It boggles the mind, truly, that the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency proved so inept, or something, that it moved Monday to announce it had “withdrawn” action against the world’s No. 1 sprinter, Christian Coleman.

Was its official conduct negligent or more — was it reckless? Why the aggressive advocacy bordering — in recent months increasingly typical of the agency — on religious-style zealotry? Why the arrogance?

How — seriously, how — could USADA not understand the rules?

USADA’s basic mission, fundamentally before all else, is to understand the very rules that it says, time and again, over and over, that athletes must internalize, or else.

And yet — because of USADA’s inability to understand the “whereabouts rules,” it very publicly brought a case against Coleman and, on Monday, embarrassingly — let’s be clear, embarrassingly, shamefully — dropped it.

Someone owes someone something, and before the very serious topic of money damages gets addressed, and that is a legitimate topic for discussion, because these past few weeks have been the height of the European professional track circuit, what there should be first is a very public apology, because — this was wrong.

Very, very wrong.

Christian Coleman at the US nationals in July // Getty Images

“It’s unfortunate about how the system is being operated, and Christian is a fortunate athlete,” with representation and resource, “so he was able to get by this,” Coleman’s Southern California-based manager, Emanuel Hudson, said late Monday.

“I don’t know how many others would be able to do that. I think about them.”

Hudson added, “Just like an athlete should be responsible for what they do or don’t do, USADA should as well.”

Howard Jacobs of Westlake Village, California, Coleman’s lawyer, one of the best in understanding that system, in particular the anti-doping rules, said, “It’s obvious now that it’s a case that never should have been brought. Why it was brought in the first place is probably a question for them,” meaning USADA.

He added, “It’s something that — even the charge does damage and everybody knows that. It does create a reputational stain that is not deserved.”

If you’re going to go, and hard, after the best sprinter in the world, you better have the case locked down tight. If any institution understands this, it ought to be USADA. When it went after Lance Armstrong seven years ago, there was no — zero — room for error.

Like a U.S. Attorney’s office, USADA has only so much time, money and resource. It can’t go after everyone. So when it does go after someone, it does so with a message in mind. To go after Coleman was to send a very deliberate signal: if a fish that big could be caught, then logic dictates so could anyone.

Yet when USADA decided to go after Coleman in a case that, if proven successful, very likely would have kept Coleman out of this month’s track and field world championships in Qatar and next year’s Olympics, it didn’t understand the basics — and then tried to backpedal in its very own news release, trying to fix blame elsewhere.

Very, very wrong.

At the least — take accountability and responsibility.

Just like USADA is always asking athletes to do.

Let’s unpack.

To begin, Coleman has never tested positive for a banned substance. This matter did not — repeat, not — involve a positive test. This is noteworthy. In a news release it issued Monday, USADA said it had tested Coleman 20 times total when counting 2018 and so far this year. That only hints at what’s what. Coleman’s USADA and IAAF history reveals at least 18 tests in 2018 and at least 18 so far this year— 36 being almost twice the USADA-enumerated 20. Without question, Coleman is one of America’s most-tested athletes.

Again, this matter revolved around the “whereabouts rules.” The anti-doping system depends on an athlete telling authorities where he or she can be made available for testing. Three strikes in 12 months equals an anti-doping violation. The standard sanction for that violation is two years.

So the obvious question. What is a strike? The answer: a strike can be either a “filing failure” or a “missed test.” Both of these terms have specific definitions in the World Anti-Doping Agency’s “International Standard for Testing and Investigations,” or ISTI.

A filing failure means the athlete did not make an “accurate and complete” filing enabling him or her to be accurately located, or did not appropriately update his or her filing to make sure it was accurate.

A missed test means the athlete failed to be available at the “location and time specified in the 60-minute” window specified in his or her filing for the day at issue.

Now to the facts, obtained from the defense.

USADA charged Coleman with three asserted whereabouts failures:

1. June 6, 2018, filing failure

2. January 16, 2019, missed test

3. April 26, 2019 filing failure

This is also where the case immediately falls apart.

The ISTI contains a bunch of rules and policies — often in dense legalese — called “annexes.” The annexes contain “comments” that seek to provide real-life examples offering guidance to make sense of the legalese.

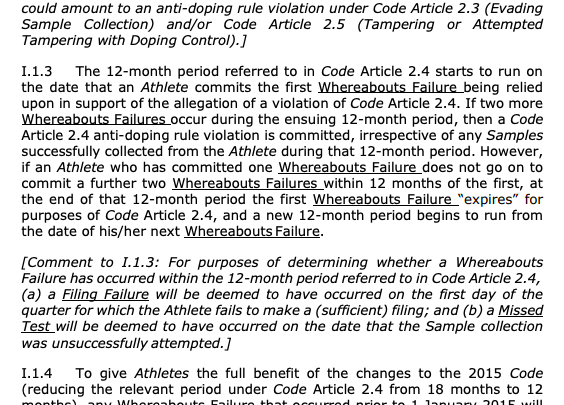

The comment to ISTI Annex I.1.3 could not be more clear.

