EUGENE, Oregon — On Sunday, the United States won nine medals, four of them gold, at the world track and field championships.

As track nerds knew and organizers helpfully reminded, this was statistically the greatest single-day haul by any nation in the nearly 40-year history of the championships.

On August 31, 1991, the Soviet Union won eight. The previous American best had been seven, on August 10, 1983. Kenya won seven medals on August 27, 2011. There have been 14 times a nation has won six.

The question is: does this nine/four performance move the needle when it comes to growing track and field in the United States? Nine and four are great, no question. But unless this meet kickstarts the sport, with an eye toward the Olympics in Los Angeles in 2028, then nine and four are just — nine and four. Numbers. Like those in that third paragraph. Stats. For freaks and nerds. Who are already on the I-love-track train.

Regrettably, track and field has an uncanny way of making it so hard for itself. There was one person on the track Sunday, one, with crossover appeal, and in the way that only track can manage, track killed him before he could shine on TV.

An official showing 110-meter standout Devon Allen the red card for leaving too soon after the gun // Getty Images

Devon Allen is a world-class hurdler who was a pretty good wide receiver and punt returner here at the U of O. In April, he signed a three-year contract with the Philadelphia Eagles after running a 4.35 40-yard dash at Oregon’s pro day.

This spring and early summer, Allen has been one of the best 110-meter hurdlers in the world. Arguably the best. The 12.84 he ran at the meet in New York in June is the fastest this year in the world. That time is just four-hundredths of a second off the world record.

When they lined up Sunday evening, there were three Americans in the final: Allen; Olympic silver medalist and 2019 world champion Grant Holloway; and Trey Cunningham, the 2022 NCAA champion.

If life was fair, Holloway would be a star the way NFL and NBA players are stars. He is charismatic and very good at his craft.

Life is not fair. Grant Holloway can walk through pretty much any airport, down pretty much any street, in the United States unnoticed.

Because of Allen’s NFL connection, he was the only person in that hurdles field Monday evening that the person track and field is trying to interest — hey, what is this sport all about — would have tuned in to see.

He also had a compelling back story. He has come back from multiple injuries — including a tear of his right ACL on the opening kickoff of the 2015 Rose Bowl. His father, Louis Allen Jr., died last month, just 63.

So what happened?

He got DQ’d.

For a highly technical rules violation.

In simple English, it was a false start. The thing is, he didn’t go before the snap. He want too soon after it.

There are by now lots of places you can read about this rule. No sense for a deep dive about it here.

This is the point:

Track and field does not have the luxury of the NFL. American football fans will remember how, in the NFC championship game three seasons ago, LA Rams cornerback Nickell Robey-Coleman slammed into New Orleans Saints receiver Tommylee Lewis before the ball got there. No flag. Nonetheless, the NFL remains the top dog in TV numbers by a mile.

When casual track and field fans drop in, like they might have been inclined to do on Sunday, and they see the one guy they might have been interested in sent off because he went too soon after the gun, they’re like — WTF are these rules? Why invest my time and energy in a sport that defies common sense?

The rules are the rules. No question Allen had to be sent off.

But why does track and field keep killing itself?

The early TV ratings, released at dawn Tuesday Pacific time, showed that some 1.925 million people tuned in on Sunday evening to watch. In all, the four Saturday and Sunday showings averaged 1.966. How many are likely to come back?

How to feel about 1.966 million? It depends. It’s maybe six times better than a regular-season WBNA game (306,000). Then again, the NBA financially supports the WNBA. Track and field doesn’t have any such luxury. And, as Rich Perelman points out at The Sports Examiner, the 2021 U.S. Olympic Trials averaged 3.183 viewers across eight hours. The 2022 Worlds are thus down 38 percent from last year’s Trials.

If you want to troll through the ratings numbers yourself — there’s a lot there — click here, at something called Skedball, via ShowBuzzDaily. You’ll see that British Open golf over the weekend whipped the track and field championships, no contest.

Spaceship Hayward at 7:20 pm Tuesday, 10 minutes before the men’s 1500 — note the sun-splashed half-full east stands

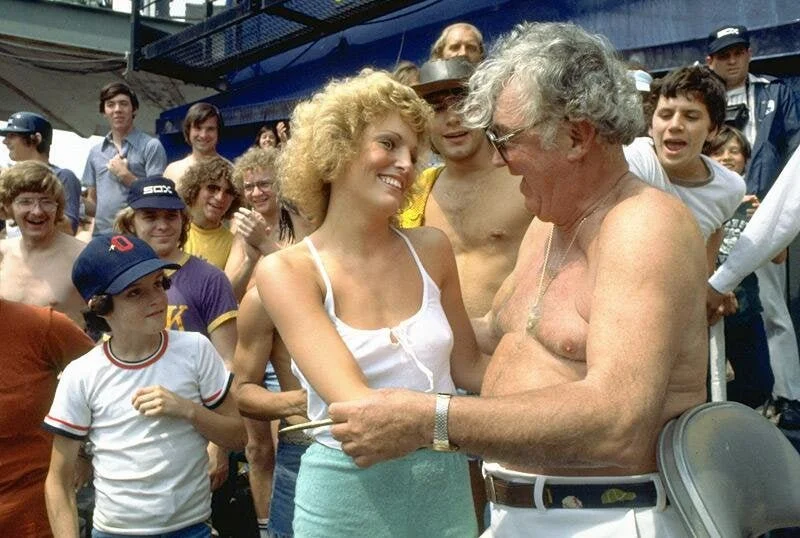

No complaining because it’s hot — ask a shirtless Harry Caray and the bleacher bums in Chicago. This was 1978

On Tuesday evening at Hayward, the sport produced two great stories. Hayward Field is purportedly the sacred holy grail, the mecca for the sport’s most devoted fans. The east stands were maybe half full. Why this can be so is a deep mystery. It’s hot over there in the sun? Diehards, baby. You don’t hear the bleacher bums in Chicago complaining that it’s hot. What about this mythical TrackTown ethos?

As the sun was setting, Britain’s Jake Wightman ran 3:29.33 to win the men’s 1500, ahead of last year’s Olympic champion, Norway’s Jakob Ingebrigtsen. Jake’s dad, Geoff, is one of the in-stadium announcers. Moments later, Seb Coe, the World Athletics federation president, who obviously knows the family, presented the medals.

Britain’s Jake Wightman at the line at the 1500 // Getty Images

400 hurdles bronze medalist Trevor Bassitt — 40 races in for 2022 // Getty Images

A few minutes later on the track, Brazil’s Alison dos Santos, the Olympic bronze medalist, won the men’s 400 hurdles in a meet-record 46.29. Americans Rai Benjamin and Trevor Bassitt went 2-3, Bassitt in a personal-best 47.39. Bassitt said afterward it was his 40th race of the season. 40th! He had prevailed and persisted after his college coach, Jud Logan, died in January; Logan was hospitalized Christmas Eve with Covid-related pneumonia.

Who will know about these stories? Beyond the hard-core track freaks who already do, or are inclined to find out?

These two races Tuesday evening were always destined to be among the meet highlights. If you wanted to see them live, streaming, great; Peacock had it. If you wanted to watch it on, you know, television, live; no chance. Tape delay on cable only, on the USA Network at 11:30 eastern.

Track and field makes it so hard. Why, why, why?