KAZAN, Russia -- This week in Tokyo, eight sports are making their pitches to be part of the 2020 Olympics. For those eight, being part of the Olympic program would mean hundreds of millions of dollars, particularly as governments around the world look to develop athletes, coaches, facilities and grass-roots participation structures. Understanding just how much interest there is in what might be added to a future Olympic sports program, the chairman of the Tokyo 2020 coordination commission, John Coates, said back in February: “The whole world is looking at this process, not just the people of Japan. Many sports are interested and this is going to be a very transparent process.”

Transparency.

That’s a buzzword that features strongly in the IOC’s would-be reform plan, dubbed Agenda 2020.

President Thomas Bach mentioned it eight times in his opening speech last week to the 128th IOC session in Kuala Lumpur. He said, in part: “People today demand more transparency and want to see concrete steps and results on how we are living up to our values and our responsibility. We need to demonstrate that we are indeed walking the walk and not just talking the talk.”

Just in case that wasn’t clear enough, the word came up again several times in remarks to the IOC members from their invited keynote speaker, Sir Martin Sorrell.

It would be naive to imagine the IOC didn’t have some advance idea of what Sir Martin was going to say: “You have to run your operation, totally, on a transparent basis because there’s no other way that you can do it… Sunlight is good.”

So in the spirit of transparency, what do we know about what’s being pitched in Tokyo?

Very little.

Sure, we know the names of the federations invited to pitch. But precious little else.

The pitches took place behind closed doors: no media in the room and certainly no online livestream. Representatives of the international federations making the pitches held up copies of their bid books for the media to see but don't try downloading them from the federation websites. They’re not there.

Lars Haue-Pedersen & @JBelmo explain @WorldBowling’s plans to the media #Tokyo2020 pic.twitter.com/SQeuy8efKS

— TOKYO ● 2020 (@Tokyo2020) August 7, 2015

Compared to the IOC’s own existing standards—for cities bidding to win the Olympics—things in Tokyo are looking, well, opaque.

Some of the sports pitching for 2020--skateboarding and surfing spring to mind--have entrenched internal opposition to being included in the Olympics. Opponents like that don’t just go away because you try to do things quietly: the lesson of Boston’s Olympic bid should be clear.

Back to last week in Kuala Lumpur. Like all great advertising execs, Sir Martin has a keen sense of what his clients want to hear. He made a lot of sense while making it plain that a multi-faceted attempt to distribute Olympic video content in a social way online is vital to maintaining relevance. Sir Martin backed up his assertions with clear and compelling data. The Olympic Games need to reinvent themselves for generations of young people who themselves have been reinvented by new technology.

Sir Martin spoke at length about YouTube, about millennials and about even younger users who consume most of their video online through mobile devices. This was exactly dead-on right. YouTube has exactly the kind of user age the IOC would love to be engaged with the Olympics:

To reach these young people, though, the Olympic product itself has to change, and not just the way that product is distributed.

This is fundamental.

There is, as ever, talk about this. But talking the talk and walking the walk are two very different things.

Here was Coates, speaking this past February: “Universality and gender equality are key in selecting new sports or events but the IOC will also consider an up-and-coming sport that is gaining in popularity especially with youth.”

Bringing in the new will, however, be genuinely very difficult.

Changes to the Olympic program marked the biggest test of Jacques Rogge’s presidency, which ran from 2001 to 2013.

The absence of transparency over additions to Tokyo 2020 suggests changes to the Olympic program are already becoming the biggest test of Bach’s presidency, too.

The Tokyo 2020 battle, meanwhile, will be nothing in light of the real fight to come — when the Olympic sports incumbents fight to stay on the program for 2024, to keep every last part of their medal and athlete quotas.

A taste of what’s in store: existing sports have proposed some novelties for the Buenos Aires 2018 Youth Olympics. But there are no new sports on the program.

