It’s Oscar Sunday here in Los Angeles. “La La Land” is expected to clean up.

Ladies and gentlemen and boys and girls, let’s turn the lights down low, settle back into our comfy seats with a big tub of popcorn and, what with the weekend's super-interesting script ripped from the Sunday Times over in London tied to a Fancy Bears hack all about Alberto Salazar and Sir Mo Farah and others, let’s revisit some showstoppers from years gone by.

What an interesting idea, just generally speaking: when the presumption of innocence meets la-la land.

But first:

Just like at the movie theater, when they tell you to turn off your cellphone, this disclaimer, brought to you Saturday from the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency:

“Importantly, all athletes, coaches and others under the jurisdiction of the World Anti-Doping Code are innocent and presumed to have complied with the rules unless and until the established anti-doping process declares otherwise. It is grossly unfair and reckless to state, infer or imply differently.”

https://twitter.com/Ry_Madden/status/835659821059735553

Oh, wait.

For clarity: do these rules apply with the same import to Russian athletes?

Because this would be the same U.S. Anti-Doping Agency that over the past 18 months has helped promote the charge to ban each and every Russian athlete because of allegations involving what an independent World Anti-Doping Agency-commissioned report alleged was “institutional control” of the Russian anti-doping control system.

Just to reiterate from the USADA press aide's tweet, italics and underline mine: "all athletes, coaches and others … are innocent and presumed to have complied with the rules unless and until the established anti-doping process declares otherwise.”

For emphasis:

“It is grossly unfair and reckless to state, infer or imply differently.”

A U.S. Congressional subcommittee meets Tuesday to consider “ways to improve and strengthen the anti-doping system.” Perhaps this can be on the agenda.

La, la, la, la, la.

Returning, as we were, to a story seemingly crying out for a Hollywood-style treatment:

The Sunday Times, citing a Fancy Bears hack of a March 2016 USADA report, says Farah and others were given infusions of a research supplement based on the amino acid L-carnitine.

The newspaper says Salazar boasted about the “incredible performance boosting effects” of the stuff and emailed Lance Armstrong before Armstrong was outed for doping: “Lance call me asap! We have tested it and it’s amazing.”

Farah, in a Sunday post to his Facebook feed, said it was “deeply frustrating” to have to respond to such allegations and asserted he was a “clean athlete.”

To reiterate, Farah is, and the others in the Salazar camp are, assuredly entitled to the presumption of innocence.

Scriptwriters out there: do you know what might, just might, make for a really interesting take on the Farah saga? In retrospect, if you will, maybe the turning point in the whole thing?

In 2011, at the IAAF world championships in Daegu, South Korea, Farah lost the 10,000 meters by just this much, to a guy perhaps only true track geeks have ever heard of, Ibrahim Jeilan of Ethiopia.

After some 26 minutes of racing, Farah ran the last lap in 53.36 seconds, which is crazy fast.

It wasn't enough.

Jeilan won, in 27:13.81.

Farah got the silver, in 27.14.07.

Since, Farah has pretty much won everything of import, including both the 5 and 10k races at London 2012 and Rio 2016.

Jeilan isn't exactly a total chump. He was the 2006 world junior 10k champion. He is the 2013 10k world silver medalist.

But since that fateful evening in Daegu, Aug. 28, 2011, their career paths have — diverged.

One might ask: how come?

Moving along, as we were.

In 1978, when I was a second-year student at the Northwestern University Medill School of Journalism in Evanston, Illinois, the best-picture winner was “Annie Hall.” Talk about neurotic. You want neurotic? Here was neurotic: a second-year news writing class, taught by a crusty curmudgeon straight from central casting, Dick Hainey, in which we were taught that one mistake, even one, would get you an automatic failing grade and, son, you deserved to fail and, better yet, start learning to suck it up, because anything less than perfect obviously equals abject failure.

Here is another decree from the oracle atop the mountain that was Professor Hainey, and while anything less than perfect turns out maybe to be not such great advice for life, this next nugget is a worthwhile journalism lesson that has stuck for more than 40 years:

If your mother tells you she loves you — check it out.

In that spirit— and, once more for emphasis, Sir Mo and the others in the Salazar pack are assuredly entitled to the presumption of innocence — let us visit some hits from the wayback machine even as we note that Julia Roberts is, according to Variety, set to produce the film adaptation of the New York Times best-seller “Fool Me Once”:

Armstrong, 1999: “I have been on my deathbed, and I’m not stupid. I can emphatically say I’m not on drugs.”

