The U.S. Department of Justice on Tuesday flipped a big, fat middle finger to the international sports movement.

On what grounds? And to achieve, exactly, what?

Did anyone at the U.S. Attorney’s office in Brooklyn stop for even a second to think about the consequence — to the Los Angeles 2024 Summer Games bid, to the possibility of an American World Cup men's soccer tourney bid for 2026, to the interests of U.S. athletes everywhere — in opening a criminal investigation into allegations of state-sponsored Russian doping?

It is very, very difficult to make even — a little law talk here — a scintilla of sense from what, at first impression, seems like nothing so much as an outrageous, politically driven abuse of prosecutorial and law enforcement discretion.

In the United States, the law does not criminalize sports doping.

Italy, just to pick one — sure. But not the United States.

Yet here come the feds, reportedly launching a criminal investigation into sports doping. By athletes who are not Americans. What?

Indeed, as the New York Times first reported, the Department of Justice, through that Brooklyn prosecutor’s office, is “scrutinizing Russian government officials, athletes, coaches, anti-doping authorities and anyone who might have benefitted unfairly from a doping regime.”

It said the investigation “originated” with the FBI.

Because there isn’t a specific doping-related statute in U.S. law, federal prosecutors are apparently eyeing fraud and conspiracy charges, the Times reported.

This is, at best, legal gymnastics.

Moreover:

Imagine if the Russians, or the Chinese, or the French, pick anyone anywhere, decided to go after Americans: accusing U.S. athletes or their entourage or even American government officials of a crime under that particular nation's laws, basing the whole thing on allegations of sports-related doping.

What would the reaction be?

How is this any different?

The United States is not the world’s police officer nor, hardly, its prosecutor, judge and jury.

Who in the confines of some office in Brooklyn thought otherwise would serve any sort of American interest in our complicated, nuanced world?

News of the action from that U.S. Attorney’s office came as the International Olympic Committee announced Tuesday that re-tests of samples from the 2008 Beijing Games had turned up 31 positives, IOC president Thomas Bach calling it a “powerful strike against the cheats.”

Backing up for a moment:

You have to be a complete idiot to get caught doping at the Olympic Games. Everyone knows the authorities are going to be testing. And that samples get saved for years.

So there are two options here:

One, officials finally managed to get, say, some top-level Jamaicans or Kenyans. That would be a “powerful strike.”

Two, and more likely, if this cast of 31 was a Kevin Spacey movie, it would be the usual suspects. There are roughly 10,000 athletes at a Summer Games. Catching 31 means roughly 0.3 percent. Whoo.

Let’s be clear:

In this moment, the IOC is facing a potentially unprecedented onslaught of challenges: everything from Russian doping to the seemingly chaotic preparations for the Rio Games, from allegations of potential bribery involving Tokyo’s win for 2020 to the sudden resignation of Yang Ho Cho, the one guy in South Korea who had the 2018 Winter Games ship — finally — moving in the right direction.

IOC leadership has a bully pulpit. But no. It has been notably quiet when it could and should be aggressive in pursuit of resolution to all these challenges.

But that does not mean it is up to the United States to decide unilaterally that it is an American burden, taken on willingly, to address or fix even one of these problems.

The notion of American exceptionalism — that we are different because we are us — plays well domestically.

Internationally, not so much. Indeed, in the Olympic scene, you hear time and again that the rest of the world wants way, way less American exceptionalism. To that point, senior U.S. Olympic Committee leadership has spent the past six years preaching humility, asserting that the U.S. is just one of more than 200 nations in a global movement.

Apparently that message didn’t reach Brooklyn.

In retrospect, maybe it all makes so much more sense now, the failure of that New York bid for the Summer 2012 Games. All this dropping dead.

An American civics refresher: there are 94 U.S. attorney’s offices, one for each federal district. Federal prosecutors make for one of the most powerful arms of the entire United States government.

In Brooklyn, they implausibly decided the course of action ought to be more American exceptionalism.

Like, way more. Take that, everyone. Enjoy our investigation along with your freedom fries and newly relabeled “America” beer (née Budweiser).

A little more American civics background: the planning and execution of an American bid for a mega-event such as the Games or the World Cup involves different entities that are all part of the same branch of government, the executive: the FBI and DOJ, State, Treasury and more.

The head of the executive branch is the president himself.

President Obama has been, in many regards, an extraordinary executive. If the time in which we live is not always kind to Mr. Obama, history likely will be. At the same time, he might be the worst sports president since 1776. Ever since the day in October 2009 that Chicago got the boot for the 2016 Summer Games, won by Rio, the Obama Administration’s connection with international sports has been rich with one conflict after another.

And particularly with Russia.

