A lengthy inquiry

In the iconic 1985 ahead-of-its-time Cold War-era cinematic classic, Rocky IV, Sylvester Stallone and Dolph Lundgren do battle in the boxing ring.

Stallone of course is the American Rocky Balboa. Early in the film, Lundgren, cast as the emotionless automaton Soviet Ivan Drago, beats the former heavyweight champ Apollo Creed, ultimately to death, in an exhibition bout. “If he dies, he dies,” Drago says.

Rocky decides to challenge Drago. He sets up camp in the Soviet Union on Christmas Day. He does roadwork in deep snow and works out using ancient equipment. Finally, the match. Predictably, Drago gets the better of it early, only for Rocky to come back. In the 15th and final round, Rocky knocks Drago out, avenging his friend Apollo’s death and, of course, affirming truth, justice and the American way, but never mind that.

During the fight, the once-hostile Soviet crowd, seeing how Rocky had held his ground, began to cheer for him. After winning, he grabs the mic and says, “During this fight, I’ve seen a lot of changing, the way you felt about me, and in the way I felt about you … I guess what I’m trying to say is that if I can change, and you can change, everybody can change!”

Rocky Balboa and Ivan Drago in 1985’s ‘Rocky IV’

This brings us directly to arguably one of the most interesting men in international sport, Umar Kremlev, the Russian who is head of the International Boxing Assn., and to the perplexing relationship between the IBA and the International Olympic Committee.

That is, whether the IOC will deal at all with the IBA and with Kremlev. Whether there can be a path toward renewed dialogue — as Rocky Balboa would put it, everybody can change. Or whether things are too far gone. Like, way too far gone.

Critics of Kremlev, and there are many, want to find fault with a great many things. Their criticisms get back to two things, really. One, he is not controllable. Two, and more importantly, he is Russian. In most of the Western world, this — right now — is not a desirable attribute.

IBA president Umar Kremlev at pre-tournament news conference in Tashkent, Uzbekistan

The question is whether the criticisms miss or gloss over real, substantive, indeed wholesale change at the IBA. The IOC suspended it four years ago.

The tension between the IBA and IOC has fueled, particularly in the West, a commonly accepted narrative. The narrative holds the IBA primarily at fault.

The narrative is furthered by a series of complexities. These include:

Layers upon layers of politics. Many players, some significant number of whom are from non-Western nations. A bias in the Western press that’s either, take your pick, decidedly for Western entities or deeply against those entities from places it doesn’t know or care to understand. Plus, there’s – Russia.

The fundamental complexity is that this is, at its root, a story about money. For boxers, life-changing money. To be candid, for most Olympic-style athletes, it would be life-changing money. Amid the complicated politics, the issue is elemental: shouldn’t the athletes themselves have the agency to chase their dreams — and that hard cash?

Sports officials consistently say they’re in it to pave the way for athletes’ dreams. The IBA is doing just that. Who else? What other federations? Money is complicated. But the thing about money is that numbers are facts. Facts do not make for a narrative. Facts reach for the truth.

If one reads the extraordinary facts detailed in the three reports prepared by the Canadian law professor Richard McLaren, especially the one from June 2022 — all of which has been in the public domain for nearly a year now but hardly reported — one gets an entirely different picture of how the tension between the IBA and IOC came to be. Moreover, McLaren, who is hardly a softie, particularly on matters related to Russia, having inquired at length into Russian doping issues, said at the federation congress in Abu Dhabi in December, “IBA is changing significantly. There’s been observable progress within the organization.”

Many if not most Western news accounts paint the situation as one where the IOC holds most if not all the cards, particularly with regard to the Olympics, especially in Los Angeles and 2028.

Is this so?

Big picture, the issues between the IBA and IOC underscore the way the Olympic Games have over nearly two generations undergone a significant programmatic change. A close look at the situation — as in everything everywhere, money talks and you-know-what walks — indicates without any doubt that the IOC has since 1988 slowly been squeezing boxing, perhaps out of the Games no matter what.

It’s also clear, looking ahead just a few years, that the IOC’s longstanding revenue model, heavily dependent on U.S. television rights, is at risk. The facts make crystal clear that other international sports federations, themselves almost entirely dependent on the IOC for financial survival, would perhaps do well to take note of the way Kremlev has overseen an IBA fiscal re-do that, independent of the IOC, has made it not only solvent but indeed thriving while hugely benefitting its athletes and the sport.

Thus the key questions:

Who really needs who? Does the IBA need the IOC and the Olympics? Or is it the other way around? And, ultimately, is there a path toward compromise?

—

In February 2022, just days after the close of the Beijing Winter Games, Russia invaded Ukraine.

The war is wrong. That is not up for debate. Here is to an end as soon as possible.

When the war began, IOC president Thomas Bach was confronted with the latest in a series of crises in his presidency linked to Russia.

Over some weeks and months, the IOC adopted a series of measures that, among other matters, recommended — emphasis, recommended — to the international sports federations that individual Russian athletes be allowed to compete only as neutrals; that athletes who “actively support the war cannot compete”; and, further, that athletes contracted to the military or national security agencies not be allowed. For purposes of simplicity, Russia also includes Belarus.

Moreover, in the language of the IOC, the recommendations “make clear” — once more, recommendations — that “no Russian and Belarusian government or state official can be invited to or accredited for any international sports event or meeting.”

Russian teams — as opposed to individuals — “cannot be considered.”

And no Russian government or state official can be invited to or accredited for any international sports event or meeting

At the time the war commenced, three summer sports IFs — to use Olympic jargon for the international federations — were led by Russians: fencing, shooting and boxing. The oligarch Alisher Usmanov has since “temporarily” stepped aside as fencing president. Italy’s Luciano Rossi took over from Vladimir Lissin at shooting after an election last November.

That leaves boxing. And Kremlev.

There is no question, none, that Kremlev — who before becoming IBA president was secretary general of the Russian boxing federation — can move at the highest levels in his country. In a letter he wrote to the IOC in November 2021, he said the national federation “appreciates the support of Russia’s leadership and I remain grateful for having enjoyed this support.” But, he said, “The abuse of political connections is another allegation that I firmly reject.”

It is also the case that political connections – and positions of import in governments worldwide –run rampant within the IOC membership.

Kirsty Coventry, who chairs the IOC’s oversight board for the Brisbane 2032 Games, is the minister for sport in Zimbabwe. Princess Reema Bandar Al-Saud, who too sits on that Brisbane 2032 committee, is the Saudi ambassador to the United States. Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović, who chairs the all-important IOC committee that reviews bids for future Summer Games, is the former president of Croatia. And so on.

