As we get older in life, we learn a few things. Human beings need hope. And we need each other.

This is the story of Ed Hula, a pioneering Olympic journalist in the United States, and Miguel Hernandez Mendez, who for most of his life has been a journalist in Cuba and is now, in significant measure because of the goodness of Ed Hula, a new American citizen.

“Olympic brothers,” Miguel said in a recent telephone call.

Miguel, left, and Ed, right, celebrate Miguel’s American citizenship // photo courtesy Ed Hula

There is much to criticize about the Olympic movement. This criticism, some measure of it warranted, pours forth every day from all over our blue dot of a world.

All the same, the modern Olympic movement, which traces to the 1890s and the French aristocrat Pierre de Coubertin, survives – thrives, now into a third century – because every single one of us on this fragile blue dot needs hope. The Olympics, at its best, celebrates humanity. Collectively and individually.

A Summer Games attracts roughly 10,000 athletes. Perhaps 10% win a medal. The rest go home and, for the rest of their lives, are celebrated as the best they could be.

As part of what is called the “Olympic family.”

One of the secrets of the “Olympic family” is it reaches well beyond the athletes. It includes members of the International Olympic Committee, the sports federations, the national Olympic committees, coaches, trainers, broadcasters, and then, journalists and sportswriters, sometimes as part of the whole party, sometimes not because, see above, criticism and warranted and all that.

The “Olympic family” is a real thing. For sportswriters and journalists, when the buzz of the deadline has gone, the television spotlight is turned off – who is still there? Who is there, really, to count on?

What Ed did – for years, way out of the spotlight, not asking for attention, not hardly – was give Miguel that thing we need. Hope.

“When there are no Olympics,” Ed said, “there are – Olympics.”

Disclosure: I have known Ed and Miguel, both, for 20-plus years.

Ed, 72, founder and editor of one of the first Olympic trade publications, Around the Rings, began covering the Games in the late 1980s and has been a fixture at every edition since Barcelona in 1992. Last June, the IOC president, Thomas Bach, awarded Ed the Pierre de Coubertin Medal.

The honor was – is – richly deserved.

Ed honored last June in Lausanne, Switzerland by IOC president Thomas Bach with the Pierre de Coubertin award, along with French historian Jean Durry // photo courtesy IOC

Miguel was arguably one of Cuba’s leading journalists. You could have found him in the pages of Granma. His LinkedIn profile shows a snapshot of a much-younger Miguel with The Greatest, Muhammad Ali.

Miguel’s first Olympics was in Montreal, in 1976. The Americans sent Sugar Ray Leonard, Howard Davis, Michael and Leon Spinks and more. Miguel is now 72, too, and remembers Montreal like it was yesterday: “Cuba! With Teofilo Stevenson!”

Ed and Miguel connected in Barcelona, in 1992. After that, they would see each other – we would all see each other – at a variety of Olympic meetings, in particular in Lausanne, Switzerland, where the IOC is based.

As the years went by, Miguel effectively was frozen out of the newspaper business in Cuba. He was, he said, expelled from the Party for articles in the foreign press. Eventually, as Ed put it, he couldn’t do daily journalism anymore. Miguel picked up some writing work here and there. But nothing regular.

In 2016, then-President Obama ended decades of isolation when it came to travel between the United States and Cuba. Americans could travel to Cuba; Cubans could come to the United States.

That March, Ed went to Cuba to pitch officials about the possibility of hosting a sports conference. While there he and his son, also named Ed, went with Miguel to a baseball game featuring the national team. There were 50,000 in the stands, Miguel said. “A historic moment, no?” The next night, the three of them went to the once-in-a-lifetime Rolling Stones concert in Havana. Miguel: “I was dancing to ‘Satisfaction’!”

A few months later, Miguel turned up in Orlando, Florida. He sent Ed an email saying he was in the States and seeking asylum. They made arrangements for Miguel to come to Atlanta, where Ed and his wife, Sheila, had long been based.

It should be noted here that Sheila Hula, who once worked at CNN and is no one’s fool, is — like her husband — one of the world’s most genuine and decent human beings. She and Ed are in every way a team.

Miguel had gotten seriously sick – gastrointestinal something – while in Orlando. Now he was better, and up in Atlanta. Ed and Sheila got him qualified for public assistance, so he could have a few dollars for essentials, and rented him a room in a house in a ‘50s-era ranch-style house in Doraville, a northeastern Atlanta suburb. Rent was $100, maybe $200.

“All we could find,” Ed said, adding, “The people who rented the other rooms were sort of sketchy people. Not of his ilk. They spoke English. They didn’t care for him speaking Spanish.”

After a bit, Ed and Sheila managed to get Miguel placed in public housing, on Peachtree Street in Buckhead, in Cathedral Towers, a high-rise tower owned by the Episcopal Church. He has been there since.

“When we had our office at Around the Rings,” Ed said, “he could get on the MARTA bus and ride it down to the other end of Peachtree. It was a good situation. This is a good life for him in the United States. For sure. After what he had been through in Cuba?”

As the years went by, Miguel decided – like millions before who had come from elsewhere – that being a citizen of the United States held distinct advantages. Ed and Sheila assuredly did not pressure him.

