Track and field has a problem. His name is Steve Prefontaine.

This week, the lead-up to the 114th edition of the Millrose Games in New York, arguably the world’s most prestigious indoor track and field meet, marked what would have been Prefontaine’s 71st birthday.

Yet again, social media lit up with gushing tributes and grainy videos of Prefontaine races.

Lets Run linked to a Eugene Symphony planned for June 4 in tribute to “one of Oregon’s greatest champions,” the symphony an “original piece,” with fans not only urged to join to “celebrate Pre’s legacy” but to “submit a brief description of between 25 to 60 words on how Pre has impacted your life or inspired you to be your best self, or how you would say thank you to him if you could,” these notes “of tribute and gratitude, submitted by Steve’s fans from around the globe, [to] be woven into the performance to underline his impact that endures today.”

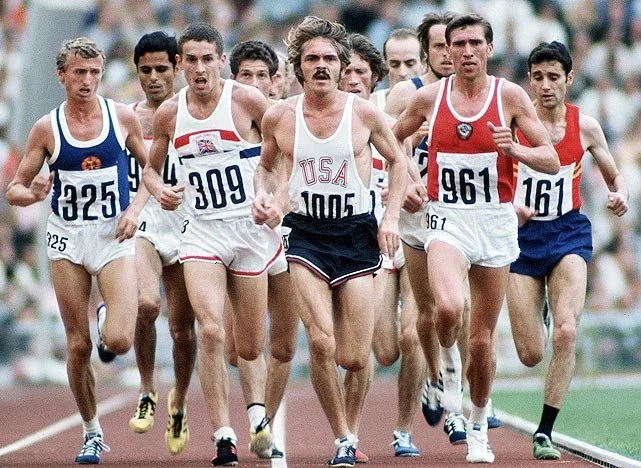

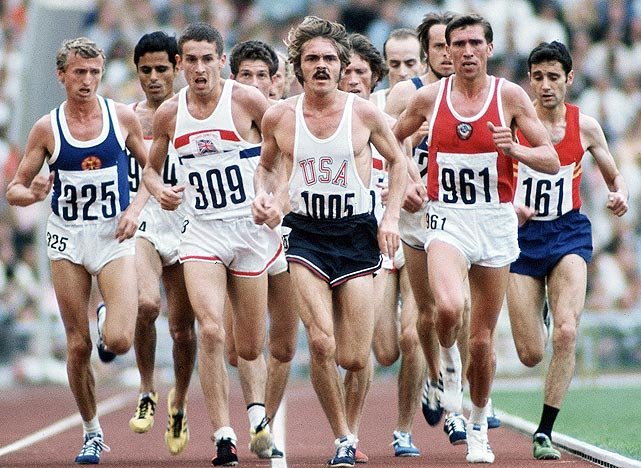

The historic Neil Leifer photo of Prefontaine racing the 5,000 final at Munich 1972 // sales@neilleifer.com | 888-802-3354

Prefontaine was, by any measure, a great and worthy champion. I am old enough to have watched him run. I was 13, almost 14, in September 1972, and remember vividly the Munich Games. They changed my life. They literally put me on the path I have been on since. One reason was the kidnap and murder by Palestinians of 11 Israeli athletes and coaches. Another: the loss by the U.S. men’s basketball team. There was Mark Spitz. Dave Wottle, who was from Ohio. Prefontaine, and the valor of his fourth-place in the 5k. And, Frank Shorter’s win in the marathon — Shorter, in particular, showing me, a scrawny little Jewish teenager in rural Ohio where football was king, that you could be someone, that you actually could achieve status in life, without playing football.

Track and field’s problem is, to be blunt, with the ongoing fetishizing of the Prefontaine legacy.

It’s why, in key measure, track and field remains rooted in Eugene when the sport desperately needs to grow its reach well beyond the Willamette Valley — far beyond Eugene, the small town in Oregon that made Prefontaine.

To be even more direct: this fetishizing, this hagiography, underscores the race and class problems that bedevil track and field.

No other professional sport in the United States pays worship to a fallen idol the way track and field does to Prefontaine.

Other sports have had young men die in their 20s — obviously well before their time.

