There are many versions of the story of the starfish on the beach. This is the one that over the past 15 or so years has guided the remarkable work of the International Table Tennis Federation as it has grown to become a powerful force for one-on-one change and, as well, a vehicle for the notion that sport can help promote peace in even the farthest reaches of our world:

A storm washes up thousands upon thousands of starfish on the sand. An older man walking along the shore notices a boy who seems to be dancing. The gentleman comes close and sees the boy is not dancing but throwing starfish, one by one, back into the sea.

“Why are you doing that?” the older man asks. “You can’t save them all. You can’t possibly make a difference!”

At that, the boy bends down and throws a starfish into the water. And then another. And yet another.

He says: “Saved that one. And that one. And that one.”

Earlier this month, at its annual general meeting, which this year was held in Tokyo, the ITTF brought both Mali, in Africa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands on board as national associations. Those two lifted the total of member federations on the ITTF roster to 220, tying the international volleyball federation, FIVB, for most in the world.

Afghanistan, for instance, became a member in 2005; Papua New Guinea in 2009; Chad in 2012.

Just for comparison: track and field’s global federation, the IAAF, has 212 member federations.

Only five outliers have a national Olympic committee — for context, again, there are 204 formally recognized NOCs — but are not yet recognized as an ITTF national association. Four are African: Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, Sao Tome & Principe and Eritrea. The fifth: Bahamas.

The ITTF goal is to have all five in the fold by the Rio 2016 Summer Olympics.

To show you the reach of table tennis:

The Pacific island nation of Vanuatu sent five athletes to the 2012 London Games. Two of the five played table tennis.

Until 2012, the Middle Eastern state of Qatar had never before sent women to the Summer Games. It sent four women to London. One was a 17-year-old table tennis player, Aia Mohamed.

The ITTF story is all the more notable because table tennis — in the aftermath of 1970s ping-pong diplomacy — became an Olympic sport only in 1988, at the Seoul Summer Games.

It wasn’t until 1999 that the ITTF’s formal development program got underway. By then, the ITTF had 180 members. The program was launched with $60,000 — $30,000 from the federation itself and $30,000 from the Oceania confederation of Olympic committees.

Now it has grown, all in, to nearly $2 million annually.

At the beginning, the program had a “staff” of one.

Now it has a full-time staff of 10, part-time of 100, serving over 100 nations -- all of it part of the ultimate goal, according to ITTF chief executive Judit Farago, of table tennis being recognized as a top-five sport in the Olympic movement.

To be obvious:

Soccer is the easiest game to organize, because all you need, really, is a ball. Then come basketball and volleyball, because you need a ball and a net. Then table tennis, because you need the rackets, a ball, a net (or a board or even boxes); and then anything, literally almost anything, can serve as the table, including a door, a table (to be even more obvious), a sheet of marine plywood (widely available throughout the world), school desks pushed together, whatever.

In comparison to the other sports, however, table tennis has an incredibly enviable upside. It doesn’t take up much room. It can be played indoors or out. And it doesn’t take a dedicated space; the “table” can be packed or folded up and put away. Thus it is, practically speaking, a complete winner.

Too often, the administration of sport is derided as (mostly) men in suits. In this instance, some forward-thinking suits recognized the elegance inherent in table tennis. Over the years, they have included:

Monaco-based Peace and Sport, directed by Joel Bouzou; the German table tennis federation, and in particular its president, Thomas Weikhart, and secretary general, Matthias Vatheuer; Butterfly, the Japanese table tennis company founded by Hikosuke Tamasu, who as a young soldier in 1945 was but two kilometers away when the atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima; and the Foundation for Global Sports Development.

So, too, the United Nations Office on Sport for Development and Peace, headed by its special adviser, Wilfried Lemke.

In particular, the ITTF project has been guided by the vision of Adham Sharara, its president since 1999, and his “P4” philosophy for the federation— popularity, participation, profit, planning — now expanded in recent years to a fifth p, promotion.