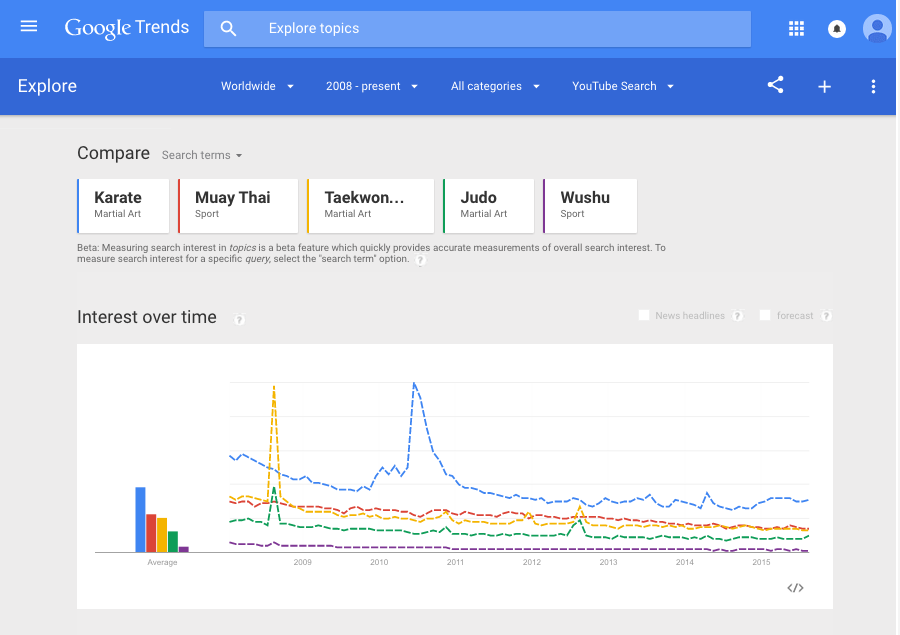

At the same time, it is not particularly difficult to see what is up-and-coming, gaining popularity with young people. Google will tell you what works for the YouTube demographic just by typing in the search terms. Consider the options for martial arts:

Even with the benefit of incumbency on the Olympic program, taekwondo and judo just aren’t as interesting to YouTubers as karate and muay Thai. So it makes sense, of course, that karate would be on the short list for Tokyo 2020. But where is muay Thai? It isn’t even "recognized." as the term of art goes, by the IOC. And only recognized sports (including tug-of-war and polo) were invited to apply. Wushu, however, is also recognized. So it made the shortlist, too. For the record, arm wrestling is bigger on YouTube than wushu.

The social media platforms and behaviors that Sir Martin Sorrell detailed for the IOC are responsible for popularizing new sports at previously unimaginable speeds. The heavy hitters of this new generation of sports, like parkour and obstacle-course racing, were barely known 10 or even five years ago. There are others, too.

Take calisthenics and street workout. It’s already bigger on YouTube than equestrian. The sport’s biggest star, Frank Medrano, has a third as many Facebook fans as the entire Olympics and twice as many as the world’s best-known surfer, Kelly Slater.

Finding out what the youth of the world wants to engage with is easier than ever. But the challenge confronting the IOC is twofold: 1. Can it can keep up with the ever-increasing pace of change? 2. Does it have the will to do so?

It is clearly possible — under a strong leader — to bring new things into the Olympic movement. Medals were being handed out for modern pentathlon five years after the French baron Pierre de Coubertin dreamed the sport up. Under Juan Antonio Samaranch, the IOC president from 1980-2001, triathlon’s governing body was established and recognized, the sport then given full medal status, all within a few years. No one can possibly doubt that triathlon has become a fine addition to the Olympic program.

So where are the new Agenda 2020-era additions to the Olympic movement? The World Flying Disc Federation and its main sport, Ultimate Frisbee, were recognized last week in Kuala Lumpur. That’s a 50-year-old sport with the same level of YouTube interest as wushu.

Youth engagement, flexibility and transparency are admirable goals. But if Agenda 2020 is to work, to be more than just talk, then those ambitions needs to drive processes and events, not the other way around.

It’s time to walk the walk, bring in the new and tell the whole world about it.