LONDON — Coming into these 2017 IAAF world championships, the American Fred Kerley was the next big thing in the men’s 400.

More precisely, Fred Kerley of Texas A&M was the next big thing. He came to London having run15 individual 400s in 2017. He had won 15.

It didn’t go Kerley’s way in the 400 final. He finished seventh, a result pre-figured in the semifinal, when he just barely qualified for the final on time. This is not to beat on Kerley. Just the opposite. It’s to pay him respect. He’s 22, and -- counting the rounds and the final here -- he ran 18 400s this year, plus a bunch of relays, plus some 200s to boot.

The NCAA system is the world’s diamond polisher. It doesn’t send up just Americans every two years to the world championships or every four years the Olympics. A great deal of the entire world sends its best to the United States, and in turn the NCAA sends its best back to the world, or the Olympics.

But take a good look around at these 2017 world championships in London. This may be a last go-around for the way a lot of things that have traditionally been the case in track and field.

The sport is looking at a great number of changes. To be candid, and with sincere respect for that tradition, it needs to change.

Change has been the hallmark of IAAF president Seb Coe’s first two years in office and any reasonable observer can see that change to the way track and field does things, in particular its presentation and its calendar, have to be on the agenda, and sooner than later.

Purists may shudder. That’s OK. All change is hard. All interest groups have interests. That’s understood.

Track and field has a historic opportunity in the United States owing to the 11-year timeline between now and the 2028 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. If the sport can make a powerful move in the U.S. market, it could and should prove transformational.

It's also the case that the post-Usain Bolt era, which literally begins Sunday, after his final race Saturday (the men's 4x100 relay), offers a clean break.

The London 2017 championships are a sell-out, which traditionalists can well cite as evidence that matters are on course. They're not. Track and field simply can’t keep keeping on and expect to keep its self-identified position as the No. 1 Olympic sport, much less emerge a dynamic sport for the 21st century with appeal to young people.

Track and field has two options. It can change. Or it can have change forced upon it in crisis.

Better to choose option A.

The worrying signals are there for all track and field lovers, and this is the big one: aquatics will have more medal events at the Tokyo 2020 Games, 49, than track, 48. Swimming, along with gymnastics, is now what the International Olympic Committee calls for revenue distribution purposes a Tier A sport. Track used to occupy that category all by itself. Volleyball, which just concluded a hugely successful beach volleyball worlds in Austria, is banging on the Tier A door, and hard.

Better, again, to choose option A.

Teen girls, for instance, want to see Snapchat stories in which, say, the runners are adorned with stickers as they fly down the track.

They love the bright-pink colors of the sweatshirts that are part of the uniforms here.

But that ‘70s and ‘80s classic rock over the stadium loudspeakers? Come on, that’s when people who are literally in their 40s and 50s, ohmigod, were in school. Old. In case there is any doubt, and there should not be: old is not good.

Why are there three “semifinals”? Semifinal means two. Everyone knows that. (Trying to explain to teen girls that there are three so that athletes and officials from around the world can go back home with the pride of saying they were a world “semifinalist” when back home very few not in and of the track and field world understand it was made comparatively easier to make a semifinal because there are three, not two — this draws blank stares from a teen audience.)

And every night! For 10 nights! Too much, and too long! Like even Coachella, the music festival, runs on consecutive three-day weekends in April. Who really wants to hang out at a track meet (maybe with parents or grandparents, ugh) for 10 nights?

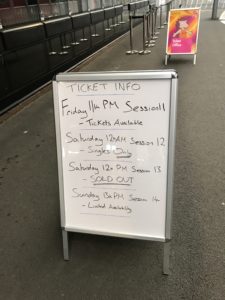

Friday’s “afternoon session” started at 5 p.m., with the high jump portion of the decathlon. It picked up again at 7:05 p.m., with (the three) semifinals in the women’s 100 hurdles. It ended just before 10, with the only final that anyone under 21 might reasonably care about, the women’s 200, because that race takes about 22 seconds and is easily Instagrammable — or, to use the lingo, good for the ‘gram.

It’s Friday night! There should be a headliner. Is that so difficult?

And why oh why are there so many events going on at the same time? It’s like going to the gym and watching people do stuff. It’s not a show! A show has a beginning, a middle and an end. It tells a story. There’s no thematic story to whatever it is that was out there. Just blips: in the race just before that 200, Emma Coburn and Courtney Frerichs of the United States went 1-2 in the women's steeplechase (why is it 3000 meters? why is water at some of the jumps?). So many rules. So many places to try to look at, all at one time. It’s super-confusing for someone new, and when the announcer has to tell you what screen to look at, that’s a problem.

