SACRAMENTO, California -- Five years ago, on the last night of July, Bruce Springsteen played an epic show in Helsinki, more than four hours, his longest show ever.

He and the E Street Band played 33 songs, one of which, My City of Ruins, ran to 18 minutes and 26 seconds. That song, as Bruce describes it that night, was originally written about his New Jersey hometown “trying to get back on its feet” but had since become about so much more: “what you lose, what you hold onto, the spirits that remain forever and the things you have to let go.”

About halfway through the song, Springsteen, standing at the center of the stage, says, “I’m going to stand right here. Where time can’t get me. Right in this spot.” Then with a big smile and a laugh for the audience: “Don’t you move, either.”

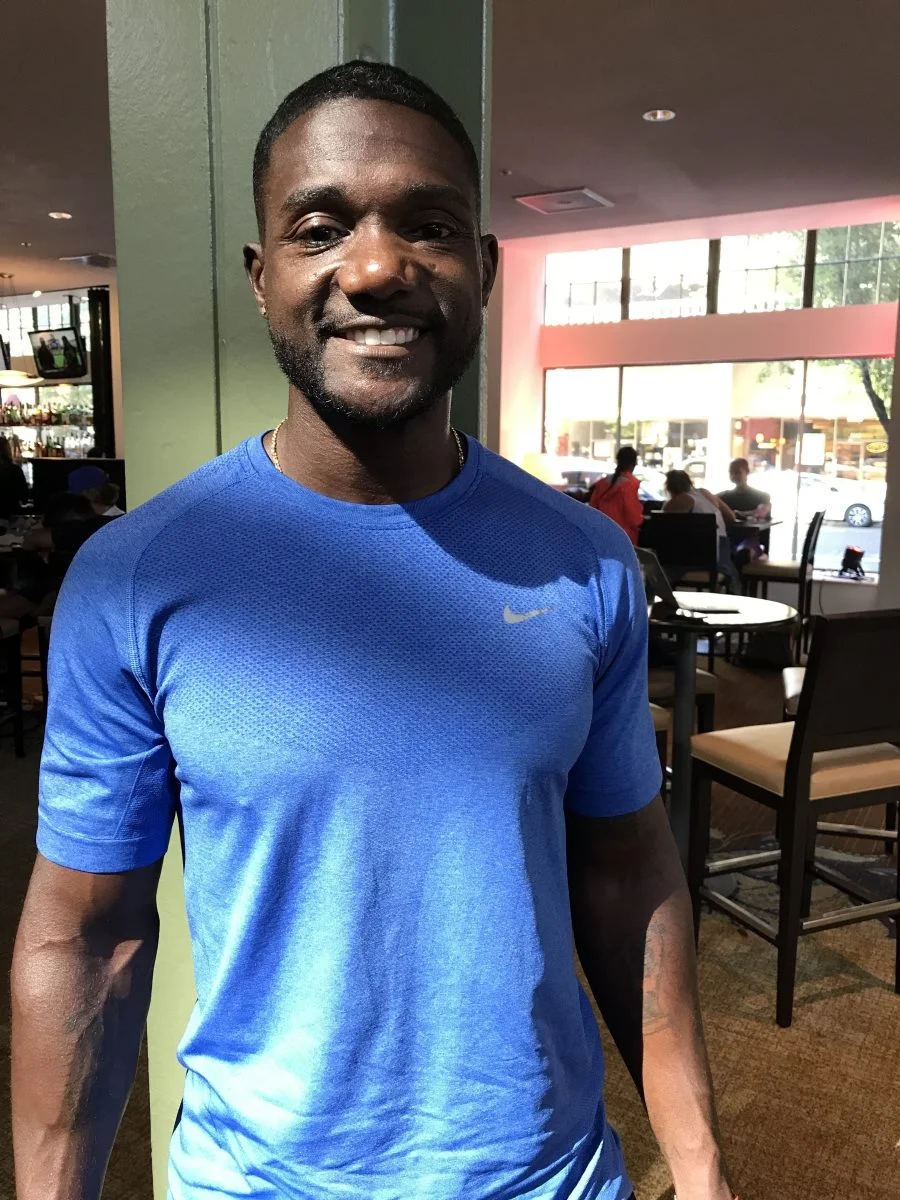

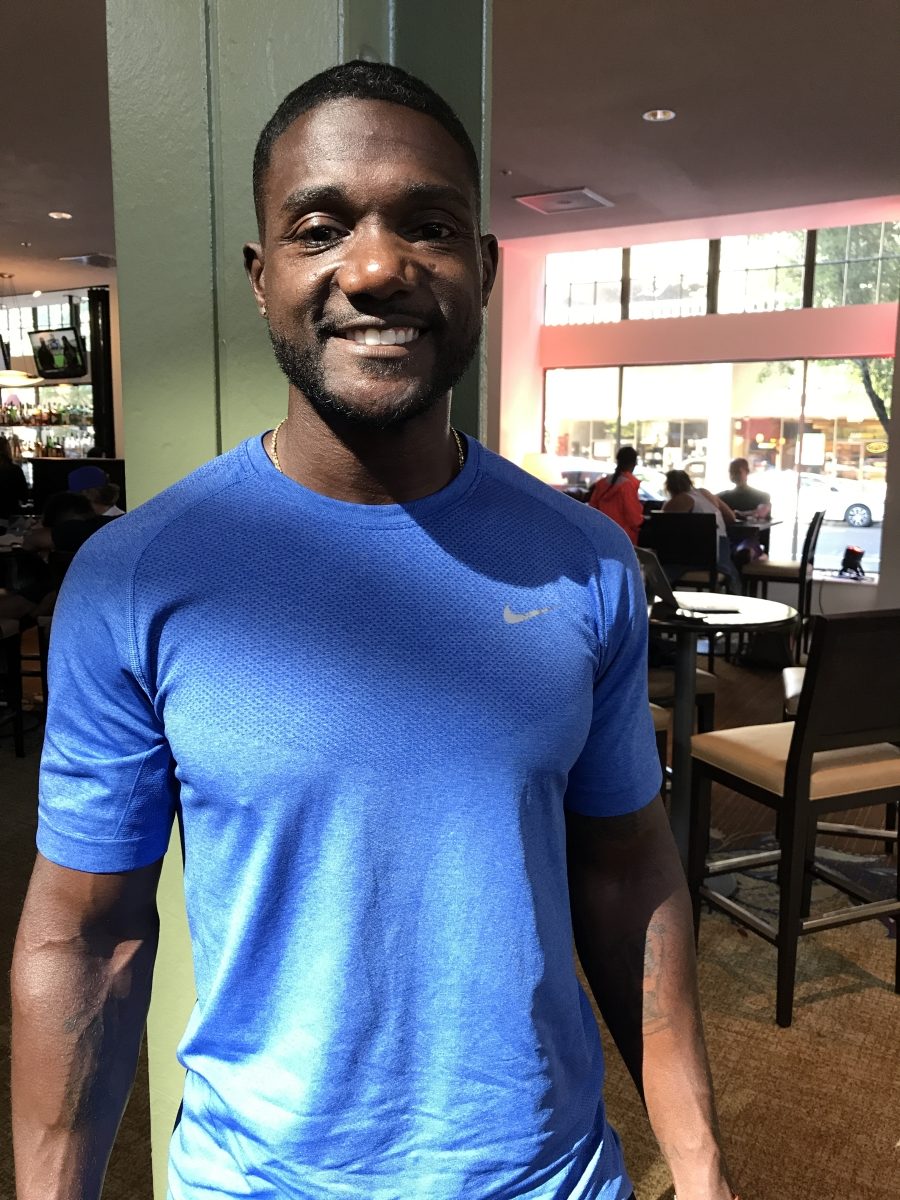

Bruce Springsteen is maybe not Justin Gatlin’s jam. Mick Jagger, neither. But that story — Justin Gatlin, who is now 35, hears that story and he laughs, too, because, as Mick once put it, time waits for no one.