Typically, to be a “friend of the state” has its advantages within the IOC. Except, apparently, when it does not. Because it is indisputable that politics — and perceptions of what is what in Russia — have not only shaped but continue to fuel the dominant narrative in the West when it comes to the IBA. This has significantly worked to the IOC’s advantage in the court of public opinion, as this tweet from Michael Payne indicates; Payne, a former IOC marketing director, retains a shrewd sense of how matters are moving in Lausanne, Switzerland, where the IOC is based.

That Payne was responding to this particular pointed observation — this is deep inside baseball when it comes to the IBA — is, in a word, rich.

At any rate, big picture, since the boycotts of 1980 and 1984, it has been gospel within the Olympic movement that boycotts only serve to hurt athletes. Bach, a gold medal-winning fencer from West Germany, could not take part in the Moscow 1980 Games because of the U.S.-led boycott. One of the key lessons of the 1980s boycotts, particularly for Bach, is that athletes needed agency. Fast forward: since 1992, all athletes have been professionals.

Bach has said many times over the past months that sanctions against the Russian state are one thing. But athlete participation is another. “What we never did, and never wanted to do, is [keep] athletes from participating in sports only because of their passport,” he has said.

Under Kremlev, the IBA has allowed Russian boxers to compete, under their colors and flags. This is sharply at variance with other IFs. A collection of Western nations opted to boycott the IBA 2023 women’s championships a few weeks ago, in New Delhi; some number also boycotted the 2023 men’s tournament, in Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

Kremlev’s view on the matter is simple. Each IF is entitled to run its sport the way it sees fit. The IOC recommendations are just that, recommendations. And, as he said in an official visit to China just before the Tashkent championships, “Sports are higher than politics. When sport begins, all debates and conflicts must end.”

He also said on that China trip, and this is the essence of the Kremlev philosophy, one that knifes through the politics: “Boxing is a social elevator for boxers from different countries who can provide money to their families by winning.”

—

As Theodore Roosevelt once said, to win you have to be in the arena.

As Umar Kremlev said in an interview in Tashkent, sounding remarkably like Thomas Jefferson if Jefferson were expounding on sports, and keep in mind this is a Russian: “Some people become sports officials and they think they have become a deity and they cover up with democracy. Democratic elections are when officials are elected and officials become service providers. When there is free choice, free speech and free elections, that’s what democracy is.”

Kremlev’s notion of service is getting all those qualified to do battle into the arena and then awarding cash to winners. Plain and simple.

Facts:

Prize money for this year’s men’s affair in Tashkent was $5.2 million. For the women’s championships in New Delhi, it was $2.4 million.

Exactly 100% of that $5.2 million (and the $2.4 million at the women’s event) went to the athletes, per the IBA. The money is paid directly to the athletes, not through their federations.

Next year’s championships will see the men’s championships offer $10.4 million in prize money; the women’s, $4.8 million. Same deal — all the money to the athletes.

The prize money is underwritten, entirely, via a licensing fee paid by the host. Thank you, Uzbekistan 2023, et cetera.

For 2024, IBA has five cities vying for the men’s worlds; it had three for the women’s and opted to return to Astana, Kazakhstan, site of the 2016 women’s worlds. It’s not rocket science to understand that IBA can, say, pick one site for the 2024 men’s tourney and then negotiate with the others for succeeding years. For a federation, this is an enviable position to be in: an entity with a desirable product.

“The development of boxing and the issue of organizing future events were discussed,” an IBA news release noted of that late April visit Kremlev made to China. “The IBA president emphasized that the development of boxing in the region is very important.”

Back to Tashkent 2023.

The championships ended May 14. A gold medalist won $200,000. Silver, $100,000. Bronze, $50,000.

Sportswriter math: 200 + 100 + 50 = 350k per podium, right? In boxing, there are two bronze medals. So, it’s 200 + 100 + 50 + 50 = 400k. Now easy-peasy multiplication: 400k times 13 weight categories = $5.2 million. The women, 12 categories.

Who handled administrative costs? Also easy-peasy: local organizers. It’s in the contract, per the IBA.

For the 2024 men’s event, gold will mean $400,000.

By 2027, IBA intends at the men’s event to award a cool $1 million for gold, $500,000 for silver, $250,000 for bronze.

Kremlev, speaking in Russian through a translator at the pre-tournament news conference in Tashkent:

“When parents are sending their kids into sports,” meaning boxing, “they should understand that in the future their kid will be able to support his family.”

This immediately after saying:

“Our goal as an international association is to support the sportsmen, to let them win, to have their flag up and, I know, but having their anthem flying is not enough. Boxers should be popular and afforded not only with meals but money. Championships will be no exception. Champions should not only represent their country but also should be able to support their families, their loved ones.”

Let’s compare:

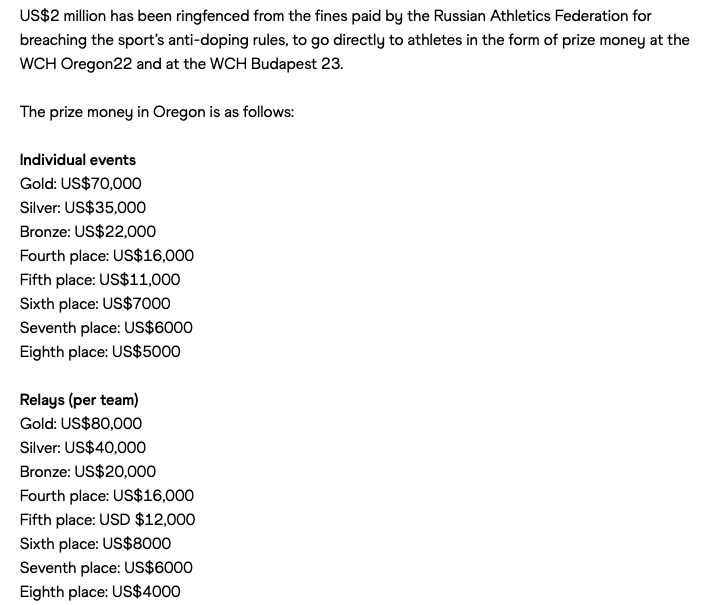

Prize money for the 2023 world track and field championships this summer in Budapest will be exactly the same for 2022 in Eugene, Oregon, World Athletics staff said, referring to a July 2022 breakdown posted on the federation’s website. The federation will be offering just under $8.5 million total; the total includes — across the two championships — $2 million in fines from the Russians for doping violations. Gold in an individual event: $70,000. Silver, $35,000. Bronze, $22,000. A world record, paid separately — $100,000.