Basketball? Len Bias.

Football? Sean Taylor.

Baseball? Nick Adenhart.

Nothing in any of these sports, or any American sport, compares to the Prefontaine hagiography.

He was a white, middle-class distance runner. This is precisely the demographic certain elements of the sport, in particular much of the running press, celebrates to disproportionate effect. Witness again the over-the-top eruption over Keira D’Amato’s American-record victory earlier this month in the Houston Marathon.

In the aftermath of her victory, on the Let’s Run message boards, one of the two brothers who runs the site, Weldon Johnson, posted this: ‘Tell me how I’m wrong: Keira D’Amato’s record is the coolest story in the sport this century.” He added in the post itself, referring to one of the site’s writers, “I just called Jon Gault with the statement above and he said maybe this decade. To prove me wrong, you must post a better rags to riches story.”

Uh, OK.

First, the best stories in track and field this century, and it’s not even close: Usain Bolt’s rampage through the sprints. Or Eliud Kipchoge’s sub-2 marathon pursuit. Both happen to be Black.

The “coolest” story, to use Weldon’s word (he and I are longtime friends, and the remarks in this column are professional observations, meaning no one should infer that they are personal in any way — they 100 percent are not), is Kenya’s Julius Yego teaching himself to throw javelin by watching YouTube videos in a country with zero field event history of note and going on to win the Worlds in 2015 and Olympic silver in 2016. Yego is Black.

Second, rags to riches, take your pick:

Athing Mu.

Wadeline Jonathas.

Non-United States: Jamaica’s Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce.

All three: Black.

The sport is rich with unconscious biases. This is why when I wrote last June amid the Trials that track and field had a race problem, my Black friends told me I was dead-on right and my white friends said, I don’t see it.

It’s nearly 50 years since Prefontaine died in a car crash. He is appropriately memorialized in Eugene, at Pre’s Rock and at the meet that bears his name.

Yet, so strange.

Since Prefontaine’s death in 1975, the United States has played host to two Summer Olympics, in Los Angeles in 1984 and Atlanta in 1996.

We have one world-class track meet in the United States — and it’s dedicated to the memory of a white, middle-class distance runner? Who ran in one Games, in 1972?

Again, this is not to diminish Prefontaine. It’s to ask why he has such an oversized stranglehold on the track and field imagination — and this must be said, to the detriment of so many other worthy American icons, a great many of whom are Black.

Because even with the calls for a reckoning following the murder of George Floyd, the sport has seemingly done nothing since — zero — to recognize, in the same way that Prefontaine is recognized, elevated, enshrined, worshipped, some of its greatest Black athletes.

Allyson Felix. After Tokyo, Felix has 11 Olympic medals, seven gold, and 18 world championship medals, 13 gold. (For the record, when Felix and Quanera Hayes, also Black, went 1-2 on June 20 at the Trials in the 400, both were celebrated, just like D’Amato, as moms. Ask Jonathas. So, again, under what theory is D’Amato the coolest of the 21st century?)

Michael Johnson. Four Olympic golds, including the two in the gold shoes in Atlanta in the 200 and 400.

Rafer Johnson. Silver in the decathlon in 1956, Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year 1958, decathlon gold in 1960, Sullivan Award winner in 1960 (breaking that award’s color barrier), lighter of the LA Games cauldron in 1984, community activist, one of the finest human beings that has ever graced these United States.

Jackie Joyner-Kersee. Three Olympic golds, in the heptathlon and long jump. Sports Illustrated for Women named her the greatest female athlete of all time, ahead of Babe Didrickson Zaharias.

Carl Lewis. Ten Olympic medals, nine gold, IAAF “World Athlete of the Century,” International Olympic Committee “Sportsman of the Century,” Sports Illustrated “Olympian of the Century,” Track & Field News “Athlete of the Year” in 1982, 1983 and 1984.

This could go on. But you get the point. Why is there not, at the very least, a Carl Lewis Invitational? The greatest athlete of the 20th century — and yet Steve Prefontaine is the one getting symphonies written for him, with invites soliciting fans’ stories of inspiration?

You see the problem?