Armstrong, 2005: “I have never doped. I can say it again but I’ve said it for seven years.”

Armstrong, 2005: “How many times do I have to say it? … Well, it can’t be any clearer than, ‘I’ve never taken drugs.’ “

Armstrong, 2010: “As long as I live, I will deny it. There was absolutely no way I forced people, encouraged people, told people, helped people, facilitated. Absolutely not. 100 percent.”

Armstrong on Twitter, May 2011, as his former teammate Tyler Hamilton was about to go on “60 Minutes”:

https://twitter.com/lancearmstrong/status/71358750434402306

Armstrong, 2013, after USADA got him: “All the fault and all the blame here falls on me. I viewed this situation as one big lie that I repeated a lot of times. I made my decisions. They are my mistakes, and I am sitting here today to acknowledge that and to say I’m sorry for that.”

Hamilton, interview in his Boulder, Colorado, living room, 2005: “I didn’t blood dope, that’s for sure.”

Hamilton, May, 19, 2011, confession letter to family and friends: “During my cycling career, I knowingly broke the rules. I used performance-enhancing drugs. I lied about it, over and over. Worst of all, I hurt people I care about. And while there are reasons for what I did — reasons I hope you’ll understand better after watching — it doesn’t excuse the fact that I did it all, and there’s no way on earth to undo it.”

Hamilton, describing a July 2000 blood transfusion during that year’s Tour de France, as relayed as part of the USADA case against Armstrong:

“The whole process took less than 30 minutes. Kevin Livingston and I received our transfusions in one room and Lance got his in an adjacent room with an adjoining door. During the transfusion Lance was visible from our room, Johan, Pepe and Dr. del Moral were all present and Dr. del Moral went back and forth between the rooms checking on the progress of the re-infusions. Each blood bag was placed on a hook for a picture frame or taped to the wall and we lay on the bed and shivered while the chilly blood re-entered our bodies.”

Floyd Landis, his very own 2007 autobiography, the ironically titled Positively False, chapter 11:

“I did not use performance enhancing drugs in the 2006 Tour de France or any other time in my career. All I ever did was train. I put training first, even before my family. When you want to win, you eat, drink, sleep and breathe cycling. Knowing it’s not forever is what makes it doable. So I made the sacrifices I had to make, and I did so honestly.”

From page 278-79 in the book, Landis describing a post-2006 Tour de France trip back to where he was from, Farmersville, Pennsylvania, amid the largely Mennonite area of Lancaster County:

"One by one, hundreds of people walked across the yard to my parents to congratulate them. One woman went to mother with tears in her eyes. 'She said that she and her husband had lost their son in Iraq seven months before,' Mom said. 'She told me, 'My husband has never gotten over it, but he rides a bicycle and he watched every single stage. He's a different person since your son won. It was like healing to him.' I just felt so blessed that you were able to inspire someone while doing something that you love,' Mom told me. I never rode my bike in order to have an effect on anyone else, but I understand that people are influenced by what they see. When my mom told me this story, I was really touched that I had helped someone."

USADA Reasoned Decision, just one of many harrowing passages describing Landis' doping: “They shared doping advice from Michele Ferrari," the Italian doctor identified by USADA as a key player in the Armstrong scheme, "and when Floyd needed EPO Lance shared that, too.”

Marion Jones, her very own 2004 autobiography, and in big red capital letters about 175 pages in:

“I have always been unequivocal in my opinion. I am against performance-enhancing drugs. I have never taken them and I will never take them.”