The 2023 world swim championships in July in Fukuoka, Japan? Total prize money: $5.67 million, roughly the same as the $5.72 million from Budapest 2022. Gold in a swim race, per World Aquatics: $20,000. Silver: $15,000. Bronze: $10,000. A world record: separate $30,000.

Prize money for the 2023 World Aquatics championships in Fukuoka, Japan. Swimming is denoted by ‘SW’

Like this year in New Delhi, last year’s IBA women’s championships, in Istanbul, paid out $100,000 to gold medalists. Ireland’s Amy Sarah Broadhurst won the 63-kilo class. With the money, she bought her first house, at 25 years old. She would later say, “To own a house at my age is a great achievement, and I’m very proud of this.”

Broadhurst didn’t compete in New Delhi. Ireland boycotted. In all, 19 national federations from 17 countries, all Western, stayed away.

Who did that benefit? Amy Sarah Broadhurst?

In Tashkent, 19 countries — 21 national federations — boycotted, again all Western. In all, 538 athletes from 107 countries showed up.

The Western media operates in an echo chamber. To read only its coverage, one would believe that these stay-away Western nations — in particular the United States, and Britain — are somehow the power players. This thoroughly ignores Russia, the former Soviet states, China, India and the nations of the emerging Global East and Global South.

In Tashkent, the top five in the overall medals table were Uzbekistan, Cuba, Russia, Kazakhstan and then a four-way tie, with three medals apiece, Spain, India, Georgia, France. Azerbaijan, Brazil, Mongolia and Armenia won two medals apiece.

In New Delhi, the top five overall: China, Kazakhstan, Colombia, India and then a three-way tie, with three medals apiece, France, Australia, Russia.

If the criticism of these medals counts is that of course these nations won more because other Western countries didn’t show up – the reality is that it’s these nations that got Kremlev elected.

It’s also these nations that increasingly make for a power bloc within the Olympic space. The Olympic movement depends, above all, on solidarity among the more than 200 nations of the world. The outrage that the nations of the West have directed at Russia is not felt – not hardly – universally, and the Russians have noisily been recently floating trial balloons about organizing a parallel BRICS Games: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa make up some of the world’s leading economies and account for four of every 10 people on Planet Earth. On May 2, TASS reported, Russian sports minister Oleg Matysin briefed president Vladimir Putin about plans for such a “very relevant” event, noting that Russia chairs the BRICS consortium in 2024 and eyeing the “prospect of … expansion in terms of new member states.” Last Wednesday, Putin said he wanted a Games plan by this July 1 and gave the job to prime minister Mikhail Mishustin, a signal of its import.

How concrete is a BRICS sports event in 2024? No one knows. Most critically, how on board would China be? Again, no one knows.

But don’t be naïve: the Sochi 2014 Games cost a bundle. Putin would assuredly spend a lot – a ton – of money on a 2024 endeavor.

In 1984, the Soviets – who boycotted the LA Olympics – organized what they called a Friendship Games.

To be clear: a BRICS Games, or a reprised Friendship Games, to run after the Paris 2024 Summer Games, would be a look-in-the-mirror event that would look to challenge – directly aiming to undercut if not replace – the Olympics.

In this regard, does Kremlev perhaps thus represent the emergence of nothing less than an existential threat: a Russian-controlled federation with ample finance that essentially does he, as it, wants? Is that why the IBA and the IOC are, truly, at odds?

On his own recently concluded trip to China, Bach, the IOC president, met with, among others, premier Li Qiang, No. 2 in that government. The IOC release, referring to Li, and one must read this in the context of the upcoming 2023 Asian Games in Hangzhou as well as China’s interest in a 2036 or 2040 Summer Games and more:

“He stressed the fruitful cooperation with the IOC and underlined the importance of the development of sport and China’s readiness to make an even greater contribution to the Olympic movement and its unifying mission.”

This is the IOC, in its way, seeking – understandably – to exert leverage with China.

Then again, as the “no limits” partnership between them has made clear, China and Russia share an inordinate number of interests.

And as Alexander Stubb, the former Finnish prime minister and foreign minister, explained in a devastatingly clear May 10 analysis in the Financial Times, there is a “general misconception” that the world is united against Russia.

He said, “It is not.”

Some 40 nations, most Western, have sanctioned Russia. Only two are from Asia. None from Africa. None from Latin America.

“The new world order,” Stubb said, “will be determined by a triangle of power oscillating between the Global West, the Global East and the Global South.”

The Global South, he goes on to say – led by the likes of India, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Nigeria and Brazil – makes up some 125 states from across Asia, Africa and Latin America.

This is the power bloc that elected – that re-elected – Umar Kremlev.

Stubb’s column winds up with an observation derived from the worlds of diplomacy and politics but that’s spot on, too, when it comes to Olympic sport:

“The Global West is mistaken in framing the new order as a battle between democracies and autocracies. The situation is much more complex than that. For the Global East it is about power and managed dependencies. For the Global South it is about agency, representation and economic growth and development. If the Global West wants to maintain the remnants of a liberal world order, it will have to start conducting a more dignified foreign policy. This does not mean sacrificing values on the altar of interests. It means listening and engaging rather than preaching and moralizing.”

Isn’t there, then, significant value in perhaps listening to the Russians, and paying attention in particular to Kremlev, who is acutely engaged with – in Olympic jargon – his stakeholders?

“The Russian Olympic family is about to make a difficult choice, which is being pushed by colleagues from Lausanne,” Russian Olympic Committee president Stanislav Pozdnyakov said last Monday, TASS reported.

“Olympic solidarity is one of the main principles of Olympism. I am sure that all members of our sports community are fully committed to this principle, but those who interpret it too willfully, with a high probability they will incur moral responsibility to their comrades, country and history.”

The day before the men’s tournament closed in Tashkent, Kremlev paid a visit to Rufat Riskiev, the “Tashkent Tiger,” winner of silver at the 1976 Montreal Games, gold at the first world championships in Havana in 1974.

Kremlev gave Riskiev that world championship belt, and a trophy in the image of Andrei Borzenko, a fighter whose story – of dominating some 100 underground fights in the Nazi camps – is a legend in the Soviet states but virtually unknown in the West. And then Kremlev said Riskiev would be taken care of financially for as long as he lived, that IBA is a family.

