PARIS – If you were to drive around Los Angeles (people, it’s LA, we drive) and ask randos when and where the next Olympics are, odds are strong most would go, huh?

The Dodgers spend like crazy and anything less than a World Series championship this season will be treated as a failure. After two decades without pro football, 1995 to 2015, there are now two NFL teams in town, the Rams and Chargers, and the new Chargers coach, Jim Harbaugh, was last seen in his khaki pants on the way to a college championship at Michigan. The Lakers are built around LeBron James, MVP of the men’s Olympic tournament here (not Steph Curry, what?). The Clippers, don’t laugh, have a new $2 billion arena with a humongous double-sided LED scoreboard. Also, the best burrito in North Hollywood, Cilantro Mexican Grill, is in a Chevron gas station.

There’s a lot going on in Los Angeles. Always.

News alert: the Games famously were in LA in 1932 and 1984 and will be back in 2028. If you think Paris was the best ever, and it’s right up there with London, with the proviso that all Games have backstage glitches, and on TV you lived none of that here the past two weeks, none of the Olympic Village food drama, the COVID cases or, pretty much any venue anywhere, the signage that would send you on trips to nowhere — LA formally now has next.

To be clear, the bar is set high, International Olympic Committee president Thomas Bach calling these Games, which came Sunday to a close, a “love story.”

As iconic images go, it’s hard to beat the Eiffel Tower and the Olympic balloon at night in the sky over the City of Light

What Paris did, what LA now has to do, is elemental. A good, make it great – make it one for the history books – Games creates one simple thing. Easy to say, hard to do:

Magic.

“From one day to the next,” Tony Estanguet, president of the Paris 2024 organizing committee, said at closing ceremony, “Paris became a party again and France came back together.”

“Without magic,” said Michael Payne, a former IOC marketing director, “the Olympic Games are just another sports event.

“Operations,” he went on, “has to work. You will undoubtedly be remembered by the magic, not the operations — unless they fail.”

LA is not going to be, can’t be, Paris, no way, no how. After the wow of the 2008 drums at 8:08 p.m. on Aug. 8, 2008, in Beijing, people were, like, how is anyone going to top that? And then James Bond and the Queen kicked off London in 2012.

