NASSAU, Bahamas — The crowd was loud for the local boys’ 4x400 race. That was with Thomas A. Robinson Stadium not even maybe one-quarter full. With 19 people in line downstairs for the Kings of Jerk chicken ($10) and pork ($12), it would be more than an hour until the pros took to the blue Mondo track, two more after after that until the Bahamas Golden Knights, with three of the four guys who won Olympic gold in London two years ago in the 4x4, lining it up. Then the place all but erupted.

It’s a no-brainer why the IAAF is coming back here next year for the follow-up edition of the World Relays.

Next year’s meet will be held earlier, the first weekend in May, straight after the Penn Relays. The Youth Olympic Games this summer in Nanjing, China, will feature mixed boys and girls relays, and who knows how that will play for the 2015 event in Nassau? Maybe, too, there might be medleys or sprint hurdles. It’s clear, too, that there need to be more women’s teams in the 4x1500.

But these are all nice problems to have.

Because, frankly, every track meet should be like this.

This meet had passion.

Unlike, for instance, the first few days of last year’s world championships in Moscow, where Luzhniki Stadium was way too empty, here Robinson was alive and jamming. It was 79 years to the day that Jesse Owens had done his thing, tying or setting four world records in the space of 45 minutes at the Big Ten championships, and all of a sudden Sunday track and field was vital again.

They went crazy here, cheering loud and long for the consolation final in the men’s 400, won by the Belgians. The consolation final!

Passion is what track and field needs.

Passion is what the Bahamas delivered, along with great weather, spectacular scenery, a Junkanoo band, fantastic hospitality, first-rate facilities and a fast track that produced three world records, 37 national records and, overall, saw the U.S. team — and especially the U.S. women — dominate the meet.

One world record came Sunday night in the men’s 4x1500, courtesy of — who else — the Kenyans. Two came Saturday, in the women’s 4x1500 and in the men’s 4x200.

The Kenyan men destroyed the 4x1500 record by more than 14 seconds. The new time: 14:22.22.

Asbel Kiprop ran a 3:32.3 anchor. He pointed the baton at the finish line. After the victory ceremony, the Kenyans threw their flowers to the crowd. More roars.

The U.S., anchored by Leo Manzano, ran an American-record 14.40.80. Ethiopia — which had to battle visa issues just to get here — finished third, in 14:41.22.

As for the U.S. women:

On Saturday, the 4x100 team won in 41.88.

Then came victories Sunday in the:

— 4x400, keyed by a killer third leg from Natasha Hastings, in 3:21.73.

— 4x800, with Chanelle Price leading off and Brenda Martinez anchoring, in 8:01.58. Kenya finished second.

"It started to get loud and I just wanted to bleed for my teammates,” Martinez would say afterwards.

— 4x200, in 1:29.45, with Great Britain second, 17-hundredths back. Jamaica took third in 1:30.04, Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce anchoring.

Gold in the 100, 200, 400, 800 — and silver, after a fall, in the 1500.

There was one other U.S. victory Sunday.

Just not one the crowd came to see.

The Bahamas’ line-up in the men’s 4x400 featured Demetrius Pinder, Michael Mathieu and Chris Brown, just like two years ago in London. LaToy Williams subbed for Ramon Miller. Williams opened it up; Pinder ran second, as usual; Brown, third (he had run first in London); Mathieu would close it out.

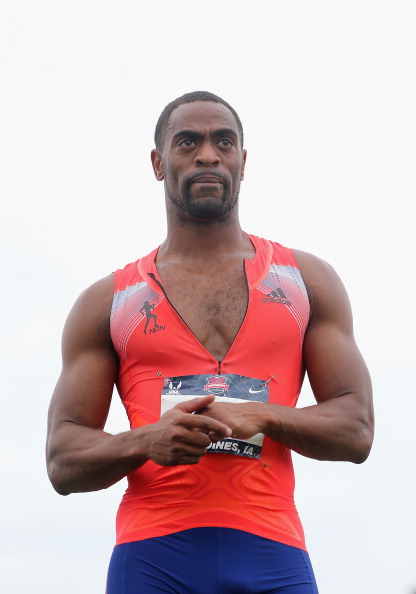

The U.S. countered with David Verburg; Tony McQuay; 2012 Olympic triple jump champion Christian Taylor, who also runs a mean 400; and LaShawn Merritt, who is the 2008 Olympic as well as 2009 and 2013 world champion in the 400.

Merritt is also a gold medalist at the 2007, 2009, 2011 and 2013 4x400 relays.

It takes nothing — repeat, nothing — away from the Bahamas gold in 2012 to note that LaShawn Merritt was hurt and did not run in London.