“I’m very touched,” Riskiev said. “Before [this] everyone forgot about me.”

No question, zero, there is an obvious PR upside to such a visit. Then again, almost all sports officials talk about their communities as a “family.” When was the last time the president of an Olympic sports federation made such a commitment? Publicly?

Who doesn’t understand that boxers see this sort of thing and naturally would be more inclined to believe their president has their interests, short- and long-term, in mind?

French boxer Soufiane Oumiha // Getty Images

That same day, the IBA announced another sweetener – for the first time, prize money for each losing men’s quarterfinalist, $3,000 apiece. The math: 52 fifth-place fighters times $3,000 = $156,000. Again, another underwritten expense, per the IBA.

“I would like to express my deep gratitude to the president of the IBA Umar Kremlev for the support of those who remained one step away from the medal,” said Serik Temirzhanov of Kazakhstan, a silver medalist in the featherweight category at the 2021 championships in Belgrade, fifth in Tashkent. “I am sure it will be a great incentive for all boxers.”

Heavyweight runner-up Aziz Abbes Mouhiidine of Italy was among those on the podium to weigh in: “IBA is doing their best for us, giving also the possibility to win a huge amount of money,” adding, “All of us want to win the medal and the money.”

Mohammad Abu Jajeh of Jordan, lightweight bronze medalist: “I am very proud of myself for reaching this level of competition and making history for my country as it is our first medal in the world championships and, Allah willing, this is the first step toward glory,”

The International Monetary Fund says per capita income in Jordan in 2023 is roughly $5,000. That bronze medal is 10 times that, $50,000. Abu Jajeh added: “And about the prizes that the IBA gives and the support for boxers, I want to thank the IBA for supporting the boxers. It is something very important to keep going. Because all boxers need monetary support in their career.”

Soufiane Oumiha of France, the lightweight winner, silver medalist at the Rio 2016 Games: “It is true. The prize money motivates.”

—

Very few sports officials are super-wealthy the way Kremlev is wealthy and, because his IBA presidency has no bearing whatsoever on his standard of living, he tends to mean what he says about his devotion to boxing and boxers.

Because he has connections — within Russia and without — he was able, upon election as IBA president in December 2020, to secure a sponsorship deal with Gazprom, the Russian energy giant, reportedly for two years and $50 million.

The IOC, which suspended the federation in 2019, has publicly said the federation was in the hole to the tune of at least $16 million. The IBA says it was more like $20 million.

Kremlev and the IBA inherited this massive debt from the prior regime, when IBA was called AIBA and the president was former IOC executive board member CK Wu of Chinese Taipei. Wu’s idea was to launch a semi-professional league called the World Series of Boxing. It bombed.

Wu, an IOC member since 1988, ran for the IOC presidency in 2013 but did not come close in the contest that saw Bach take office.

Bach, re-elected in 2021, is president until 2025. To highlight Wu’s many years as an IOC insider: an architect, Wu was the driving force behind the 2013 opening of a museum in Tianjin, China, dedicated to Juan Antonio Samaranch, IOC president from 1980 to 2001; Samaranch, who is still revered within IOC circles, donated to Wu his lifelong Olympic collection, some 16,000 pieces, for display at the museum.

Two supremely logical questions. 1/ If you were Kremlev, when you took over, what would you do to get yourself out of a massive financial hole? 2/ And wouldn’t you ask, why are we in this situation?

In May 2019, a three-person IOC member panel conducted an “inquiry,” taking special note that its mandate was “not to look into the situation of individuals but to assess [the federation’s] governance.” It observed that one 2018 report produced by an outside firm “did not provide any evidence of illegal behavior committed by Mr. Ching-Kuo Wu.” Even so, the three-person IOC panel suggested that the IOC’s chief ethics officer — who had been involved all along in that self-styled “inquiry” — ought to “evaluate” any information related to him.

Noteworthy about this inquiry panel is who was on it: Nenad Lalovic of Serbia, a shrewd businessman; Richard Carrion of Puerto Rico, one of the world’s leading bankers; and Emma Terho of Finland, current chair of the athletes’ commission, with a background in economics and banking.

IOC documents nearly always speak in code, and these three were clearly suggesting something was amiss. They also said that outside report had signaled the federation’s fiscal problems were the “series of poor decisions directed by the former president” that led to projects that were “substantial cash drains on the association.”

A quick timeline review:

- 2018 outside report notes “poor decisions” but provides no evidence of illegality

- May 2019 IOC report from three-person inquiry

In March 2020, the IOC put out a statement: it was accepting “with great respect” Wu’s resignation as IOC member. He was resigning, it said, “following medical advice.” The IOC further expressed its “thanks and respect” for his 30 years of contribution to the movement.

Did anyone notice? That statement went out March 17. The sports world had all but stopped on March 12, the dominos tumbling when Rudy Gobert of the NBA’s Utah Jazz tested positive for COVID-19.

What needed to come to light was a full account of the “poor decisions” during the Wu years. Enter McLaren.

Timeline, again:

In June 2021, the IBA, under Kremlev – not the IOC – commissioned McLaren to find out what had happened.

Canada’s Richard McLaren at September 2021 boxing-related news conference // Getty Images

McLaren has been the go-to for many within the Olympic scene seeking a forensic look at why things go wrong.

In a series of reports, he made recommendations for, among other things, an independent integrity unit; a whistleblower policy; and, perhaps key, an overhaul of field-of-play policies, those protocols then to be “rigorously enforced.”

It says here that what would also be appropriate — this is basic governance — would be an independent audit of IBA finance. In the interests of transparency, it would significantly enhance credibility, too, for host-city contracts and their financing arrangements to be made public. Plus, the details by which — how and when — athletes get paid.

On Saturday, as a “goodwill gesture” amid the tension with the IOC, the IBA said European boxers, technical officials and coaches had the OK to “freely participate” in next month’s European Games, a Paris 2024 qualifier. The IBA also said it reached out to McLaren to interface with the IOC to help pick referees and judges, and offered its new technologies — at IBA competitions, per McLaren, the draw and scoring are run not by IBA but by “employees of Swiss Timing.” Notably, the IBA release also reiterating “its desire for cooperation as we work to regain our Olympic recognition,” said it had reached out to a potential interlocutor, Spyros Capralos, an IOC member from Greece and also president of the European Olympic Committees.

