You can like Donald Trump. You can not like Donald Trump. To be clear: I did not vote for the gentleman. Whatever. When the president of the United States of America meets with the president of the International Olympic Committee at the White House, that is a good day for the Olympic movement.

Let us all understand the gravity of what happened Thursday. Put emotion aside. Think strategically. What is in the best interest of the Olympic movement, and of the IOC? Answer: having good relations with the governments of the world. Russia is a great country and a great Olympic power. China is a great country and a great Olympic power. But, people, let’s be real.

When you understand the symbolic import of Thursday’s meeting at the White House between Mr. Trump and Thomas Bach, the IOC president, then it all makes sense: the road map from Washington in June to September in Lima, Peru, by which time — if not sooner — the IOC will have figured out how to award the 2024 and 2028 Games at a single stroke.

As this space has noted repeatedly over the past two years — that is, the duration of the 2024 (and, now, 2028) bid race — the campaign always has been a referendum on the United States.

Mr. Trump amplifies many strongly if not passionately held feelings and positions about the United States.

It’s one thing to make the 2024 campaign a referendum on the standing of the United States in the Olympic scene. It’s quite another to make it a referendum on the president of the United States — because that’s a pretext for a great many other things.

At issue is not Mr. Trump.

At issue is the strategic direction of the Olympic movement.

What’s needed now is a thoughtful, calm, level approach: what’s best for the IOC and the global Olympic scene.

Not an approach driven by emotion, and particularly emotion rooted in enmity or personality politics.

As is well known, Los Angeles and Paris are the two survivors for the 2024 Games. The IOC is widely expected at an all-members assembly in July in Lausanne, Switzerland, to give the OK to the 2024/2028 double allocation later this year, either at another congress in September in Lima or, perhaps, earlier. It’s unclear which city would go first.

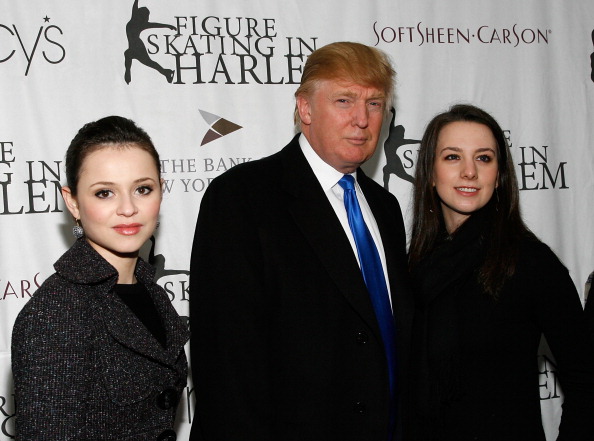

Thursday’s White House meeting, indeed, proved appropriately low-key. Details of the meeting — closed to the press — were not immediately available. As the Washington Post reported, Mr. Bach’s spokesman, Mark Adams, said at the end of the meeting, “President Trump confirmed his support for the LA candidature.”

If the IOC were smart — if it genuinely seeks to make real the directives of Agenda 2020, Bach’s would-be reform plan — it would seize the historic opening Thursday might well provide.

The IOC has been around since 1894. The opportunity of a strategic working partnership with the Oval Office — a direct line of communication — would be all but unprecedented. Especially with a president who ran a leg of the Athens 2004 torch relay and is obviously a keen Olympics fan.

Focus. Think strategically.

The meeting in DC came after a session Wednesday in New York at which senior IOC officials welcomed to the corporate sponsor fold Intel, the California-based technology company, which promised to “transform the Olympic Games and the Olympic experience,” as an IOC release put it.

Even discounting for heady PR optimism: the notion of turning the Olympics and the Agenda 2020-driven Olympic Channel into, say, a virtual reality lab would be — huge.

So — back to the referendum on American standing in the Olympic world. Two days in the United States, and the IOC president walks away with two big wins for a 21st century Olympics — a game-changing technology sponsor and a potentially enhanced relationship with the U.S. president.

Understand: with Mr. Trump, and the presidency, it’s not just LA for 2024.