A big problem — like, at an NFL game, even if you don't know the first thing about football, you know to watch the quarterback.

The central question, as ever: is track and field a made-for-TV event in which the stadium and audience serve as backdrop, or is the thing the stadium experience?

Indeed, presentation and time are at the core of many of the track world’s pressing — alternatively, most creatively intriguing and constructively provocative — challenges.

Those tensions make for a fascinating impact on athletes, coaches and more.

And they serve as an important driver as key players study what to do next.

Take Kerley and his Texas A&M coach, Pat Henry. (No tension there, to be clear.)

“I was ready to go,” Kerley said of the 400 final. “Coming home, I didn’t have that push like I normally did. I didn’t have no nerves. My body didn’t tell me to go like four or five weeks ago.”

The NCAA grind affects different people differently. Christian Coleman, a Tennessee junior, took silver in last Saturday night’s men’s 100, behind Justin Gatlin, ahead of Bolt. Trinidad & Tobago’s Jereem Richards, a junior at Alabama, grabbed third in Thursday night’s men’s 200.

And, as Henry pointed out, Kerley not only “still felt like he had something in the tank” before the 400 final,” what “got him here was running those [17 prior] 400s.” He added, “Without those, he wouldn’t have been here. It’s that time in his life. It’s that time to learn who he is, what his capabilities are. If you don’t run races, you don’t get that figured out. Many people might say it’s too many races. Sure. If the young man knew who he is and what his capabilities were — that’s track.”

As Henry also stressed, college track and field is not about getting an athlete ready for the world championships. It’s about aiming to win an NCAA championship.

“For a young man or any member of a team to be a contributor to a team sport, that’s first,” Henry said, and he’s right.

“What athletic department,” he asked rhetorically, “is going to support a track program if it’s all about the individual? That cannot be.

“I will be criticized for saying that. I am always criticized. That’s OK. We are at a point where we have to make those decisions.”

One of the factors likely to force such decisions is the next IAAF world championships, in Doha, Qatar, in 2019.

Here’s a secret: the big whisper backstage here in London — from athletes, delegates, officials and media — is all about Doha. In sum: who’s going, and why?

In an intriguing way for the IAAF, that creates opportunity.

The downside to Doha is that the meet is scheduled for September 28 to October 6, 2019. That’s obviously because of the heat.

Putting aside the heat issues, and looking at Doha from the downside of a bigger-picture calendar perspective:

Having a world championship in October in the year before an Olympic Games, when the track meet at the Games will be held the first week of August 2020, means everything will be askew in 2019. Television-wise, at least in the United States, the track and field worlds will be up against the NFL. If you like to bet, you might bet that the NFL will kill the track meet in the ratings.

Now, switching it up:

The upside to Doha is that the meet is scheduled for September 28 to October 6.

That means the IAAF, finally, can take a look at a long-overdue re-do of its calendar.

The track and field calendar has always been totally screwed up.

What sense does it make to hold your world championships and then carry on with more meets — like nothing happened?

Only track and field.

Do you see more NFL games after the Super Bowl? More basketball after the NBA Finals? More baseball after the World Series?

Yet year after year, track holds its worlds, or the Olympics, and then carries on with more Diamond League meets in Europe. What sort of business model is that?

A central question, going forward, is what is — or ought to be — the one-off? 2019? Or 2020?

To view this from a USA Track & FIeld perspective, and wrapping back to the NCAA issues:

Of the 138 athletes on the U.S. squad here in London for the 2017 championships, 23, including those who turned professional after the college championships, were NCAA-eligible. Of those 23, all were Division I with the exception of one, Chris Belcher, the 100-meter sprinter from North Carolina A&T.

Hypothetically speaking: even if those 23 were to take part in whenever (and wherever) the U.S. selection meet was to be held in 2019, in all likelihood none of them would be on a 2019 U.S. team going to Qatar that September and October because they would be in fall semester (or quarter) at school.

Granted, those numbers would vary because, for instance, 13 of the 23 are seniors now. But no matter because, of course, in just a few days or weeks U.S. colleges will welcome freshmen. Case in point: Sydney McLaughlin, the Rio 2016 400-meters sensation who this fall becomes a freshman at the University of Kentucky and by September 2019 would be a junior.

Bigger picture, at least for the Americans:

How many “emerging elite” and “development” athletes, as USA Track & Field calls the categories, will still be competing at a possible mid-August championships and, even more so, at a September 28 to October 6 world championships?

Doesn’t the question answer itself?

Because of projected lower numbers of entrants in a potential if not likely late summer nationals, the USATF championships format and time schedule could be radically different.

Same for the IAAF.

Knowing heads-up from Snapchat sticker corner: that is not rocket science.