McLaren’s overarching theme is not just that IBA practices and procedures, like those above, needed to change. Its culture needed a thorough revamp. Because, he said, under Wu the federation had almost done itself in.

His key report was issued June 20, 2022. In it, he proved unsparing:

“The responsibility of this near collapse falls on the management of AIBA [now IBA] along with president Wu. The president’s contribution was keeping the executive committee (EC) completely ill-informed and misrepresenting what was going on financially within AIBA as a result of the marketing catastrophe of WSB. Contracts were signed by him without EC deliberation or approval. Eventually, when the strain on the organization became such that Wu could no longer hide the financial reality, the EC demanded an audit.”

Wu, he said, bore ultimate responsibility: “Behind both [executive directors] the ultimate controller of events was the president who meddled in all matters but took no responsibility for the execution of the sport, always leaving it open to blame the [directors] or others.” [Emphasis in the original]

Some of the details in the June 20, 2022, report are truly breathtaking. All the same, whether because of bias or complexity or other reasons, little to none of it has been reported. A reasonable question, too, is why no prosecutor has seized on these facts:

Wu won election as AIBA president in 2006 as a purported reformer, taking over from Anwar Chowdhry of Pakistan. Now, McLaren reported, it turns out “the election was not without drama,” it appearing “both candidates used cash bribes to obtain … votes.”

Wu “allegedly made a deal” with Gafur Rakhimov, typically described in news accounts as an Uzbek businessman. The U.S. Department of Treasury had him on a sanctions list, saying he was a key member of a criminal gang that oversaw heroin trafficking operations in Asia. In 2021, Rakhimov sought to have his name removed from the list. He did not prevail.

“Ensuring that his AIBA platform remained untarnished was necessary, as it was the launching pad for [Wu’s] bid for the IOC presidency.” In 2013, Bach, not Wu, won the IOC top job.

From the start, McLaren said, Wu and Rakhimov had a deal: Wu would resign the AIBA job after two terms, in 2014. This would enable Rakhimov, then an AIBA vice president, to run for the top job. Wu reneged. He stayed on until stepping down in 2017.

CK Wu at AIBA (now IBA) offices in Lausanne in 2017 // Getty Images

As for the World Series of Boxing: “Wu entrusted the administration and financial planning of the WSB American Operations to Abe Lin (a Chinese citizen from Taiwan then resident in the USA), a childhood friend that Wu instructed to be hired, despite the fact that he was the subject of a criminal investigation into allegations that he was trading in state secrets during his time in the Taiwanese military. It seems to be the case that Lin reported privately and exclusively to Wu on the state of [World Series of Boxing] finances and operations in the Americas. As of 2017, he was still under contract to AIBA as a financial consultant. The [report] concludes that the cronyism here exacerbated an already less than optimal business administration plan and execution. Indeed, many witnesses advised the [report] that Lin was incompetent and unable to perform the role required to launch and sustain the WSB vision. This incompetence spread to him being unable to keep complete records and ultimately being unable to account for the significant funds he had been sent and was using to finance the WSB [American operations].”

Another friend, Di Wu, became a multimillion-dollar investor in what was to be the WSB’s marketing and promotional agency, and “as an unofficial thank you … was made an executive vice president” of the federation …” with “access to [its] inner workings.”

Financially, AIBA “was a house of cards consistently on the verge of collapsing until another investor would come along and stabilize it, albeit momentarily. As a result, for nearly a decade AIBA hovered precariously on the line between solvency and insolvency. This state of affairs only changed with financing provided by Gazprom in 2021. Whatever the debate about the source of funds, exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there is no doubt that the Gazprom sponsorship has saved AIBA and helped the organization onto a solid financial footing.” [Emphasis added.]

By 2019, “the office shrank to a single person … due to Wu’s corrupt financial legacy.”

In June 2019, no one batted an eye when, with Rakhimov involved, the IOC leveled its suspension. He was replaced in July 2019 by Mohamed Moustahsane of Morocco. McLaren’s report describes him as a “puppet interim president.”

Just to make matters clear:

“Following the election of President Kremlev the precarious legacy of Wu has been put to the past.”

And:

“… the catastrophic state of AIBA finances described above is now a legacy of the Wu presidency. The financial input by Gazprom put an end to the jeopardy that AIBA put itself in and saved it from financial collapse.”

There can be little question that any controversy over Gazprom money is simply that it’s Russian.

Gazprom sponsored UEFA. It sponsored the soccer team Schalke 04 in the German Bundesliga. When the war in Ukraine started, these sponsorships abruptly went away.

The IBA deal did not. But how could it?

The IOC pays out to the various federations — there are 28 considered ‘core’ federations — varying sums over the four-year period, called a quadrennium, or quad, between a Games. How much depends on a sport’s popularity and other factors. Track and field gets the most; for the four years 2021-24, it is due $39.48 million. Golf, rugby and modern pentathlon get the least, $12.98 million. Boxing’s take, again spread over four years: $17.31 million.

Revenue distribution to the Summer Games sports for the Tokyo ‘quad’

Because IBA is suspended, it isn’t seeing even a penny of that.

This is where the IOC put IBA between the proverbial rock and hard place. What, exactly, was IBA supposed to do with millions of debt? Reach out to other sponsors? That’s basic economics.

The British and Americans, in particular, now complaining long and loud about Kremlev? Where were they in 2020 to exert financial pressure on their corporate entities to secure, say, $50 million? That didn’t happen? Why not?

Meantime, it should be noted that when the pandemic all but brought the world to a halt, in 2020, the IOC made available at least $63 million in loans to a variety of international federations facing “financial hardships” due to the cancellation of events. IFs that got IOC loans included basketball, gymnastics, swimming, tennis, track and field, rowing and more.

Boxing? Not a dollar.

At that news conference in Tashkent before the boxing itself got underway, the IBA said the Gazprom deal had run its course, ending in December 2022.

The IBA fiscal year runs July 1-June 30. George Yerolimpos, the IBA secretary general, said in an interview that for the current year — that is, ending June 30 — IBA’s annual budget is roughly $17 million. For the year starting July 1, projections are that it will be at least $30 million, he said.

He also said a deal with adidas is in the works along with one with sports equipment maker Sting.

Ten “big names in the sports industry” are coming on board, he also said.

“As of today,” Kremlev said at the news conference, “we have plenty of other companies sponsoring us.”