Friends at Cathedral Towers coached him through the citizenship test.

“I studied the history and the civics,” he said. “About 100 questions.”

“He’s very proud,” Ed said, “to say that George Washington is the father of our country.”

In November, in a ceremony in Atlanta, Miguel Hernandez Mendez was sworn in, along with a few dozen others from around our blue dot, as an American citizen.

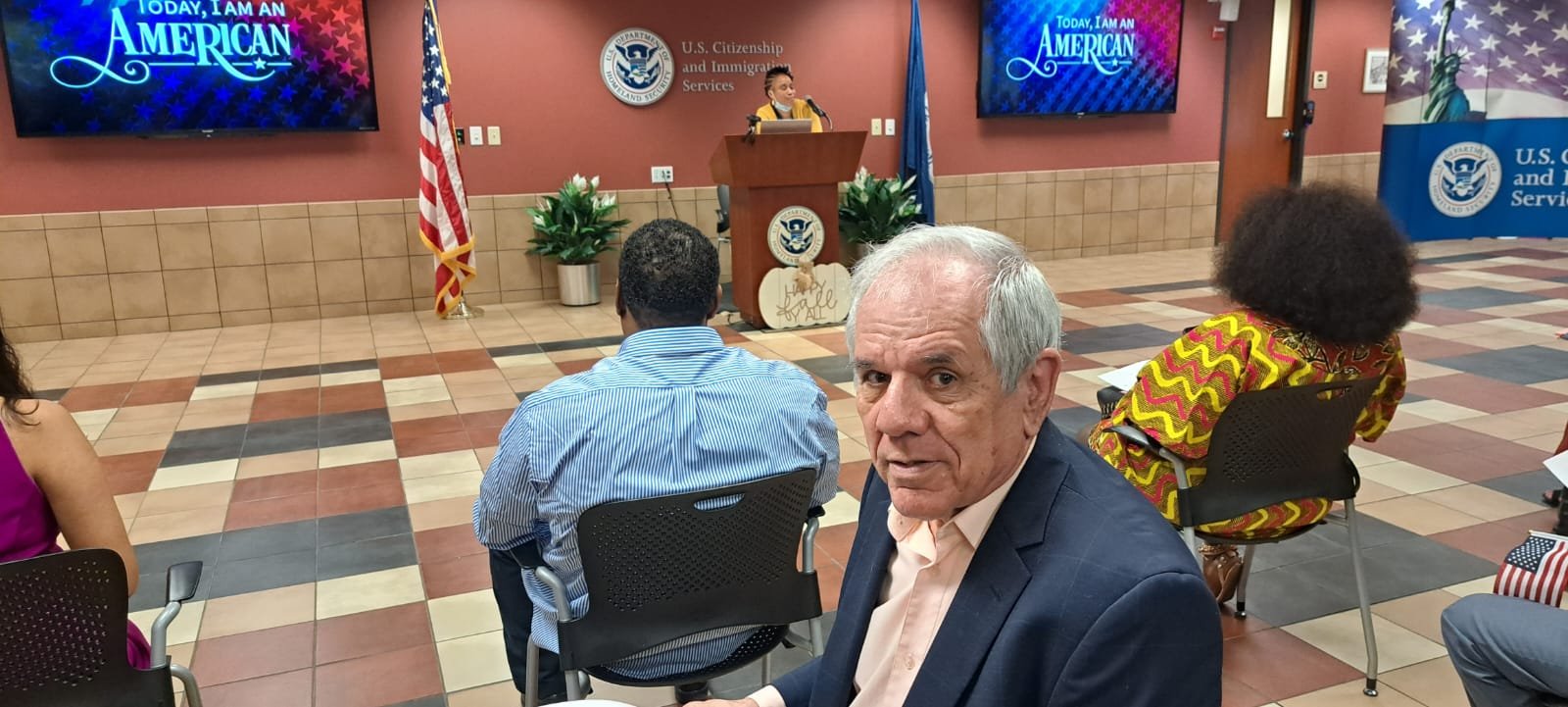

Miguel at the U.S. citizenship ceremony in November in Atlanta // photo courtesy Ed Hula

Miguel swearing the U.S. citizenship oath // photo courtesy Ed Hula

“In this country,” he said, “there is freedom. Freedom of press. Freedom of opinion. This is important for me.”

Ed was there, of course. You should know that Miguel has been diagnosed with liver cancer – the doctors say he’s responding to treatment but liver cancer is what it is – and, as the Rolling Stones remind us, time waits for no one.

“There was nobody else who was going to step up and do this,” Ed said, adding, “It was one of those things. I’m glad I did.

“The reward I got from seeing him with that citizenship certificate was one of the most gratifying things I’ve ever been involved with. I wondered how it was going to come together – if he would make it to the finish line. He had some real doubts about it. With his illness. Sometimes, he would say, ‘I just want to go home to Cuba to die.’ But no. Somehow his health improved. And his spirit improved. He’s a citizen.

“We saw it through.”

Ed paused, because both he – and Miguel, too – had been slightly shy about doing this story in the first instance. The reward for doing a good thing is simply doing the good thing. Especially for family.

“He saw it through.”