Mostly, however, the project has been implemented from the start — and is even now overseen — by Glenn Tepper, an Australian, a former school teacher, national team player and coach whose passport has many, many pages. He’s at nearly 100 countries, most of them developing nations.

It might sound romantic beyond imagination to be doing a table tennis course in Bora Bora, in French Polynesia. This was not, however, a honeymoon. Tepper slept in a hammock on a balcony. The mosquitoes were ferocious.

In the early years, there was a lot sleeping in hammocks. Or open-walled huts. Or cement floors. He rode a lot of local buses. He hitchhiked. He walked, a lot.

Tepper was that staff of one, and that $60,000 had to go a long way.

The payoff was in breaking down barriers. In providing something not just different but potentially better — to help even one kid see that a bigger world was out there. In maybe offering a glimmer of hope.

Kiribati is a collection of 33 islands in the central tropical Pacific. Its permanent population is now about 103,000. It was one of the first places Tepper went on this mission. He was struck while there how many people lived in thatched huts — no walls — on platforms raised above the sea and how many had their entire worldly belongings in a single box in one corner of the hut. Most people he encountered lived on a subsistence diet of tuna and tarot. They also thought — and maybe they were right, he said — that they were rich beyond words.

While in Kiribati, a picture was taken of Tepper running a clinic; in the foreground is a 4-year-old boy. About a dozen years later, that boy, Karirake Tetabo, would go on to represent Team Oceania at the ITTF Global Cadet Challenge.

In a story two years ago Tetabo is quoted as saying, “My aim is to become firstly Pacific Games champion and later become one of the best in Oceania and, who knows, maybe the world?”