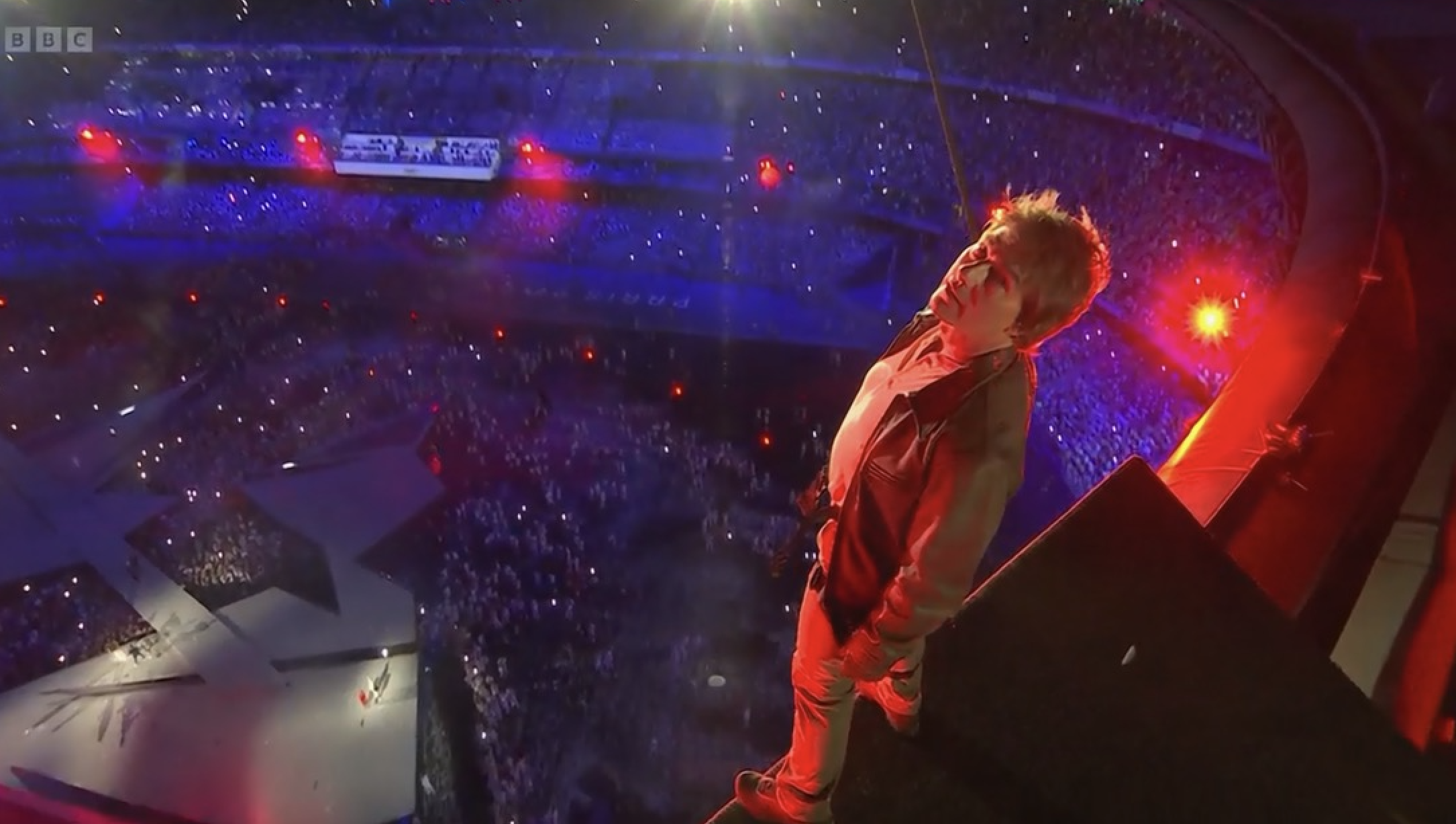

Tom Cruise atop the Stade de France late Sunday night

On Sunday night, H.E.R. sang a killer version of The Star-Spangled Banner; Tom Cruise rappelled off the top of the Stade de France; Maverick-style, he motorcyled out of the stadium with the Olympic flag; it next ended up in LA, where Michael Johnson ran it through the famed peristyle end of the Coliseum; skateboarder Jagger Eaton took it to the beach, to a Red Hot Chili Peppers jam session. Oh, and here was Billie Eilish on the deck of a lifeguard station. And it would appear Snoop Dogg made it back to SoCal because there he was, also on the beach, along with Dr. Dre, the two of them dispensing some musical wisdom.

The LA28 piece Sunday night marked the introduction to what Casey Wasserman, the organizing committee chair, said is the goal: to make the Games four years from now “authentically LA.”

He also said at a Saturday news conference, “We are the place in the world where culture is made and culture is started. And so, whether it’s our incredible history of the film industry, the music business – but LA has become so much more. Fashion and film and food. It’s all of those things. All of the star power and the opportunity to showcase that to the world that’s authentically LA.

“We don’t have an Eiffel Tower. We’ve got a Hollywood sign. We’ve got incredible venues … incredible geography. And we’re going to showcase that.”

Quick note: Snoop, Dre, Eilish — all of that was pre-recorded, in Long Beach. What’s authentic? This is ultimate LA.

What was on show in Paris was always obvious: the iconic scenery. The beach volleyball stadium any evening, the Eiffel Tower behind. The Seine, which officials insist was clean — enough. The Arc de Triomphe.

Then, the triumph of the Olympic balloon in the Tuileries at night.

Those were always imagined as backdrop for the athletes to deliver the real magic.

The freeze frame of Noah Lyles crossing the finish line in one of the great men’s 100s. Curry laughing as he sank the clinching free throws in the U.S. men’s semifinal game against Serbia, then hitting four 3-pointers, one an impossible rainbow, to clinch the final against France. The U.S. women’s team escaping Sunday afternoon with a 67-66 gold-medal victory against France because the of-course-it went-in French shot at the buzzer — a 3-pointer would have sent the game to OT — was just inside the line and only good for two.

Noah Lyles winning the men’s 100 by 5-thousandths of a second

Steph Curry shooting over Victor Wembanyama in Saturday’s gold medal game // FIBA

Day Six: Simone Biles with gold and a GOAT charm

Yes, Simone Biles. Of course, Simone Biles.

In track and field, Saint Lucia, Botswana, Dominica, and Pakistan won gold medals for the first time. Letsile Tobogo’s win in the men’s 200 is Botswana’s first Olympic gold in any sport. That Pakistan gold—Pakistan, India, and Grenada went 1-2-3 in men’s javelin.

“We are no longer a sport about one person,” World Athletics president Seb Coe said Sunday, referring to Usain Bolt, who he quickly called “herculean.”

“I cannot remember a generation of more talented athletes,” Coe said.

What Sifan Hassan of the Netherlands did raises a worthy comparison to the legendary Emil Zatopek. In Helsinki in 1952, Zatopek won the men’s 5000 meters, 10,000 and marathon. On Sunday, 37 hours after a bronze in the 10, six days after a bronze in the 5, Hassan won the women’s marathon in an Olympic record 2:22.55.

