Well, here we go again with another high-profile whereabouts case in track and field, and another dose of hot takes.

How about some calm, measured, you know – facts?

The anti-doping rules are not that difficult. The world’s leading athletes should – emphasis, should – be able to follow them and, correspondingly, fans should – should – be able to understand, clearly, what’s what.

Let’s find out.

The world’s fastest female hurdler is Tobi Amusan. She is Nigerian. Now 26, she ran for the University of Texas-El Paso while in college, and was the 2017 NCAA 100-meter hurdles champion.

Amusan is the world record holder, 12.12 seconds. She is the reigning world champion.

Tobi Amusan at last year’s world championships in Eugene with her record run // Getty Images

Some background:

Amusan is the third athlete from Nigeria to be tagged in the last two years. Sprinter Blessing Okagbare, who also ran in college at UTEP, failed drug tests for EPO and growth hormone. In February, another sprinter, Divine Oduduru, who ran in college at Texas Tech, was also provisionally suspended.

Amusan has not been charged with possessing or using performance-enhancing drugs.

Over the past several years, a number of leading track and field athletes have been suspended for whereabouts failures: Brianna McNeal (Rio hurdles gold); world champions Christian Coleman (100m), Salwa Eid Nasser (400m), Elijah Manangoi (1500m); former marathon world record holder Wilson Kipsang; Garrett Scantling (fourth, Tokyo 2020 decathlon); Randolph Ross (NCAA 400m champion); Raven Saunders (Tokyo shot put silver).

Amusan says her case is due to be heard before the Budapest world championships, which begin Aug. 19. She declared on social media that she is, in all caps, a “clean athlete.”

Which has nothing to do with whether she missed three tests or not – but here we are.

One can hardly imagine (!) why the authorities wanted to test Amusan. Look at these 100 hurdle progressions, per Tilastopaja, and keep in mind she was fourth – fourth, the most emotionally challenging place of all, at the 2020 Olympics: 2018, 12.68; 2019, 12.48; 2021, 12.42; 2022, 12.12 world record. So that’s half a second in four years. Golly. Just last week, she ran a 12.34. Gosh.

Which has nothing to do with whether she missed three tests or not – but, again, here we are.

In journalism, as is often noted in this space, one is an accident, two a coincidence and three a pattern. If Amusan didn’t think after Nigerians Okagbare and Oduduru that she was going to be under the Athletics Integrity Unit white-hot spotlight, maybe she should have taken a different logic class at UTEP.

At any rate, Amusan is, of course, like all athletes, entitled to the presumption of innocence.

On Twitter, the American pole vaulter Katie Moon, the Tokyo Olympic champion under her maiden name, Katie Nageotte, offered these thoughts in a string — suggesting that it’s different for Americans.

Americans like to make like we are exceptional. But are we, really?

Moon’s tweets have gotten some traction on Twitter and again on other social media channels.

Is Katie Moon on or off the mark?

Let’s check in with one of the world’s leading authorities on the rules and regulations, the lawyer Howard Jacobs, in Westlake Village, California.

1/ It’s no different in the United States than anywhere else. Everyone in what’s called the “registered testing pool” has to provide the same info.

2/ You don’t have to list where you will be from 5 a.m. to 11 p.m. anywhere. This includes the United States. The authorities are not on you like bloodhounds on the moor.

3/ You do have to list your overnight location and training locations. Again, that’s the same for everyone, everywhere.

4/ It’s technically only a missed test if it’s during the 60-minute window. An athlete gets to pick that time of day.