It was just two-plus years ago, for instance, that the president opted in advance of the Sochi Games to make a political statement regarding Russia’s anti-gay laws by naming a U.S. delegation that was to be headed by the tennis star Billie Jean King and two other openly gay athletes. (King ultimately made it to the closing ceremony; she was unable to attend the opening ceremony because of her mother’s death.)

In nearly three years as IOC president, Bach has met with more than 100 heads of state. Obama? No, and not even last October, when a good chunk of the Olympic movement’s senior leadership descended on Washington, D.C., for the meeting of the Assn. of National Olympic Committees.

At that ANOC meeting, not one ranking Obama Administration official showed up — until the fourth day. Then came a surprise appearance from Vice President Joe Biden, the protocol equivalent of a drive-by.

During his brief stay on stage, all of seven minutes, the vice president called the Olympics the “single unifying principle in the world.”

Pretty hard to mesh that with an investigation out of Brooklyn into Russian dopers.

Indeed, there’s so much wrong with the idea that American federal prosecutors are investigating the possibility of laying criminal charges in this kind of matter that it is difficult to even know where to begin.

But here we go:

— There’s no law on point.

— On what theory does the United States claim virtually unlimited, worldwide jurisdiction?

It is incredibly unclear what nexus the United States might assert here to find jurisdiction. The banking system, as in the FIFA matter? That has always been tenuous.

— Let’s play hypothetical for just a moment. Assume the case yields indictments. How in the world are you going to get defendants into the United States, particularly if they’re in Russia? Get serious.

— The Times reported that the whistleblower in another story it broke a few days ago, about alleged misconduct at the Sochi 2014 lab, the director Dr. Grigory Rodchenkov, is “among the people under scrutiny by the United States government.”

Let’s see: we want to encourage whistle-blowers to step up and report what they know. Rodchenkov, fleeing to the United States, does just that — only to become a focus of potential criminal inquiry by the feds?

It’s not hard to imagine this hypothetical: Rodchenkov applies for asylum. Such an application hinges on his “cooperation” with the DOJ, the feds in Brooklyn perhaps eager to squeeze him to be a key witness against others.

Rodchenkov already has a lawyer, the Times reported. And he said, “I have no choice. I am between two flames,” meaning the United States and Russian governments.

Also, this: Rodchenkov is living in Los Angeles. That is a long way from Brooklyn.

— Every case brought by federal prosecutors operates on two tracks: it plays out in court and, as well, in the court of public opinion. The resource of the FBI, DOJ and each U.S. Attorney is indeed significant but even that resource is finite. That means each and every prosecution has to be brought to prove a point. In essence, every single prosecution is distinguished, at some level, by notions of politics. This may not be the most popular point of view but it is indisputably true.

The Brooklyn office is the same office that is central to the FIFA case. That matter is a reach, jurisdictionally and otherwise.

This? Way more so.

And yet this is what law enforcement chooses to investigate? When surely the Eastern District of New York has more pressing issues? Like, say, shootings? Racially tinged housing issues? Antitrust matters? The list could go on and on.

— Why do U.S. taxpayers care for even a second if Russians are doping? What taxpayer interest might prosecutors be serving or protecting by going after sports dopers? None. Obviously. Otherwise Congress would have enacted a law saying something about the matter. That’s the way the American system works.

— Further:

Let’s say an American finished one position lower in x number of sports at the Games because of proven Russian doping. Would the outcome of a criminal case result in y number more medals for the United States? Or Italy? France? Mongolia? Wherever?

Take as just one of but many such examples the Olympic women’s 20-kilometer walk.

Olga Kaniskina of Russia won the event in Beijing in 2008 and crossed the line second in London in 2012. In March of this year, the Swiss-based Court of Arbitration for Sport ruled Kaniskina ineligible from August 2009 until October 2012 because of anomalies in what’s called her “biological passport,” a reading of blood markers. Thus at issue: the London silver. Third place? Qieyang Shenjie of China. Fourth? Liu Hong, China. The top American finisher? Maria Michta, 29th.

The women’s 3k steeplechase from London? The first-place finisher, Yulia Zaripova of Russia, is expected to be DQ’d for doping. Second? Habib Ghribi of Tunisia. Third? Sofia Assefa, Ethiopia. Fourth? Micah Chemos Cheywa of Kenya. The top American? Emma Coburn, ninth.

London women’s discus: Russian silver medalist Darya Pishchalnikova tests positive for a steroid. Third place? Li Yanfeng of China. Fourth? Yarelys Barrios of Cuba. The best American? Stephanie Brown Trafton, the 2008 gold medalist, in eighth.

And so on.

— Is it the DOJ’s responsibility to protect Americans from watching bad sports? Hardly.

Joke: if so, maybe it should focus on the MLS.

— The DOJ has a proven record of achieving very little, if anything, after spending considerable taxpayer dollars when it comes to high-profile sports-related corruption or doping-related prosecutions.