In Tokyo, she won a bronze in the women’s 1500. She is the first runner in Olympic history, male or female, to win medals in the 1500, 5000, 10,000 and marathon.

“I feel like I am dreaming,” Hassan said. “I only see people on TV who are Olympic champions.”

Racing for the finish in women’s marathon: Holland’s Sifan Hassan, right, and Tigst Assefa of Ethiopa. Hassan won, three seconds ahead // Getty Images

The Paris crowds helped encourage the final finisher in the women’s marathon to the finish, Bhutan’s Kinzang Lhamo, in 3:52.59, a personal best, in 80th place, a full 90 minutes behind Hassan and, moreover, almost an hour behind No. 79, Shantoshi Shrestha, in 2:55.06 – a moment that evoked filmmaker Bud Greenspan’s famed moment in Mexico City in 1968, when John Stephen Akhwari of Tanzania, one leg bleeding and bandaged, crossed the line and said, “My country did not send me 9,000 miles to start the race. My country sent me 9,000 miles to finish the race.”

These were those kinds of Games.

You want more magic?

In faraway Tahiti, the fifth heat of the third round of men’s surfing produced one of the most iconic images in sports history: Brazil’s Gabriel Medina seemingly walking on air, above the waves. In the sport but make-it-art world, the photo drew comparisons to the late Renaissance painter Garofalo’s Ascension of Christ (1510-20).

One of the greatest images, ever

Six centuries ago, not Tahiti

There was crazy fun, too – the Australian women’s breaker Rachel Gunn, Raygun, doing whatever that was, the routine that launched a meme explosion on social media.

The 2028 Games will be the first Summer Games in the United States since Atlanta in 1996. As Wasserman said, more than a generation ago.

Will whatever happens in 2028 be anywhere near as amazing as the hazy memories through which so many in SoCal now recall 1984?

This column was the first, in 2016, to publicly recommend the IOC award to Paris and LA simultaneously.

In 2017, this space recommended that Serena Williams light the 2028 cauldron. That’s still the choice – though it would be incredible if John Carlos and Tommie Smith, assuming both are still healthy, get the nod. Talk about closing a circle. A statue dedicated in 2005 at their alma mater, San Jose State, replicates their Black Power gesture at the 1968 Mexico City Games, one of the most enduring moments in Games history.

Allyson Felix, the champion sprinter who played a key role in the campaign that led to the 2017 double allocation, on Saturday was made an IOC athlete member. She will serve for eight years, until 2032. “Congratulations, Allyson,” Bach said from the top table.

The United States now has four IOC members. Along with Felix, Anita DeFrantz and U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee chair Gene Sykes are based in Los Angeles.

David Haggerty, president of the International Tennis Federation, is from New Jersey. The federation is based in London.

The 1984 Games generated a surplus of $232.5 million. A big chunk of that money was left in town to fund what is now called the LA84 Foundation, one of the most underappreciated success stories of all time — an organization that has given away literally hundreds of millions of dollars around Southern California to fund youth sports over the past 40 years.

For years, pushed by DeFrantz, and now by the current head of the foundation, Renata Simril, the foundation has advocated for play equity – the idea that everyone, especially girls, particularly girls of color, deserves a chance to be involved in sports.

The IOC, as part of the Paris 24/LA 28 deal, is contributing $160 million to fund youth sports in LA. That money goes to the city of Los Angeles’ parks and recreation department, to a program called PlayLA. The goal is to get 1 million kids involved by 2028.

What most people remember about 1984 is the traffic. How blessedly easy it was.

The ’84 Games also ushered in an economic upswing that saw a big chunk of what locals now call DTLA – downtown LA – built. It was a golden ride, lasting until March 3, 1991, when Rodney King, who wondered why we can’t all just get along, had an encounter with Los Angeles police. That ushered in all of the 1990s, with riots, wildfires, mudslides, the Menendez brothers, the 6.7 magnitude Northridge earthquake and, of course, O.J. Simpson.

This is why there’s a glow about the Olympics in LA.

The Games are such a part of the fabric of life in Los Angeles that one of the major east-west streets in town is Olympic Boulevard. It used to be 10th Street. The 1932 Games were the X Olympiad. After 1932, 10th became Olympic.

Referring to the 17 days of the Olympics and the 10 days of the Paralympics, Wasserman said, “We’re here for a month in 2028 but this is about the next 50 years of LA. And LA has done that twice before in its Olympic history. In 1932 and ’84, it’s really changed the trajectory of the city of Los Angeles and we hope to do that again in 2028.”

For years and years, there was a standing committee in town that would bid for the Games. As reality confronts the LA28 people, it’s appropriate to pay tribute to them, in particular the lawyer and civic activist Barry Sanders.