The Bahamas defeated the U.S. in April at the Penn Relays; the U.S. has never lost to the same team twice in a row in the men’s 4x4.

By the time Brown handed off to Mathieu, the Bahamas had a four-meter lead. The music was at full roar. The place was jumping. It was loud. It was exciting. It was great theater.

The men’s 4x4 was, simply put, an advertisement for track and field.

Merritt is 27, 28 at the end of June. He has been through it and come out the other side. Not just on the track but, as has been well-documented, off. He has matured and is as mentally tough a customer in not just this sport but any sport.

He tried a move at 250 meters. Nothing there. So he settled in and waited, behind Mathieu, for the turn.

And then just turned it on.

Down the stretch, LaShawn Merritt showed why he is one of the great 400 runners in history.

He didn’t just run Mathieu down, he buried him.

The clock read 2:57.25 when Merritt crossed first, the crowd suddenly very, very quiet.

Mathieu crossed next, in 2:57.59. Trinidad & Tobago took third, in 2:58.34.

Merritt’s final split: 43.8.

Mathieu’s: 44.6.

“Of course we felt some pressure,” Merritt said later. “It was a big business for us. The Bahamian guys sometimes do trash-talking so we wanted to come out here and, in front of their fans, prove that we’re the best in the world.”

The U.S. men didn’t get the chance to challenge almighty Jamaica in the men’s 4x1. Anchored by Yohan Blake, the Jamaicans won in 37.77. The Americans didn’t run in the final. They had been disqualified in the heats — the result of yet another bad pass, this time Trell Kimmons to Rakieem Salaam, Man 2 to Man 3 on the backstretch.

By the time the pass got completed, the guys were way out of the zone. Obvious DQ.

The men’s 4x2 team had been DQ’d Saturday for another out-of-zone pass.

It surely will prove little consolation that the Jamaican 4x4 team Sunday dropped the baton.

Some context:

Of the last 11 major championships, world or Olympic, including these Relays, dating back to 2001, the U.S. men’s 4x1 team has been DQ’d or DNF’d five times — again, out five of 11.

It’s six of 11 if you include the retroactive doping DQ for the 2001 team.

There is only one word for that: unacceptable.

What is far more problematic is that USA Track & Field has been down this institutional road before. See, for instance, the Project 30 report from 2009.

Looking ahead now to the world championships in Beijing in 2015 and to the Rio Summer Games in 2016, and even beyond, one of the key action points going forward for USATF has to be addressing its sprint relay issues.

Some of what happened here may be, simply, that runners took off too early. That can happen.

Then again, it may also be the case that USATF would be well-advised to name a relay coach — someone in charge of just the relays — and get this right.

There is ample history for any reasonable person to argue that USATF is dysfunctional and incapable of this or that.

There’s also the counter-argument that, at some level, USATF must be doing something right. The 29 medals U.S. athletes won at the London Games didn’t just happen.

Duffy Mahoney, USATF’s high-performance director, has been involved in track and field for decades.

He was alternately sanguine about the DQ’s and resolute about the need to get results.

“Life,” he said, “is what happens to you while you are making plans.”

He also said that the possibility of a full-on relay coach is “one of the beginnings of the solution.”

Who that might be, of course, is a mystery.

It’s hugely unlikely to be Jon Drummond. He is now enmeshed in all kinds of legal complexities involving the Tyson Gay matter. Beyond which — to think that Drummond is the only person in the United States who can coach up the relays is absurd.

Dennis Mitchell served here. On the one hand, the women won, and for the most part they were not the Olympic A-listers. But, again, the men had issues. And Mitchell has a significant PR issue because of his doping ties.

The relays involve timing, communication and confidence. And more.

As Manteo Mitchell, a courageous silver medalist at the London 2012 for the U.S. team in the 4x400 relay, posted on Twitter Sunday within minutes after the 4x100 debacle, without further comment, “Too many egos in one group.”

The Jamaicans seemingly have proven you don’t need group therapy to run the sprint relays. The Americans shouldn’t, either.

A light rain began to fall late Sunday as they wrapped it all up here, the Americans pondering what’s next, the IAAF exuberant.

“In the ‘sun, sea and sand paradise’ that the Bahamas markets itself, we have experienced a true sporting paradise which has excelled beyond our expectations,” Lamine Diack, the IAAF president, said. “The people have embraced the IAAF World Relays and the noise of their support will be left ringing in our memories for many years to come.”

As the rain fell, Timothy Munnings, the director of sports in the Bahamas’ ministry of youth, sports and culture, walked through the stands.

He stopped to talk with some journalists, asking — earnestly — how the event had gone.

“Thank you for coming,” he said. “Next year, you’ve got to be back.”