For almost 15 years now, Justin Gatlin has been racing time. He knows, we all know, that time is running out. But time hasn’t quite gotten Justin Gatlin. At least not yet.

He is, for those too young to remember, the 2004 Athens Games gold medalist in the 100 meters. He is the 2016 Rio Games silver medalist in the same event.

In Athens, Justin Gatlin was 22.

Those he raced early in his years on the track have long since faded from the scene. Those he raced across the years — Tyson Gay, Walter Dix — can no longer compete at the very highest level. Those who are up and coming — Christian Coleman — learned at the just-concluded U.S. outdoor championships that Justin Gatlin is, at least for now, still the king.

And then, of course, there is Bolt.

For five years now, Justin Gatlin and Usain Bolt have been the show in the sprints, and with his victory over the weekend in Sacramento at the U.S. championships, Gatlin did his part to set up another showdown with Bolt at the world championships, coming up this August in London.

What this means, of course, is the likely if not all but certain resumption of one of the worst — the most unfair and time-worn — narratives in pack journalism:

Bolt as the paragon of all that is good and right and just in sport, Gatlin as foil and personification of all that is, well, not.

This narrative depends on any number of flawed and faulty premises. One is to believe that everything about Bolt is indeed good and right and just.

As ever, time will be the measure of all things.

In the meantime, there is Gatlin, whose story has been grievously misunderstood and who deserves far better. In particular, Justin Gatlin deserves better than to be made into a two-dimensional caricature, to be demonized by those who know of him only from reading scraps from news stories that themselves are incomplete.

Indeed, in the fullness of time, Justin Gatlin almost surely will come to be seen for what he is:

A tremendous talent who burns to compete; who is accountable, especially to the close circle around him; who has shown great passion, commitment and love for his family, friends, the sport of track and field and the United States of America.

Justin Gatlin is a real person. He is that rarity in professional sports: he is genuine. And he is now at an age where he can, and does, take stock of what has come and gone and what, maybe, is to be — bragging, appropriately, on the first-grade son who is both big and strong but, more, reads at a fourth-grade level (“He’s cerebral!”). Justin Gatlin talks knowingly about what he has lost, what he holds onto, the spirits in his life that remain forever and, as well, those things he has had to let go.

“We all have that in common,” he said, musing about time at the Sheraton in downtown Sacramento late Sunday after the U.S. nationals had ended, explaining, “We all have our losses in life.”

Then: “In track and field we all have our wins and our losses. That’s what got us here.”

—

Here is what Justin Gatlin loves most about track and field:

“It’s pure.”

You think you know Justin Gatlin from a Google search that takes 99-hundredths of a second? This is the point at which you snicker? Pure?!

Once more, the facts:

Gatlin’s first failed test, in 2001, was for medication he’d been taking for attention deficit disorder. He’d been diagnosed years before. Gatlin was at the time just 19, a student at the University of Tennessee. He tried to follow the rules. Officials said Gatlin “neither cheated nor intended to cheat.” Nonetheless, he got two years and served a provisional suspension of almost one year.

His second, in 2006, for testosterone, which earned him four years off, remains problematic. How did Gatlin test positive? It still is unclear.

Gatlin’s camp suggested a masseuse rubbed steroid-laced cream on him. A reading of the record strongly suggests that story came from Gatlin’s former coach, Trevor Graham, whose credibility, amid his extensive involvement in the BALCO scandal, has to be viewed with extreme suspicion. The former federal agent who led the BALCO probe said, on Gatlin’s behalf, “I have not obtained any evidence of his knowing receipt and use of banned substances.” Gatlin was so undone by testing positive that he volunteered to help that agent by cooperating with the feds. Gatlin did so. Did he get credit for that when his case was reviewed? None.

