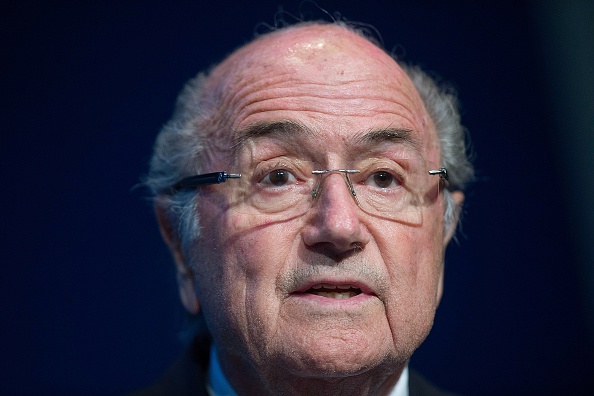

Way back when in journalism school at Northwestern, they taught us to be entirely skeptical about a great many things. The lesson they taught us in Evanston went like this: if your mother says she loves you, check it out. This maxim comes to mind now in assessing the state of soccer’s world governing body, FIFA, and in particular the status of its president, Sepp Blatter. Thousands upon thousands of words have been written since he purported earlier this month to be resigning. Yet among all those words, perhaps the most relevant seem to be missing amid that “resignation”: a resignation letter.

It’s axiomatic that a genuine resignation leads to the execution of such a document. Has one surfaced?

Curious.

Or, perhaps, not really, not if you believe that Blatter never had any intention of resigning and, all along, his “resignation” has been the first step in an elaborate dance that he concocted to buy time.

And why not?

After all, he got 133 votes in that election on May 29.

Who then can really be surprised at reports this week that maybe, just maybe, Blatter might not really be out the door?

To be clear, and for maximum emphasis: allegations of systemic corruption have shadowed FIFA for years, and now the time would seem to be upon it for change. But simply shouting, over and over, loud and louder, for Blatter’s head, is not necessarily in and of itself change.

A journalistic mob brandishing the digital equivalent of pitchforks and torches is not helpful. It might feel swell to be part of the mob. But it’s empty.

The serious questions that need to be asked are these: what kind of hard change needs to be effected, and who are the right people to effect that change?

A few years after journalism school, I went to law school, to the University of California’s branch in San Francisco. I graduated and even (first try!) passed the California bar exam. Maybe, over the years, I have proven to be a better journalist than a lawyer. But along the way I did manage to pick up a few lawyering tips. Here’s one:

The rules matter.

At the San Francisco law firm where I worked after graduation, a senior partner once advised that it was a good idea at the start of each calendar year to review the particular statutes of each and every area of what lawyers like to call “subject-matter jurisdiction.”

To make it easy, in the case of FIFA the relevant statutes at issue are Articles 22 to 24.

Article 24 lays out who can be a candidate for president. Blatter knows this one well.

Article 23 details the one-country, one-vote rule that is so essential to the 209-member FIFA system, and that assuredly has to be a focus of the moment for reformers and conservatives alike.

It’s already common knowledge in international sport circles that Michel Platini, the UEFA president, met last week in Lausanne, Switzerland, the International Olympic Committee's base, with Kuwait’s Sheikh Ahmad al-Fahad al-Sabah, the president of the Assn. of National Olympic Committees and, as well, a new member of FIFA’s executive committee, which in soccer circles is commonly called the ExCo. All anyone had to do was be at the plaza bar at the Beau Rivage hotel to see what was what.

Platini’s name keeps getting floated as a Blatter successor, as if Europe is somehow entitled to get its way next, again, after 17 years of the Swiss Blatter. The sheikh, meanwhile, who has a way of making things happen in whatever arena he plays in, has been mentioned as a potential successor as well, even though he is likely far more interested in ANOC, and in particular the promise of a Beach Games project.

At any rate, for Blatter’s purposes going forward, it is Article 22 that is most essential.

In theory, that would be as a predicate to revisiting Article 24.

The issue is, how does Article 22 relate in practice to Article 24?

Because it would appear there's a serious disconnect.

Recall that on June 2, when he said he was resigning, Blatter said he was calling for an extraordinary congress. Or, maybe, he was calling on the ExCo to set up such a congress.

The distinction is rather important.

Here was Blatter at the news conference that day: “Therefore, I ask to convene an extraordinary congress as soon as possible.”

Here was Blatter in the same-day news release from FIFA: “The next ordinary FIFA Congress will take place on 13 May 2016 in Mexico City. This would create unnecessary delay and I will urge the Executive Committee to organize an Extraordinary Congress for the election of my successor at the earliest opportunity.”