The two figures at the center of Salt Lake City’s tainted bid for the 2002 Winter Games, Tom Welch and Dave Johnson? The case — 15 counts against each — was dropped, a federal judge saying it offended his “sense of justice,” adding, “Enough is enough.”

Roger Clemens? Acquitted of charges he obstructed and lied to Congress in denying he used performance-enhancing drugs.

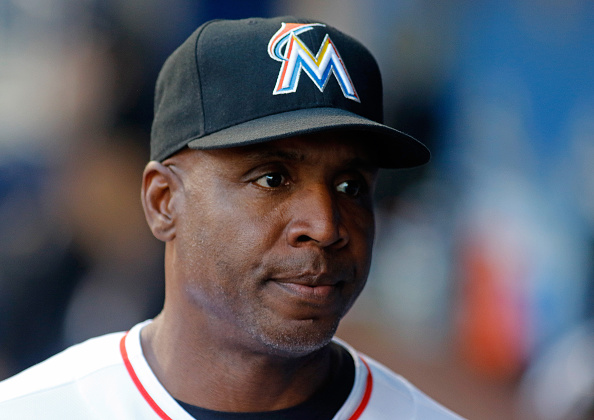

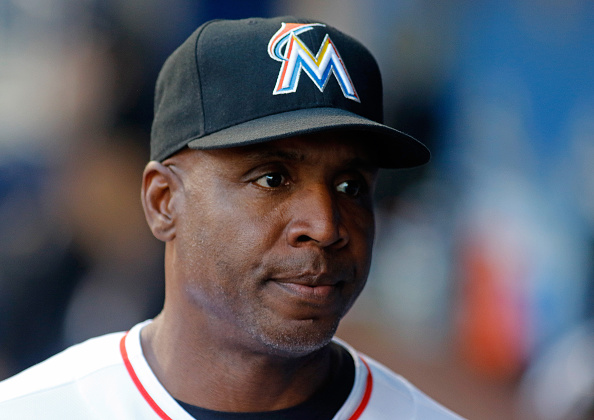

Barry Bonds? Free as a big-headed bird after nearly 10 years of facing prosecution.

Then there’s the peculiar matter involving Lance Armstrong. The U.S. Attorney’s office in Los Angeles spent nearly two years investigating allegations that Armstrong and his cycling teammates committed a variety of potential crimes via doping. A grand jury had even been convened. Then, in February 2012, the case mysteriously just — stopped. Over and done. No more.

For years, Armstrong denied doping. He said at the time the criminal case was dropped that he was “gratified,” adding, “It is the right decision and I commend them for reaching it.”

So strange, still. Eight months later, the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency released more than 1,000 pages of evidence against Armstrong. Three months after that, there was Armstrong with Oprah Winfrey, purportedly confessing all.

The addendum: the chief prosecutor of the LA office at the time, then-U.S. Attorney André Birotte Jr., was confirmed in July 2014 as a federal judge. That's a lifetime job.

For those keeping score: the former chief prosecutor in the Brooklyn office, Loretta Lynch, is now attorney general of the United States.

Remember: politics attends virtually everything involving the U.S. attorney’s office, wherever, wherever and however.

— Finally, when did it become a key DOJ agenda item to make U.S. foreign policy?

The idea that federal prosecutors could be so narrow-minded as to not take into account the LA24 bid, or American soccer ambitions for 2026, seems like a classic case of one executive branch hand (prosecutors) not knowing what the waggling fingers on the other hand might be up to.

Or, more probably, not caring.

Simply put: this is likely to pose a huge challenge for the USOC, the LA24 committee and others in the sports movement.

The FIFA thing was already difficult enough to try to explain amid the complicated matrix that underpins any U.S. sports bid.

Beyond which, any number of IOC members are known post-9/11 to be wary of travel to the United States. No one from another country likes being treated like a potential terrorist upon arrival. Especially IOC members.

Any number of members are also cautious, if not more, when it comes to what they perceive as a Wild West-type American gun culture. Among their questions: is it really safe to go to a college campus when there are open-carry laws? What about an Olympics with so many people carrying so many guns?

Now this from Brooklyn, and what is sure to be the follow-on assertion by any number of members that they must fret about every credit-card receipt if any financial transaction credibly can provide a tie to the U.S. legal system.

If the easy answer to that is, hey, IOC members, don’t do anything wrong — sure.

The simple rejoinder: it’s the cities that have proven the much-larger problem in IOC bidding, not the members per se.

At any rate, that doesn’t answer the salient question, which is: in September, 2017, with Paris, Rome and Budapest in the field along with Los Angeles, which city is going to get a majority of IOC votes?

As a policy matter, securing an Olympic Games is a way better proposition than going after some Russians. Politically, economically, culturally and in virtually every other way: winning a Games is a better bet.

At one point, you know, even President Obama thought so. He put his prestige on the line for Chicago, his hometown. Nothing has been quite the same since.