For Justin Gatlin, track and field is pure.

He said, “You are you when you step on that line. Steeplechase. 400 hurdles. Whatever. You are you. You win or you lose. There is no middle ground.”

The best athletes talk knowingly about a concept called mindfulness. It’s tied to hours that turn into literally years of practice. Those years can mean mental calm at a moment that calls for exactly that.

This is one of the advantages of being 35. Of understanding way more about this kind of thing.

“I realized I don’t dream a lot,” Gatlin said.

“But the night before races, I only dream about track. And I only dream about the preparation of a race. Somehow, subconsciously, I am prepping myself for the event that’s happening the next day. When I go to the competition, when I’m on the start line, it’s that same effect that Michael Phelps has when he’s on the blocks — that calm instinct, because I went through the race over and over again in a 12-hour span and now I am just tuned in.”

When he was 22, when he won the 100 in Athens in 9.85 seconds, Gatlin said, it came so much more easily physically. But even then he was a student — of the sport, of others, of himself.

“The first half of my career, it was like being in reverse. The first half, my career was being around veterans. I came out early. I learned a lot of veteran tricks. Sleep during the day, be up at night for the Diamond League meets, which were the Golden League back then, six hours ahead, little tricks of the trade to get the competitive edge,” an East Coast guy learning how to navigate European time zones, things like that.

“Once I became an older athlete, I was surrounded by younger athletes, who had a sense of respect for me because of my staying power. This generation sees I’m not just running. I’m fighting.

“I’m fighting for what I believe in.”

Which is?

“I love this community of track and field. It’s quirky.”

Do you feel the love back?

“I try not to feel about the love part. I try to focus on the respect. That’s one of the quirks about our sport. It’s a sport of what-have-you-done-for-us-lately.”

Do you feel that respect?

“I do. But I have to fight for it. I think so. It goes hand-in-hand with who I am. I am a fighter.”

He went on:

“When I was a younger athlete, I would watch track and field, and I couldn’t understand why so-and-so couldn’t run these times all the time. I mean, I could run all the time and then when the spotlight was on I performed.

“Now I understand what is important.

“In track the moment is important. The moment solidifies you in history.”

—

Two years ago, coming into the world championships in Beijing, Gatlin was on a roll.

Coming into the final, at the Bird’s Nest, where the Bolt legend began at the 2008 Games, Gatlin was riding a 28-race win streak. He had run times like a 9.74 in the 100. He had thrown down a 19.57 in the 200.

Heading into the final few meters, Gatlin was ahead. But then, nearing the line, he broke form.

At the last moment, Bolt passed.

Bolt crossed the finish line in 9.79.

Gatlin was next, in 9.80.

One-hundredth of a second.

On Sunday night in the Sacramento Sheraton, Gatlin smiled. That smile was the lesson of time talking.

“You’ve got to get over the embarrassment of losses,” he said. “You’ve got to dig through all that hurt and that pain that loss may have caused you. You realize, OK, how am I going to get over that and not let that happen again?”

Some lessons are harder than others.

Early in 2016, Gatlin rolled an ankle. It was slow to heal — it’s much harder being in your 30s than 22 — and behind the scenes 2016 proved way tougher than anybody beyond Gatlin’s closest circle knew.

Gatlin made the U.S. team in both the 100 and 200 — the oldest U.S. sprinter to reach the Olympic Games since 1912.

In Rio, he took that silver in the 100, behind Bolt.

To recap Gatlin’s extraordinary career:

Olympic 100 gold in 2004, silver in 2016, bronze in 2012. Also, bronze in the 200 in 2004. And a silver in the Athens 2004 4x1 relay.

World championship 100 and 200 gold in Helsinki in 2005; silver in both events in Beijing in 2015; silver in the 100 and 4x1 relays in Moscow in 2013.

In Rio, even after that 100 silver, that ankle “wasn’t healing right and wasn’t healing fast enough,” and warming up for the 200 in it locked up, hard.