Los Angeles has always been different from any other Olympic city because the venues are built. The Coliseum has been there since 1923. Plus, new venues have opened since LA got 2028, in particular, SoFi Stadium and the new Clippers palace, Intuit Dome in Inglewood, both near LAX.

The famed peristyle end of the LA Memorial Coliseum as it is now

Inside the LA Clippers’ new arena, the Intuit Dome, with the wraparound scoreboard // photo courtesy LA Clippers

This means the LA28 people simply — or maybe not so simply, given the economy, as it has turned out — have to raise money. Any Games in the United States must be privately funded.

Will LA28 make the $6.8 billion budget? The former mayor, Eric Garcetti, now U.S. ambassador to India, predicted a huge surplus. Even if expectations have since been scaled back it seems reasonable to assume – famous last words – money will not be the issue. Casey Wasserman, it is said, is good at making money.

“We feel very good where we are today, and it’s our job to just stay really diligent about it,” Wasserman said.

The Olympics, meantime, are consistently about expectation – Peter Ueberroth, who ran the 1984 Games, said, under-promise and over-deliver – and then about crisis management. So, if money turns out not to be the issue, what will be?

The November election? The prospect of Donald Trump back in the White House? Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass and Wasserman are Democrats connected at that party’s highest levels.

“This is about red, white and blue. This is not about red and blue,” Wasserman said, meaning the Olympics. “We all march behind the same flag and sing the same anthem, and this is something that’s going to bring our country together, irrespective of politics.”

Transport? In 2008, LA County voters, way before the 2028 Games were on anyone’s radar, approved a tax expanding the developing rail system. A second measure got a 2016 OK. There’s construction everywhere – on the Westside, through Beverly Hills and to UCLA, which will become the athletes’ village, and, as well, at LAX, an airport you either hate to love or love to hate. In theory, there should be a Metro line in and out of LAX by the time of the 2028 Games.

Bass said the 2028 goal is a “no-car” Olympics – meaning rail lines or a fleet of borrowed buses to the venues.

Pause here. Back to the top of this column. People in LA drive. In cars.

This goal is not realistic.

For one, the Metro system in LA has a crime problem. Big time.

This headline from the NBC outlet in LA in May: “Mayor Bass says she no longer thinks LA’s Metro system is safe.” LA Times editorial, same month, following the stabbing death of a 67-year-old woman, that article noting “Transit is supposed to be the backbone of LA’s ‘car-free Olympics’ in 2028’ but recent violence on Metro trains presented an “existential threat to public transit in Los Angeles”: “LA Metro is doomed if it can’t keep bus and train riders safe.”

Speaking here, Bass said, “We’re going to need over 3,000 buses that .. we will borrow from all over the country,” and already this part of the strategy is a problem in the making, much like Atlanta in 1996, not necessarily because they might not secure the buses but because if you don’t know your way around the LA area, trying to learn on short notice is all but impossible.

You’re new here, a driver from, say, Bakersfield. You’re at the UCLA campus. Your assignment: go to Carson, to the velodrome, and get there on time with anxious athletes who have spent four years getting ready. First you have to get to Wilshire to get to the 405 and then you connect to the 110 and, then you know, you’ll get there. Saturday Night Live literally did this sort of skit, The Californians, about getting around in LA.

Never mind getting around LA. What about first getting into the United States? It’s already a concern for the FIFA World Cup in 2026.

Gun violence? We know. All of us know.

Homelessness? When I go home to LA, in just days I will start my 14th year teaching journalism at the University of Southern California. The freeway that runs next to school is the – in SoCal, we say “the” before our freeways, so it’s “the” – Harbor Freeway, the 110. The Coliseum, which will see track and field in 2028 just as in 1984 and 1932, is directly across Exposition Boulevard from campus. Exiting the 110 at the 39th Street off-ramp, just south of Exposition, there has for years been a homeless encampment – literally two blocks east of the Coliseum peristyle end, the one adorned with the Olympic rings, exactly where Michael Johnson ran through in the LA28 bit featured in Sunday night’s closing ceremony.

A June 28 U.S. Supreme Court decision gives authorities the right to clear such encampments. In response, on July 25, California Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered state officials to begin dismantling thousands of encampments. He spent Friday in LA cleaning up encampments on state property, saying he wanted more “urgency” from county leaders in addressing the matter.

On Friday in LA: California Gov. Gavin Newsom cleaning up a homeless encampment on state property

The notion that Newsom, or city or county leaders, or anyone, much less any Olympic committee, LA28, the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee or the IOC, can “solve” homelessness is … perplexing.

“We will get people housed,” Bass said at Saturday’s news conference. “We will get them off the street.” How and where: unclear.

Other things, however, can be predicted, right now, a 100% lock.

Will there be an encampment at the 39th Street off-ramp, two blocks from the Coliseum, on the night of opening ceremony, July 14, 2028?

No.