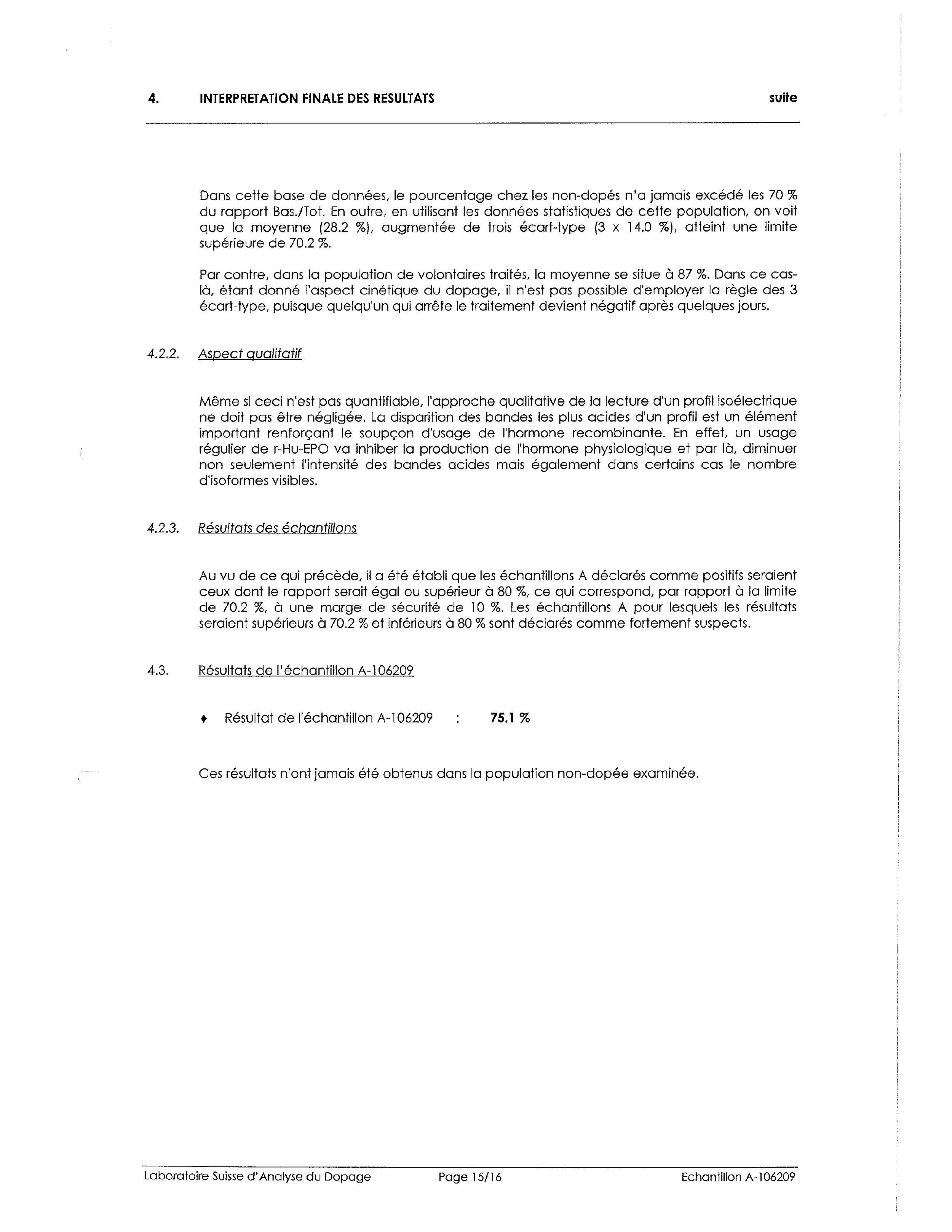

Government sentencing memorandum, 2007, United States v. Marion Jones:

“The defendant’s use of performance-enhancing drugs encompassed numerous drugs (THG, EPO, human growth hormone) and delivery systems (sublingual drops, subcutaneous injections) over a substantial course of time. Her use of these substances was goal-oriented, that is, it was designed to further her athletic accomplishments and financial career. Her false statements to the [investigating] agent were focused, hoping not only to deflect the attention of the investigation away from herself, but also to secure the gains achieved by her use of the performance-enhancing substances in the first place. The false statements to the [investigating] agent were the culmination of a long series of public denials by the defendant, often accompanied by baseless attacks on those accusing her regarding her use of these substances."

U.S. District Judge Kenneth Karas, 2007, in sentencing Jones to six months in custody, emphasizing that what she did was not a “momentary lapse in judgment or a one-time mistake but instead a repetition of an attempt to break the law.”

Who knows what will happen at the Oscars?

What the next few weeks or months will bring with Sir Mo, Salazar and others?

Surprises and plot twists galore, perhaps.

La, la, la, la, la, everyone. Keep a watchful eye on your sweet mother and the popcorn.