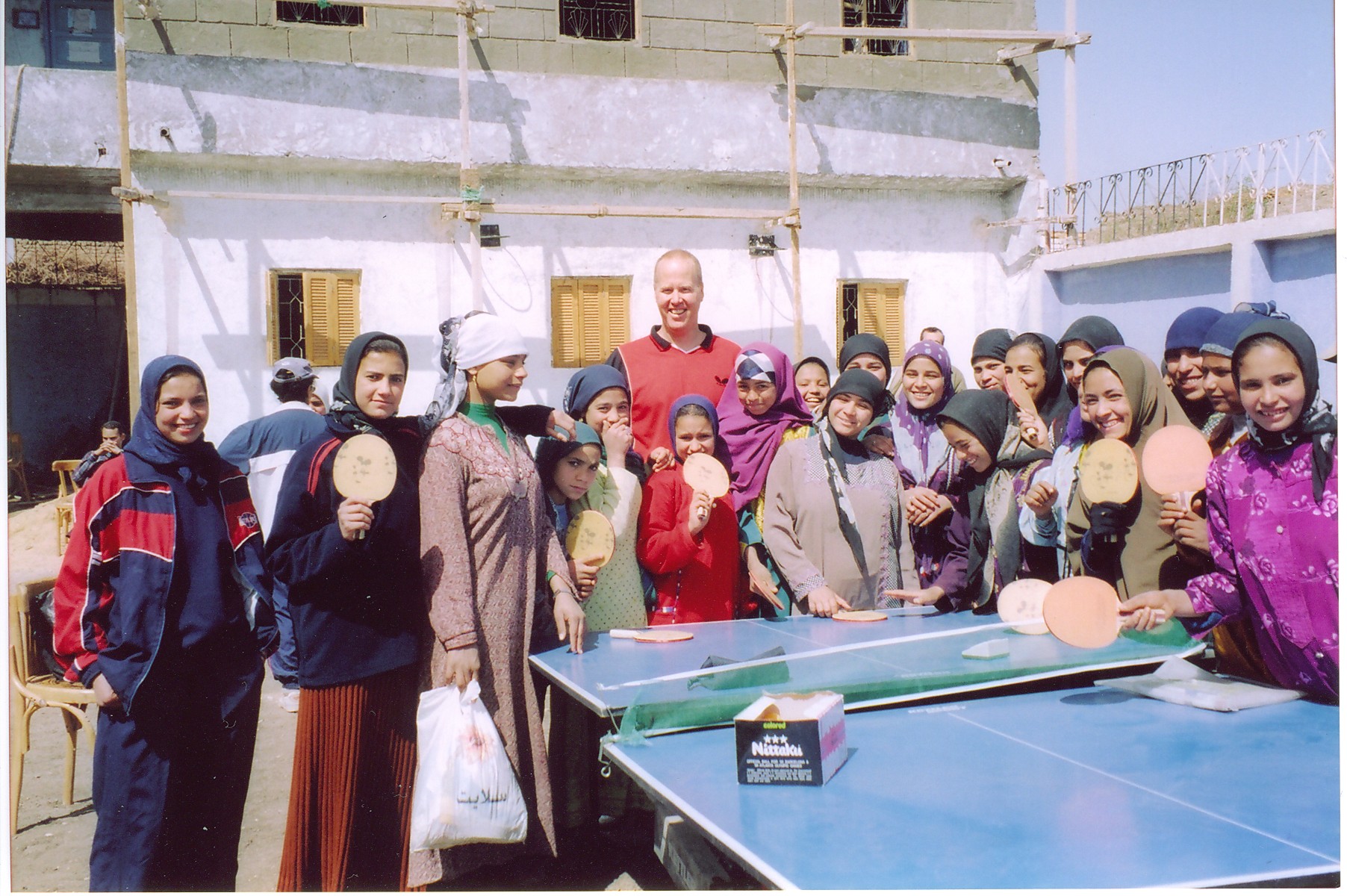

One of the first collaborative projects, it turned out, would be in 2003 in rural Egypt, Tepper and others working with village leaders in a bid to change perceptions of girls who according to tradition were being married off in their early teens and believed at risk for ritual circumcision.

One such leader, in a short ITTF video, calls the project an “excellent initiative” and gives thanks to God, saying it “increased activities” in the village community center, “especially for young women.”

Over the last Olympic cycle, 2009-12, ITTF organized 492 courses; 98 were done in accord with the International Olympic Committee’s Solidarity initiative; around the world, these 492 courses reached 24,000 people, 38 percent of whom — up from 33 percent in the previous four-year cycle — were women.

Of those 492, 206 — or 42 percent — included education about Para Table Tennis. That was up from 14 percent in the 2004-08 cycle.

In 2009, a notable ITTF initiative included “Ping Pong Paz.” It focused on children from displaced families living in slums in three cities in Colombia — 600 kids.

In 2010, it was halfway across the world, in Dili, East Timor, for “Ping Pong Ba Dame,” with the Swedish champion Peter Karlsson, a relentless promoter of table tennis as an agent for good.

In Dili, Jose de Jesus, president of the local Action for Change Foundation, after recounting the civil war there four years before, asserted that the program would promote “tolerance, discipline, morals and respect for each other.”

In 2011, the ITTF launched one of its most ambitious projects, “Ping Pong Paix,” reaching across borders in central Africa, two villages in Burundi, two across the line in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The area had been marked for some time by conflict and, indeed, outright skirmishing.

Again, Karlsson was on hand.

“The kids,” Tepper said, “found out they were exactly the same. They weren’t so different. They could have fun and become friends.”

Ultimately, the ITTF would take kids from each village to the 2012 world championships in Germany. Needless to say, these kids had not been on airplanes before. They didn’t have passports. Some didn’t even have shoes. It all got figured out.

At those championships, the kids watched the action, mingled with the sport’s stars, got all wide-eyed. They also presented Sharara with pictures they had drawn from their villages. Tepper said, “There were a lot of people with tears in their eyes who are normally tough customers.”

There’s a video that, in part, features one of the kids at those championships.

Billy Quentin Nkingi, then 12 years old, looks into the camera and, speaking in French, says, “Hello, I am Billy. I am from Burundi. I am happy to be here. This is the first time I have been to such an occasion. I am here for peace.”