—

Bach understands financial stability. He talks about it time and again. Indeed, again last October, speaking to the Assn. of National Olympic Committees at a meeting in Seoul, he said, “In this fragile world, the stability that we are enjoying is perhaps the strongest currency that you can have.”

You might think an international federation that achieved financial stability in the midst of a global pandemic might warrant not only favorable attention but considerable interest from peer federations themselves unsettled in our “fragile” world about how they, too, might achieve fiscal fortitude.

But no.

The reason why that hasn’t happened is elemental: the Gazprom money is Russian.

With Gazprom now out of the picture, that, in theory, would seem to remove one of the IOC’s key objections to current IBA operations.

The sports world has been only too happy to take cash from anywhere and everywhere else. See LIV Golf — Brooks Koepka on Sunday becoming the first member of the breakaway tour backed by the Saudi sovereign wealth fund to win a major title, the PGA Championship. As the tennis entity WTA’s recently announced return to China after months of protests over the case of Peng Shuai makes plain, it’s always about the money.

A few of the IFs are self-sustaining entities: basketball, tennis, soccer and some others.

The vast majority of the 28 core sports, however, are heavily financially reliant on the IOC.

In turn, the IOC is heavily dependent on U.S. television revenue. The NBC deal ends in 2032. Almost the very first thing Bach did when he took office was extend the deal, to ensure the IOC’s “stability.”

Since that deal was struck, in 2014, the television marketplace has changed considerably. Among other things, this is why the next IOC president — the election is two years away — must be someone with extensive experience in the rough and tumble of international business.

At any rate, looking ahead, it’s far from clear how long the IOC-to-the-federations gravy train, subsidized by American TV cash, can continue. So, again, one might think that other federations might be looking over at the IBA and going, wow, they got themselves more than upright again — and in a pandemic? Without a dollar from the IOC? Hey, how could we do that, too?

George Yerolimpos, IBA secretary general, at the Tashkent news conference

“We are the experiment,” Yerolimpos said. “We are looking at the operation a different way. We believe we are doing a real revolution.”

What does that leave?

These options:

One, they’re after Kremlev because of Kremlev himself.

Two, they’re after boxing itself.

Three, both.

To the facts, please.

—

For nearly two generations, some 35 years, under three successive presidents, Samaranch to Jacques Rogge to Bach, the IOC has been squeezing boxing’s place on the Olympic program.

The numbers, per the authoritative website Olympedia, make this more than plain:

1988 432 of 8453 — 5.1%

1992 336 of 9386 — 3.6%

1996 355 of 10339 — 3.4%

2000 307 of 10647 — 2.88%

2004 280 of 10557 — 2.65%

2008 283 of 10899 — 2.59%

2012 283 of 10518 — 2.69% — first female boxers at Games 247 male / 36 female

2016 283 of 11180 — 2.53% — 247 male / 36 female

2020 289 of 11319 — 2.55% — 187 male /102 female

2024 248 of 10500 — 2.36% — 124 male /124 female

In 1988 in Seoul, the program featured 23 sports. Only four sent more athletes than boxing: track and field (1618), swimming (633), rowing (593) and cycling (436).

By 2020 in Tokyo, the program had expanded to 33 sports. Now 15 sent more athletes, and two sent almost as many as boxing’s 289. That 289, incidentally, marked a jump of six from the 283 seen at the prior three editions, up nine from 280 in Athens in 2004.

But against the leap in other sports, that marginal rise was essentially meaningless: essentially half of the sports on the Olympic program, 17, 15 + 2, sent more or as many athletes as did boxing.

The 15: rugby sevens 311, gymnastics 324 (196 artistic + 96 rhythmic + 32 trampoline), canoe 330 (82 slalom + 248 sprint), basketball 349 (284 + 64 3x3), sailing 350, shooting 355, handball 365, judo 388, volleyball 380 (286 + 94 beach), field hockey 422, rowing 523, soccer 524, cycling 534 (18 BMX free + 48 BMX race + 76 mtn bike + 199 road+ 193 track), swimming 926 (875 = 51 open water), track and field 1913.

The two: water polo 286, wrestling 287 — and note that if boxing had been stuck at 283 as in 2008, 2012 and 2016, these two sports would also have sent more athletes.

In 2024, the call is for boxing to have 248 quota slots. That’s out of a total of 10,500 athletes. That figures out to 2.36%, the lowest percentage yet for boxing at the Games.

That 10,500 figure is probably meaningless, because it is a target. The IOC almost always goes over. If the real figure ends up being more like a real-world 11,000, then the percentage drops even lower … to 2.25%.

These numbers make crystal clear why Kremlev and Yerolimpos, at the Tashkent news conference, said boxing and boxers, through the IBA — as much as they love the Olympics — need to look out for boxing and boxers.

“The Olympics,” Yerolimpos said, “is a very nice and beautiful tree. We would like to be close to it. However, the IBA would like at the same time to also deal with other trees as we need to take care of the whole forest of our athletes and of our member [national federations].”

With, you know, money.

—

If the topic is boxing and the Olympics, this is where what is for now the World Boxing matter must be addressed.

To reiterate, McLaren in December — “IBA is changing significantly.”

Nonetheless, on April 13, a group of federations including the United States and Great Britain announced they were forming World Boxing and would seek IOC recognition. The announcement said it would be led by an interim board from organizations in Britain, the United States, Germany, Holland, New Zealand, the Philippines and Sweden.

“I think we all know that it’s time for a change,” USA Boxing president Tyson Lee told reporters on a Zoom call. “Or at least it’s time for another option — an option that prioritizes the Olympic movement.”

Boris van der Vorst of Holland is part of this effort. When he says World Boxing represents a “coming together of people whose interest is solely in creating a better future for boxers and ensuring the sport continues to be a major part of the Olympic Games,” one, has he looked at those numbers showing the decline from 1988, and, two, don’t boxers already — with major IBA paydays, better than track or swim stars — already have a bright future?

Van der Vorst ran against Kremlev for the IBA presidency in December 2020. He lost. He put himself forward again as a candidate in May 2022 but was declared ineligible. Kremlev was elected, again, this time to a full four-year term. The next month, the Court of Arbitration for Sport ruled van der Vorst should have been eligible. In September, the IBA Congress, however, opted not to hold another election on the grounds it already had held two in two years and a third would change nothing.

Amid all of this, meanwhile, van der Vorst ran in April 2022 for the presidency of the European boxing organization, which goes by the acronym EUBC. He lost, to Ioannis Filippatos of Greece.

That’s three elections and … three losses.