Gatlin said, “I’m on the table, in pain, and I had at least three medical staff people for USATF trying to unlock my ankle. It wouldn’t unlock. I went out there and just missed out on the finals,” third in his semifinal heat in 20.13, missing an automatic qualifying spot by three-hundredths of a second.

Indeed, after that Rio 200 semi, Gatlin’s longtime agent, Renaldo Nehemiah, told him that missing out on the Olympic 200 final “might be a sign.” Time, Nehemiah said. You’re not getting younger: “You just need to use your talent in the 100,” Nehemiah said, “and dial it in.”

—

Nehemiah, as usual, was right. It wasn’t just the ankle — 2017 brought a series of nagging injuries.

Naturally, those injuries produced subpar performances — in early May in Doha (Diamond League opener, 10.14, fourth, outside top three for first time since 2013), in late May at the Prefontaine Classic in Eugene, Oregon (only Diamond League stop in U.S., 9.97, fifth).

This was all emblematic of something bigger.

“I felt like after 2015, after taking that loss, I came back hungry. In 2016, I rolled my ankle and worked hard to make the team. I made the team but I still didn’t feel 100 percent. I still got silver again in the Olympics. Then that whole ordeal — a year to a year and a half, two years, I felt like I had a slight depression.

“You know what? I had to realize: am I having fun with this anymore or am I not dialed in where in need to be?

“I had to re-evaluate myself. I remember asking God — God is a funny guy — I said, God, bring that fire back out of me that you once had.

“I think that the beginning of this season, all the injuries, the setbacks, the losses, Doha, Prefontaine, that made me patient, that made me hungry …

“I had to come out here,” at the U.S. championships, “and push aside all the fear I had. It renewed my hunger. Not just to run but to compete.

“I feel like in ’15, I was running fast and technically [well], and over and over again, [but] I wasn’t competing with my heart, that fire. In ’16 I was injured, banged up, not the potential I wanted to be. So I felt like ’17 had to be a year where I had to be that Justin Gatlin from the University of Tennessee. I wanted to have fun. I wanted to have that fire in my eyes.”

Just after 8 on Friday evening at a blisteringly warm Hornet Stadium, Gatlin won the 100 in 9.95 seconds.

That made him, USATF believes, the oldest 100-meter champion in American history.

Christian Coleman, who like Gatlin ran in college at Tennessee, took second, in 9.98.

Coleman is 21 years old.

The loss was Coleman’s first in a 100 since last year, when he raced Gatlin for the first time, in the Rio 2016 Trials in Eugene.

—

Justin Gatlin defeated Christian Coleman on Friday because in 2015 Justin Gatlin lost to Usain Bolt.

That moment.

“I thought about that same scenario,” Gatlin said.

“It was,” he said, “not a loss. It was a lesson.”

Those last 20 meters?

Coleman told reporters afterward that he lost momentum trying — just like Gatlin had done in Beijing — to reach for the finish line.

“I didn’t necessarily get off balance,” Coleman said, “but you slow down when you start leaning. Up until the lean it could have gone either way.

“It’s something I’ve got to work on. Up until the finish line and the lean, it could have gone either way.”

Not really, Gatlin said.

“When you’re running that fast,” Gatlin said, “everything is in slow motion. Like ‘The Matrix,’“ the 1999 science fiction classic.

About halfway down the track, Gatlin said, “I look over and I can see Coleman’s feet. I can see my legs are starting to get long. I have to match his stride. I instantly think that. I have to match his stride.”

This is experience talking.

This is mindfulness.

“I just started relaxing. I just started marching.

“About like 10 meters out, 10 and 15 meters, I can feel the momentum. I thought — I knew I had it.”

Justin Gatlin said he wants 2017 to be that year when he is running again for fun, when he feels that fire in his eyes. Heading for London, the win on a hot track in Sacramento behind him — has that time arrived?

A big laugh, and a smile: “Yeah.”