According to multiple reports, including the BBC, FIFA appears inclined to schedule the extraordinary congress for Dec. 16 in Zurich. An ExCo meeting, at which the date of the congress would obviously be high on the agenda, is set for July 20.

Back to the rules.

Article 22 says clearly that the ExCo may convene an Extraordinary Congress “at any time.”

But not at the president’s request.

Only if “one-fifth of the members make such a request in writing.”

One-fifth of 209 is 41.8.

Thus 41 or 42 nations, depending on whether you’re rounding up or down, have to ask — in writing — for an extraordinary congress.

In an era of purported transparency and ferocious interest in its business, doesn’t FIFA owe it to the world to make public the list of the nations requesting this extraordinary congress?

Next:

“An Extraordinary Congress shall be held within three months of receipt of the request.”

The ExCo meeting is scheduled for July 20.

Three months past July takes the calendar to, at the latest, October.

Further complicating matters, a FIFA statement issued June 11 — announcing that July 20 ExCo meeting — said, “During the meeting, the agenda for the elective Congress will be finalized and approved. The extraordinary elective Congress will take place in Zurich between December 2015 and February 2016 as announced by the FIFA president on 2 June 2015.”

So what’s going on?

Dec. 16? When the rules clearly say three months max after, in this instance, July 20?

Here’s a theory, with several layers:

There’s going to be a fall guy, for sure, and despite the rush to judgment in the mainstream press — in the United States, in Latin America and in western Europe — who is to say it’s going to be Blatter?

As for Blatter himself being a “focus” of the Justice Department case: Blatter presumably learned after the ISL mess some years ago not to leave his fingerprints on anything substantive.

And as for that DOJ case:

Any evidence that Chuck Blazer might have to offer might well have to be submitted by deposition because by the time these cases make it to trial Mr. Blazer might or might not still be with us on this earthly coil. Feel free to ask a more experienced lawyer than me whether such evidence is in the first instance admissible in federal court or, next, liable to amount to a winning strategy.

As for Jack Warner — again, ask a more experienced lawyer whether he or she would relish the opportunity to cut Mr. Warner up on cross-examination. The very first item would be Mr. Warner’s video brandishing The Onion, the satirical newspaper, and let’s take it from there.

If one reads the FIFA website carefully, one would have noted on June 4, just two days after his “resignation,” a release touted Blatter’s proclamation that meaningful reform was already underway.

So, again, why Dec. 16?

Recall that the Swiss authorities have launched their own investigation into FIFA’s affairs.

In these sorts of things, June to December can be a long, long time.

What if, say, by December, that Swiss inquiry turns up nothing of significance?

You don’t think so? The European legal system can be very different than the American. The U.S. system, for instance, is premised on plea-bargaining, and such deals are typically used to pressure those caught in the system to sing in an effort to nail those higher up; it often doesn’t work that way in Europe, where singing is thought to be a means of inventing. Also, the emphasis in Europe is typically in “keeping your collective nose out of other nations’ legal affairs,” according to a quote to be found in no less than the Economist, which assuredly has been zealous in its anti-Blatter reporting.

If Blatter gets a free pass or its equivalent from the Swiss inquiry, he would then be able to appear before the extraordinary congress and say, 133 of you voted for me in the spring — would you like me to continue my mandate?

Who’s to say the members wouldn’t — in December, just nine days before Christmas — be feeling the holiday spirit?

Fanciful?

Really? Any more than winning re-election just days after the U.S. indictments themselves?

Remember, some 15 years ago Juan Antonio Samaranch led the IOC through the Salt Lake City scandal.

Don’t fall into the “Samaranch was a fascist loser” trap that is the trope among many on the outside looking in. Within the IOC, Samaranch was, and remains, revered. The issue is, how within FIFA is Blatter viewed?

The answer is pretty obvious: 133 votes from the delegates. And that widely reported standing ovation from the staff.

To those who insist soccer needs an outsider: recall the U.S. Olympic Committee’s experience roughly six years ago with Stephanie Streeter as chief executive. It simply did not work. She and it proved a bad fit, and anyone who would come in from outside to try to run FIFA almost surely would prove the same, and for the same reason — culture. You have to know soccer to run soccer.

You can like it or not. But you can almost hear Blatter saying just that, can’t you?

Of course, maybe FIFA is, actually, committed to fantastic reform.

Back to the future: Sepp Blatter said June 2 he is resigning. Do you believe him?