In a May 8 tweet, Van der Vorst asserted, among other things, referring to the IBA, “Sports journalists are now feeling the effects of the oppressive regime,” and some unsolicited advice on this count — bringing us into the convo, as if that’s going to be a decider, has rarely proven a winning argument.

World Boxing’s listed address is in Renens, Switzerland, near Lausanne. Public records, easily accessible on the internet, show that address is interim general secretary Simon Toulson’s home.

World Boxing says it is based on five principles: boxing at the heart of the Olympics, ensuring the interests of boxers are first, deliver sporting integrity and fair competitions, creating a competition structure in the best interest of boxers, operate according to the strongest governance standards and transparent financial management.

If you are a boxer from Country A, where in that manifesto does it say, I can earn money? Say, $200,000 if I win? Or $400,000 next year? Or a cool $1 million in 2027?

World Boxing launched, it said, with $900,000. It has not detailed where — sources and amounts — that $900,000 came from. Is that “transparent financial management”?

Mike McAtee, USA Boxing’s executive director, said the $900,000 “will come from value in kind (VIK) donations, corporate sponsorships, membership fees, seeding funding, grants and loans.”

World Boxing’s strategy would seem transparent, however: survive until the IOC assembly this October in India, figure out a way to get the IBA thrown out for good, rush the process to get provisionally certified — which would normally take years —and then have its senior leadership get their paws on the $17.31 million due the IBA.

It’s also abundantly clear to anyone with an ounce of common sense that this road is the direct highway to a lengthy lawsuit that presumably would only tie things up even longer.

It’s also equally clear that some believe the fix may – stress, may – be in. Get the IBA thrown out? Rush the process? Would World Boxing have launched unless someone somewhere had assurance those things were likely to happen? Toulson worked years ago at the IOC. Coincidence?

Then again, if this is a governance and business proposition, let’s talk – business.

USA Boxing has not produced a men’s gold medalist in 20 years, since Andre Ward in 2004. Claressa Shields won golds in 2012 and 2016. (Three U.S. boxers won silver medals in Tokyo; Oshae Jones won a women’s welterweight bronze; those four medals marked the best U.S. performance since the Sydney 2000 Games.)

Moreover, if there is one city in the United States that is synonymous with boxing, you would think it would be Las Vegas — indeed, while we’re on the common sense train, that’s where it should be in 2028 for the LA Games.

For USA Boxing, though, Las Vegas is hardly — if you will — the Emerald City. McAtee said the federation’s members “want to see boxing,” adding, “They don’t want to go gambling.”

The view from Colorado Springs, Colorado, where it is based, is that USA Boxing is first and foremost a service-driven organization. Yes, Olympic medals are the top of what it does. But, McAtee said, so much more.

“Look, being in the Olympic movement is our No. 1 priority. That said, we have 38,000 boxers in the United States. That’s membership-wise,” he said. “Thirteen will have the opportunity to qualify to go to the Olympic Games, seven men and six women,” the Paris 2024 categories.

“About 10% will turn professional, of the ones over 18. So, you’re looking at 200 boxers. About 100 aren’t really good enough but do, anyway. What does USA Boxing do? We focus on the people who don’t turn professional, who don’t go to the Olympic Games, but go on to be citizens. That is our mission.”

He added, “The mission of USA Boxing is to win medals at the highest level, yes, but also to help effect positive change and save lives. It’s not just the boxers. It’s the coaches and officials.

“To help them be the best schoolteacher, journalist, cop, soldier, firefighter — whatever you do in life. Very few reach the top athletically. We want to change the lives of kids in neighborhoods. We want to help teach delayed gratification, self-respect, discipline and treating others with respect.”

To be gentle, because it would later absorb a direct hit from Hurricane Laura, Lake Charles, Louisiana, where USA Boxing held its 2020 Trials, is not a major American metroplex. But, as McAtee said, in Lake Charles, USA Boxing was “a big deal” and for its members the prices were right.

The 2024 Trials are due to be held in Lafayette, Louisiana. If you’re planning, Lafayette is two hours closer than Lake Charles along Interstate 10 to New Orleans.

Two weeks after the World Boxing announcement, USA Boxing resigned from IBA. In the month since the World Boxing declaration, no other national federation has likewise broken away.

“At the end of the day,” McAtee asserted, “I have to know that if I’m going to send boxers to compete, I’m not going to send them to compete when I know there is corruption and they’re not going to get a fair shake. I’m not going to do that. That’s why we left, to do that. That’s why the competition is now being run by IOC.

“Why,” he asked, “be part of an organization you know is corrupt?”

In early May, USA Boxing sent a team to an event in the Czech Republic. This prompted boxers from three nations — Brazil, France and Poland — to depart. The Americans interpreted the eligibility rules for the event one way. Was it their place to potentially — emphasis, potentially — put the many other nations at risk? Or was this just classic American behavior: deciding what was best for Americans in a big world?

More to the point, and again — money.

USA Boxing’s most recent tax return, for the year 2021, indicates it took in all of $39,081 in sponsorship dollars.

Total. $39,081. For the year. An Olympic year.

From USA Boxing’s 2021 tax return

In the greatest sports marketplace in the world, where 30 seconds of TV time this February for the Super Bowl cost $7 million, the country that produced Muhammad Ali, Sugar Ray Leonard, Oscar de la Hoya and more — $39,081?

Being generous: its 2021 auditors report lists $182,916 in “sponsorship and marketing.” The difference: VIK, value in kind.

Compare: on its 2021 tax return, USA Track & Field reported $20.2 million in “sponsorships and royalties.”

The auditors’ notes — this is deep into the file — show that USA Boxing has, since 2009, owed the USA Amateur Boxing Foundation $1.795 million. Why? The year before, per the federation, then-leadership misappropriated funds. Each year, USA Boxing pays the foundation $100,000. It paid the 2022 payment last year and the 2023 payment earlier this year. A positive for USA Boxing: the note bears no interest.

That $39,081 was way up, meanwhile, from the $7,042 in corporate sponsorships USA Boxing reported on its 2020 tax return (a COVID year); on par with the $35,362 on the 2019 return; but down markedly from the $67,566 on the 2018 form, $86,084 on the 2017 return and, the last Olympic year before Tokyo, $51,920 on the 2016 form, the Rio Games year.

McAtee took over as executive director in 2016. His position is that USA Boxing has been through some rough years and is now, just now, especially coming out of COVID, in the best spot it has been in a long while. Membership numbers: up, to more than 50,000. Livestream numbers: markedly up. Some 2400 gyms around the country.