On this next topic, we Americans somehow seemingly have a difficult time making ourselves understood with friends in some other places because you hear arrogance when we are talking with humility about service. So, for emphasis, we are talking about young people — potentially in harm’s way — in service to their country and potentially something bigger:

Next February, the Winter Games will be in PyeongChang, South Korea. PyeongChang is roughly 50 miles from the North Korean border. At any given moment, there are nearly 30,000 American soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines in service in South Korea. Every spring, I have the privilege to teach journalism at Seoul National University. When I’m in Seoul, I see and hear a lot of these Americans — in and out of uniform — on the subway or maybe relaxing in, say, Gangnam or Itaewon.

Same general idea for Tokyo and 2020: nearly 40,000 American military personnel in Japan, which has not had a traditional military since the end of World War II. Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe was the first foreign leader to visit Mr. Trump after last November's U.S. elections.

If I’m the IOC president, maybe it would be reassuring to have a constructive and open line of dialogue with the American president about the 2018 Winter Games, 2020 Summer Games and beyond.

As Bach himself made plain early in his tenure as IOC president, in a speech in Incheon, South Korea in 2014, it’s folly to pretend that sports and politics are distinct: “We are living in the middle of society and that means we have to partner up with the politicians who run this world.”

Moreover, on Mr. Bach’s part, it would show distinct leadership to not just address but confront the obvious multiple layers of tension — that is, the chatter around, say, Mr. Trump.

To get to what matters.

Particularly as the IOC considers its relevance in a fast-changing world — which is why the 2024, and by extension 2028, issues are so key.

For insight, let’s turn here to the coach of the NBA champion Golden State Warriors, Steve Kerr, who has been a strong critic of Mr. Trump, indeed calling the president, among things, “ill-suited to be president” and a “blowhard.”

In a podcast posted Wednesday with longtime Bay Area columnist Tim Kawakami, Kerr — asked about a potential Warriors visit to the White House — said this:

“I, like many of our players, am very offended by some of Trump’s words and actions. On the other hand, I do think there’s something to respecting the office, respecting our institutions, our government. And I think it could make a statement in a time where there’s so much divide and everybody seems to be angry with each other. It might be a good statement for us to go and to show that, hey, let’s put this aside, put all this partisan stuff aside and personal stuff aside, respect the institution.”

That is the starting place, if not the spirit, in which Bach’s visit Thursday to the White House ought to be understood.

If you are a supporter of the Olympic Games and the Olympic movement, having access to and being recognized by the president of the United States is a significant event.

Let’s take a step back.

Did Barack Obama meet at the White House with Mr. Bach or Mr. Bach’s predecessor, Jacques Rogge? Not hardly.

Especially not after Mr. Obama made the effort to fly to Copenhagen in 2009 — the first sitting U.S. president to appear before an IOC assembly — to lobby for Chicago’s 2016 bid. The members booted Chicago in the first round, with only 18 votes.

Did George W. Bush — who watched Michael Phelps swim in the Water Cube in Beijing in 2008 — meet with Mr. Rogge at the White House? No.

Juan Antonio Samaranch served as IOC president for 20 years, from 1981-2001. He met with Ronald Reagan, once, in the early 1980s, along with, among others, Peter Ueberroth. (Samaranch also, much later in his IOC term, testified before Congress, amid the Salt Lake corruption scandal.)

Before that, there was May 1980, and a very different White House visit -- the IOC president Lord Killanin meeting with Jimmy Carter. The topic: the looming U.S.-led boycott of the 1980 Games in Moscow.

Bach, since his election as IOC president in September 2013, has been collecting meetings with heads of state like snow globes at airport souvenir shops. He’s now over 100.

Even so, meeting Trump at the White House is way more.

It's history.

It validates and shows the power of the Olympic brand. It underscores the potential of the Olympics in the 21st century to do good -- if leadership can act strategically and not capitulate to wildly distracting emotion.

As deputy White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said of Mr. Trump at a briefing before Thursday’s meeting, “I know he’s certainly supportive of the committee.”