What’s nine times nine, everyone? When you get poll numbers that scream 81 percent in favor of the Olympic Games coming to your town, the result of an early August poll in Los Angeles conducted for the U.S. Olympic Committee, that’s when you know, with certainty, that an LA 2024 bid would be good for Southern California, the USOC, the International Olympic Committee and, indeed, the broader Olympic movement.

81 percent!

That is crazy high in a democracy. You can’t even get that number of people who want Donald Trump to zip it.

As USOC chief executive Scott Blackmun said Wednesday in a telephone call with reporters, referring to that 81 percent, “That’s remarkable and very encouraging.”

Here is the other side:

Only 11 percent — 11 percent! — said, no thanks, not really feeling an LA 2024 Games.

That is crazy low.

There is sound basis for both these numbers, and it underpins the fundamental reason LA 2024 offers so much potential for all involved in and around the Olympic movement.

Paris, Budapest, Rome and Hamburg, Germany, are due to be in the 2024 race. Maybe Toronto.

That said, the IOC wants to have a reason to come back to the United States. That’s apparent after talking with members at the recent session in Kuala Lumpur, where the IOC voted to send the 2022 Winter Games to Beijing.

If that’s what the IOC wants, it needs — maybe even desperately needs — a marquee city in a functioning western democracy to take on the Games for 2024.

The IOC president, Thomas Bach, referring recently to his would-be reform plan, dubbed Agenda 2020, declared that it’s not enough to talk the talk — the IOC, he said, must walk the walk.

Right now, however, Agenda 2020 is at considerable risk.

Beijing?

Where human rights protests are going to be in the news for the next seven years?

Where the 2008 Summer Games cost at least $40 billion and the 2022 Games will go down with virtually no natural snow?

Where a new high-speed train is being built up to those snowless mountains that are now two or three hours from Beijing — but the billions of dollars in construction costs for that train are not being included in 2022 accounting, a move that makes a mockery of Agenda 2020’s call for enhanced Olympic transparency?

The IOC knows — it absolutely knows — it needs for 2024 a soulful bid that makes sense.

Enter LA.

The LA 2024 plan is for a Games with an all-in budget of $4.1 billion, $4.5 including a $400 million contingency fee.

No project is without risk.

But a Los Angeles Games is almost assured of making an operating-side surplus — that’s the preferred word in Olympic speak, not “profit” — and so the risk factor is as benign as possible.

Why so benign?

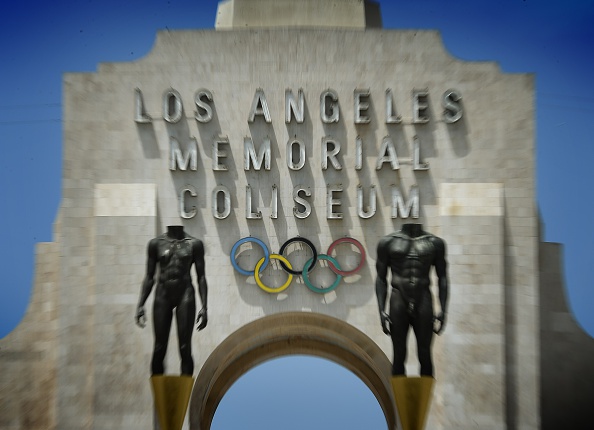

Because, just to be super-obvious, most of the venues are already built, including of course the LA Memorial Coliseum.

The prospect of an NFL team, or two, in the coming seasons means more stadium stuff on the ground — again, without taxpayer dollars.

Have cost overruns dogged any number of recent Olympics? Absolutely. Why? Because of infrastructure projects built as part of a far-reaching urban development plan linked to a Games.

In LA, that’s not the plan. No massive urban development.

It’s as much — or more — what LA can do for the Olympics as the Olympics can do for LA.

The LA City Council, the county Board of Supervisors, the governor, the Southern California congressional delegation — all unanimously in favor of LA for 2024.

Again, why?

Because in Los Angeles the Games are part of the fabric of city life.

This is a huge piece of why eight of 10 of their constituents want an Olympics, too.

“The LA Olympics would inspire the world and are right for our city,” LA Mayor Eric Garcetti said in a statement issued Wednesday.

The Games were in LA in 1932 and 1984; the mayor keeps a 1984 Olympic torch in his office. Tenth Street has long been Olympic Boulevard, after the 1932 Games, the X Olympiad. Hundreds of Olympians — and would-be Olympians — call SoCal home.

More, the 1984 Games ushered in a golden period in LA — seven really great years, in which it seemed everything in and around Southern California was awesome. The golden glow lasted until the Los Angeles police department had its altercation with Rodney King — after which followed riots, wildfires, mudslides, the 1994 Northridge earthquake, the Menendez brothers and then, of course, OJ.

People want those golden years back. And they understand that LA and the Olympics are made for each other — LA is, truly, America’s Olympic city.

In 1932, LA gave the movement the Olympic village.

The 1984 Games all but saved the movement, ushering in a period of finance and prosperity that continues now.

A 2024 LA Games would also offer the movement precisely what it needs at the exact moment it needs it — an Olympics of sustainability and real legacy in a western democracy where the Games are not just welcomed but, genuinely, celebrated.

“On the Summer side,” Blackmun said, “there’s a whole generation of Americans who haven’t seen the Games on American soil,” since Atlanta in 1996. “We want to address that, and make sure the Games come to the U.S. on a regular basis.”

If it’s a little late for the USOC to have come to its senses — better late than never.

A few more details, and this ought to be a done deal, wrapped up in time for the Sept. 15 deadline to formally submit a bid to the IOC. What details? No one Wednesday was saying but it’s only logical to surmise that giving LA an option for 2028 might be up for discussion with the USOC after the debacle that was Boston, and the perception that LA 2024 and the USOC might well have to make up of starting at a distance.

Consider: when the USOC last conducted a poll in LA, the favorability ratings were in the high 70s. That was eight months ago.

Now, 81 percent, and even after the Boston horror show.

That’s how you jump forcefully back into the game.

Blackmun said the USOC and LA are “very, very optimistic we’re going to be able to get to a place that’s good for both of us.”

USOC board chair Larry Probst: “The USOC and the city of Los Angeles believe this is potentially our time and we can work within a strong partnership to make it happen.”

He also said, “We continue to believe a U.S. bid for the 2024 Games can be successful.”