To suggest that USA Boxing is in competition with the NFL or, for that matter, the UFC for those kinds of big-time entertainment sponsor dollars — that’s not, he said, realistic. USA Boxing, he stressed, is a nonprofit.

“We have,” he said, “a viable product.” He said sponsors and CSR — corporate social responsibility — executives increasingly see the value in boxing and boxers, and said the organization is “getting ready to put out a press release for some corporate sponsor opportunities.”

He also said, “We are pivoting,” adding, “We are making inroads.”

—

When Bach was in China a few days ago, it was of considerable significance that he met with Li Qiang, the premier.

To be clear, the IOC president holds a unique place among world personalities, and particularly this president, who has made a point to emphasize the IOC’s special status as a bridge-builder. In January 2022, who was the first foreign dignitary Xi would receive since the pandemic had begun two years before? Bach. Last November, Bach was invited to speak at the G20 Summit in Bali. There, he said, “Olympic sport needs the participation of all athletes who accept the rules, even and especially if their countries are in confrontation or at war.”

To compare the IOC president with the president of an international sports federation is classic apples and oranges.

All the same, when Kremlev was in China late last month, here is how he was greeted at the Shaolin Monastery — by 20,000 people.

In China, such gatherings only happen because the government — that same government — makes them happen.

This greeting, and the signaling of what it took to arrange it and who it was for, should be well understood. This was akin to a state visit.

Within the IBA, it’s not a mystery why Kremlev was elected and then re-elected.

Almost no one in the Western press notices this sort of thing, however.

On the surface, you wonder whether Kremlev wouldn’t be the sort of IF president the IOC might want to embrace. Younger, articulate, just as happy in a hoodie and sweats as a suit, social media-savvy. How many IF presidents feed almost religiously to their Instagram feeds the way Kremlev does?

With China and Russia expressing solidarity in many ways, ways that would seem super-obvious to anyone assessing the state of boxing in the Olympic landscape, it would thus also seem manifestly plain to return to a familiar adage that Samaranch used all the time — keep your friends close and your enemies closer.

Why, then, the distance between Kremlev and the IOC?

Since Kremlev was elected in December 2020, he said he has not had even one formal meeting with the IOC. It’s not for trying on his side, he said. By chance, he ran into Bach and IOC sports director Kit McConnell at a 2022 conference and, he said, McConnell told him, “We like so much the way you are writing to us.”

Is it then that the IOC doesn’t like, respect, trust Kremlev? Yes, yes, yes, no, what? There is much the world does not know about the way the Russians have tried IOC patience. Is it that, combined with the basic that he’s Russian at a time in our world when the IOC has looked the other way too often when it comes to Russian behavior and with Kremlev they have decided to draw the line? Did he simply get too Russian too fast? Yes? No? What?

“Look at me. I am an open book,” Kremlev said in an interview. “My personal life is there 24/7. Everything I do. Everything is public. There are no secrets. I don’t hide anything from everyone.”

That letter the IOC has since November 2021 had in its files provides answers to several lines of questions about him that have been raised.

His last name:

“When my father was a child, he was adopted by a man with the surname Lutfuloev, who just after two years abandoned my father and returned him to a foster home. As you can imagine, that surname did not bear the happiest of memories for my father and he always wanted to learn more about his birth parents. Later in life, my father changed his name to one from his family line. When I got older, I also investigated my family’s past and came to know that Kremlev was an authentic part of my mother’s lineage. And with full support of my family I changed my previous surname to this new one.

“I would also like to note that my wife’s maiden name is ’Shcharenskaya,’ which once again proves that statements in the public domain assuming that I took the surname ‘Kremlev’ from my wife are false …’

Allegations of a criminal past:

“… these were also made to the independent AIBA Ethics Commission … often these sources are simply online news articles that have been maliciously created.”

The letter goes on to note that one such — false, he said — story was replaced in an outlet called Soviet Sport with this story, a lengthy Q&A.

Question: “Have you been prosecuted? Information was actively circulating that you allegedly have two convictions, for extortion and beating, is this true?”

Answer: “Documents speak best of all words. I can demonstrate an official certificate of non-conviction, which, I hope, will remove all questions.”

This is that document, certified in Russia and, as well, notarized in Switzerland for the benefit of the IOC.

The official document sent to the IOC purporting to show that Kremlev has no criminal convictions in Russia

The November 2021 letter goes on:

“I understand there is a certain perception in the West of successful Russian businessmen and am happy to clarify my own business dealings …”

Kremlev said he initially was in the construction business, at the time of a huge construction boom in Russia, “so I soon went from building just roads to also building houses and supplying materials.” He tried other ventures, including a gold factory but that closed after two years, he said.

At the time of the writing of the letter, Kremlev said, he was 51% owner of an LLC that runs Russian state lotteries, an entity regulated by the state ministry of finance.

Kremlev’s position is that he is not, repeat not, a state official but very much a private citizen. Lottery proceeds, he said in the letter, help fund the development of sports in Russia, “including activities for the development and popularization of physical culture and sports, elite sports and the training system for the next generation.”

And there — right there, in his own words — is ample reason for the IOC to keep its distance.

To be fair, not in November 2021, when the letter was written.

But assuredly since February 2022, if money from the lottery is underwriting Russian “elite sport.” This term is usually understood to mean Olympic or high-performance sport.

Or perhaps it’s not ample reason. Maybe it’s simply an opportunity for clarification. Or negotiation.

The IBA position is the IOC should at least say why they can’t get an audience. It’s not only Kremlev. Yerolimpos is a well-known personality in Olympic circles. He lives in Lausanne. He and McConnell have known each other for years. A few days ago, the IBA sent the IOC a 400-page document detailing its position on reform: “This is real change,” Yerolimpos said.

Yerolimpos said, referring to McConnell, “I like the guy. We have a very good relationship. He likes me also. He knows I will make a deal.”

He said, “Certainly smart people can find a smart solution. It doesn’t exist an obligation to be 50-50 this solution. Me, I’m not playing this game. They want the prestige,” meaning the IOC, “OK, they have it.”

But, Yerolimpos said, “This is my expression: if you want to dance, it takes two persons.”

Kremlev said, “All we need to do is meet and get a road map,” adding that in more or less the time it takes to watch Rocky Balboa, who then and now could teach us all a lot about détente, so why not the IBA and IOC, “We can resolve this in two hours.”