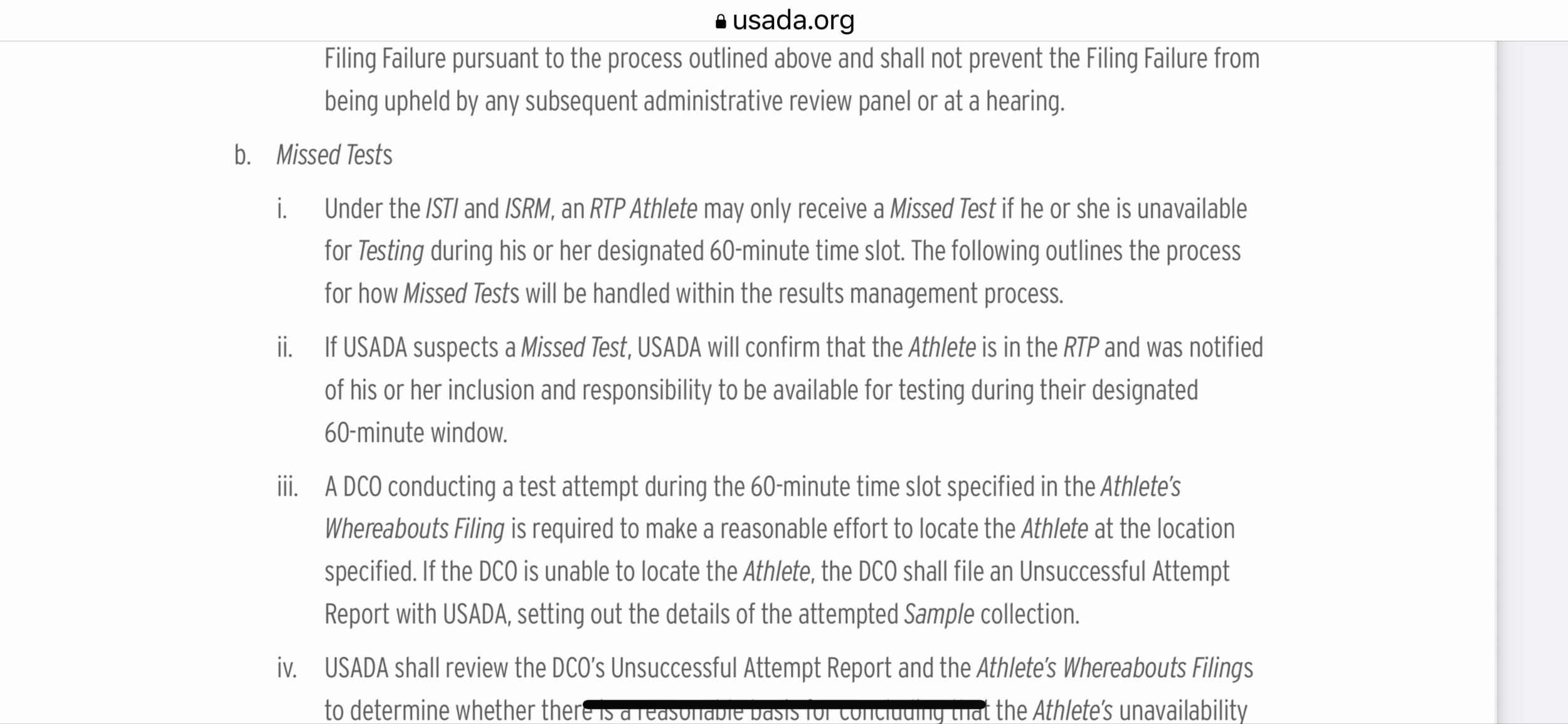

See b. Missed tests, section i — you miss a test only if it’s in the 60-minute window

So — editor’s note here, not Jacobs — when you hear an athlete bitching about, oh, USADA showed up at 6 a.m., that’s because the athlete said, I’m available between 6 and 7 a.m. at such-and-such a place. Which at 6 a.m. is typically home or the gym, right?

5/ Everything else is a filing failure.

“The whole point of WADA having guidelines is that the rules are essentially the same for everyone,” Jacobs said.

“There may be minor differences in the way whereabouts are handled by different entities,” he added, “but having been involved in whereabouts cases around the world and in numerous different Olympic sports, any suggestion that the whereabouts requirements for U.S. athletes are far more onerous than for athletes from other countries would be inaccurate.”