm, London, Monaco) before Beijing: Darvis "Doc" Patton, who ran leg three, and then only in two of the those preceding meets. At the Games in the semifinals, Patton and Gay, anchoring, could not compete an exchange.

It's worth observing that Patton and Gay were not at the relay practice camp prior to the Games. This goes to the issue squarely confronting the American program now: getting together to practice and compete as much as possible.

In essence, Mitchell is, at least through the 2016 Games, a big piece of the fix.

USATF hired him in a bid to bring winning structure and order to a scene that should be simple — getting the stick around the track — but, in fact, is layered with complexities.

Despite the well-publicized glitches, there are signs the U.S. relay program can, genuinely, meet expectations.

For instance, the 2015 Penn Relays showed real evidence of development: Notre Dame grad Pat Feeney stepped in on short notice to run a 44.84 anchor to give the U.S. 4x400 team a win over the Bahamas.

At the 2015 World Relays a few days later in the Bahamas, a U.S. foursome — Mike Rodgers, Justin Gatlin, Gay and Ryan Bailey — went 37.38 to take down Usain Bolt and the Jamaicans.

There are also signs of just how difficult putting, and keeping, together such a program can be.

Bailey, struggling with his hamstrings, has essentially been MIA since last June’s U.S. nationals in Eugene, where he false-started out of the 100 and then withdrew from the 200.

It’s also the case that, in the relays, stuff happens. At those 2016 Penn Relays, Gay and Young could not connect; the year before, Rogers, Gatlin, Young and Bailey beat the Jamaicans (without Bolt), winning in 38.68.

After this year’s Penn misfire, former U.S. standout Leroy Burrell declared it “might be time for a bit of regime change with the leadership,” adding a moment later, “There’s no reason we shouldn’t be able to get the stick around. I saw thousands of relay teams yesterday — maybe not thousands but hundreds of relay teams get it around. But the professionals can’t. That ’s just not good for our sport.”

His comments came after this from Carl Lewis, the 1980s and 1990s sprint champion, at the USOC media summit in Beverly Hills, California: “America can’t cross the line so something’s going on here. Nine-year-olds never drop the stick.”

A note: Mike Marsh, Burrell, Mitchell and Lewis made up the four who ran a then-world record 37.4 to win gold in the 4x1 relay at the 1992 Barcelona Games. The current mark: 36.84, run by Bolt and the Jamaicans in the London 2012 final.

Another note: three of four on that U.S. 1992 relay were members of the famed Santa Monica Track Club: Marsh, Burrell and Lewis. That leaves -- who?

One obvious follow-on: Marsh, Burrell and Lewis, teammates, could — and did — run together regularly in practice and competition.

—

The starting place for any elite-level relay discussion has to be this: the Olympics and worlds are not high school or college.

It’s one thing to execute when a men’s 4x1 relay is 45 or 50 seconds. It’s another at the highest level, when the time drops to 38 or even 37-ish seconds.

“I’m tired of people who have been part of Team USA take shots at Team USA,” Gatlin said in response to Burrell’s remarks. “To put us in the same boat as high schoolers is insulting.”

Added Rodgers, “People keep pointing their fingers and downing us, but nobody has ever tried to come out there and help us. Nobody from the past. Not Carl or Leroy. They haven’t been out there. I can’t really respect their opinions because they’re supposed to be leaders in our sport and in the USA, and they’re not coming out there to drop some knowledge on us, so I don’t care what they have to say.”

The next variable: in a perverse way, the U.S. program suffers from a luxury of too much talent. Other countries know all along who the top five or six runners in the 4x1 or 4x4 might be, because there are only that many, and so they can run together, repeatedly. Obviously: practice makes perfect.

In 2015, the United States saw 33 men and 37 women meet the Rio 2016 Olympic qualifying standard in the 100. For men, that’s 10.16; for women, 11.32.

At those 2015 World Relays, who took third in the men’s 4x1? Japan. There are not 20 guys in all of Japanese track history who have run 10.16.

Next, and sticking with the men’s 100:

For the 2016 Olympics, there will be six guys in the U.S. men’s relay pool. But officials clearly can’t know until the evening of July 3, after the U.S. Trials men’s 100 has been run at venerable Hayward Field in Eugene, who the first four guys across the line are going to be.

The other two spots? Officials similarly have to wait until other events are run; those two spots might be filled, after discussion, by another 100-meter place finisher, 200-meter runner or even a hurdler or long or triple jumper. Whoever.

Because there’s probability but there literally cannot be certainty about who the top four guys might be, that makes it a virtual impossibility to practice, practice, practice together.

On top of which:

It’s unclear what gets accomplished — other than disruption — when athletes who are sponsored by shoe companies other than Nike get pulled from U.S. national-team relays, and particularly on short notice.

Five years ago, Ato Boldon, the 1990s Olympic sprint medalist who is now widely considered the sport’s premier television analyst, put forth a list of six “rules” he suggested the U.S. program adopt. A number still deserve solid consideration today, including:

“Rule 3 is managers/agents stay the $%&* out of practice/discussions. What YOUR client ‘wants to run’ means nothing.”

The week of the 2015 Penn Relays, adidas pulled no fewer than eight athletes out, citing uniform issues.

At the 2015 Diamond League meet in Monaco, U.S. officials weren’t told that Trell Kimmons, who also is sponsored by adidas, wasn’t going to run until he was literally in the tunnel about to compete.

After the Monaco meet, USATF, working in conjunction with its’ athletes’ advisory committee, worked out an entirely workable compromise, the details of which went out to all involved in late March or early April of this year, meaning everyone had more than ample notice:

In general, athletes would be free to wear what they wanted — both to and from meets, and in practice. The exception: one domestic and one international relay competition, typically USA v. the World at the Penn Relays and Monaco or a similar summer event. At those two events, on the day of competition, athletes would have to wear Nike to and from, and of course at the meet.

On the men’s side in the 100, six of the top 10 Americans run for Nike: Rodgers, Gatlin, Gay, Young, Bailey, Remontay McClain. Strike Bailey. So down to five. All five sent word they were in for Penn.

Wallace Spearmon, who is now unattached, also said he would be in. So, six.

Treyvon Bromell, the 2015 worlds bronze medalist in the 100, is a New Balance guy. USATF got told he would be a no-go.

Kimmons and Marvin Bracy are adidas. No-go, USATF was informed.

On the track, Rodgers, Gatlin and Gay had staked the Americans to the lead before that missed final handoff, Gay to Young.

“I can’t fault them for wanting to sell shoes,” USATF high performance director Mahoney said.

But, he said, “In this case, it’s almost penny-wise, pound-foolish. What are they trying to accomplish?”