It says that a filing failure “will be deemed to have occurred on the first day of the quarter for which the Athlete fails to make a (sufficient) filing …”

A missed test “will be deemed to have occurred on the date that a Sample collection was unsuccessfully attempted.”

The relevant ISTI Annex and Comment

This makes it easy.

The June 6, 2018, filing failure — that is then deemed under the rules to have occurred on April 1, 2018. That is the first day of the second quarter of 2018.

Follow the logic.

By 12 months later, March 31, 2019, Coleman had been notified of one additional whereabouts failure — the missed test on January 16, 2019.

The June 6, 2018, filing failure? It had expired.

For Coleman, a new 12-month period began with the January 16, 2019, missed test.

Therefore, he could have — at most — two asserted whereabouts failures: the January 16, 2019, missed test and the April 26, 2019, filing failure.

Three? Impossible. No case.

There’s so much more to this, by the way.

The June 6, 2018, incident:

Coleman’s one-hour window was 7-8 a.m. at his former residence. He also offered up 3-5:30 p.m. at a training facility. The tester showed up at the residence at 7:55 a.m.; started the “collection attempt” at 8:01; and ended it at 9:01. A call to Coleman indicated he had just gotten back into the country and was in Eugene, Oregon, getting therapy for an injury he had suffered at the Diamond League meet in Rome. He was told to update his whereabouts. It was noted he did so “before his school location began.”

On June 12, Coleman was told he’d missed a test. In a June 26 letter of explanation, he said he had estimated his length of stay in Oregon and was off by a day — that is, he got back to Tennessee a day later than he had indicated in his update.

Coleman was tested 20 days before and six days after June 6, 2018; both tests were negative.

As for the April 26, 2019, episode, which is confusing all around:

Coleman’s one-hour window that day was 7:30-830 p.m. at his new residence. He also let it be known that he would be reachable at a training facility from 2-5:30 p.m. at a facility, which is listed in another state. There’s no explaining how he might be in the two places. At any rate, the USADA tester showed up at the residence — but at 12:09 p.m. That time is not in either window. The “collection attempt” started at 12:10 and ended at 12:25 p.m.

The doping control officer — that’s the formal term — contacted Coleman by phone. Coleman said he was at the Drake Relays. Now a third state — Iowa. Coleman asked if he could be “tested at the Drakes.” The DCO said he would “let USADA know the situation.” Indeed, the DCO sent an email to USADA and got an out-of-office reply. Coleman called the DCO back and asked if the DCO “could get him the next day when he was back in [Kentucky].” The DCO said he had “no control of the test at this point and could not reschedule it,” but he had emailed USADA his location.

Critically, the DCO also reported: “The athlete updated his whereabouts prior to his scheduled practice time of the day and his one-hour window to the correct location.”

Coleman was tested both 18 days before and 33 days after April 26; both tests were negative.

On May 2, and this is also key, USADA notified Coleman of his alleged April 26 filing failure. How this amounts to a filing failure — under this set of facts — remains entirely unclear.

Why, meanwhile, is the May 2 date so important to the timeline?

Because it means USADA knew four months ago — or, in legal terminology, had reason to know — that it might well be building a case against Coleman.

And yet it did not formally confirm the alleged April 26 filing failure until July 3.

The U.S. nationals were in late July. On July 26, Coleman won the 100 meters, in 9.99 seconds.

USADA, meanwhile, waited longer still, until August 12, the Doha worlds coming up in just weeks, to charge Coleman with a whereabouts violation — with the three strikes.

This is where it really gets bewildering.

In the press release that USADA issued Monday upon its announcement of its “withdrawal” of the matter, the agency said it “consulted” with the World Anti-Doping Agency “to receive an official interpretation of the relevant Comment in the ISTI.”

That is absurd beyond words.

The comment says what it says. it says the June 6, 2018, filing failure relates back to April 1. And, indeed, that is what WADA told USADA, according to the release.

The intrigue is why USADA — which over the past several years has sparred repeatedly with WADA over any number of issues, especially the Russian doping matter — would seek to get WADA to take even a scintilla of responsibility.

If USADA opted to prosecute this case, why is it asking someone else, and WADA in particular, given the politics that have significantly soured relations between the two agencies, what to do? Responsibility for this matter is squarely on USADA, 100 percent.

Back to the USADA release. It says “this interpretation” — translation, WADA rightfully telling USADA, this one’s on you — was received last Friday, August 30.

More waiting. Instead of announcing immediately, on Friday, that Coleman was cleared, USADA waited the weekend, dropping the news on a Labor Day Monday, a holiday.

Associated Press, for one, bit, reporting both that Coleman had been cleared on a “technicality” and that WADA authorities had given him a “friendly interpretation of when the clock starts on a whereabouts failure.”

Also absurd.

This is all on USADA. For emphasis: it should never — repeat, never — have gone forward in the first instance.

“While this ordeal has been frustrating and I have missed some competitions that I should not have had to miss,” Coleman said in a statement issued through Jacobs’ office, “I know that I have never taken any banned substances, and that I have never violated any anti-doping rule. I look forward to representing the United States at the upcoming world championships.”