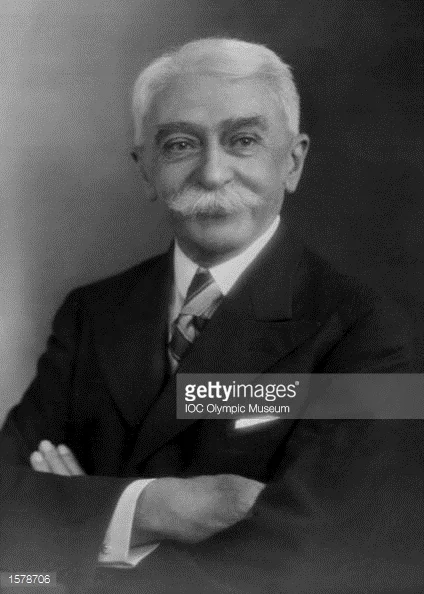

PARIS -- Welcome, members of the International Olympic Committee evaluation commission and, incidentally, jackals of the press following behind at a respectful distance and, please, do keep it respectful. This is where it all began, on June 23, 1894, the French Baron Pierre de Coubertin proclaiming to a gathering of swells, "I ... lift my glass to the Olympic idea, which has traversed the mists of the ages like an all-powerful ray of sunlight and returned to illumine the threshold of the 20th century with a gleam of joyous hope."

Here we are in 2017, and the IOC has its backside in a bind. The baron, more than a century ago, could have predicted this very thing.

Well, actually, he did. No, really. And the baron’s message is as pertinent, as apt, now as it was then:

Less is better than more. Stop building stuff. The Olympics are way better that way.

This September 13 in Lima, Peru, all the IOC members would do well to heed the baron’s message when they choose between the only two remaining candidates in the 2024 race, LA and Paris. Three other would-be 2024 cities have already dropped out — Hamburg, Rome and Budapest. Why? Because a government-backed Games costs too much, and taxpayers justifiably have other priorities.

The IOC is at a key moment in its history. The baron understood these moments.

Without further ado, reaching across the years, herewith the wisdom of the baron — not to change a word of what he said, just to add some 21st-century context:

—1911, Revue Olympique: “It would be very unfortunate, if the often exaggerated expenses incurred for the most recent Olympiads, a sizable part of which represented the construction of permanent buildings, which were moreover unnecessary – temporary structures would fully suffice, and the only consequence is to then encourage use of these permanent buildings by increasing the number of occasions to draw in the crowds – it would be very unfortunate if these expenses were to deter (small) countries from putting themselves forward to host the Olympic Games in the future.”

Los Angeles proposes the construction of zero — no — new permanent buildings.

Critically, LA already boasts an Olympic village, the existing dorms at UCLA.

LA could have opted to build a new village, downtown. That would have been a sweet jolt of urban planning. Indeed, that’s exactly the kind of thing the Olympic Games have been used for by public officials all over the world since Barcelona in 1992.

The era of Games as a bricks-and-mortar legacy factory has seen its time. Taxpayers are unequivocally, indisputably, absolutely through with it.

Change, though, is hard. It's hard to convince some observers and perhaps some within the IOC to see clearly the change that taxpayers in western democracies are demanding -- this bricks-and-mortars Olympics model sell-by date is expired.

It happens fast, as fast as Amazon changed retailing. Look how many shopping malls are now ghost ships. The IOC has to adapt.

That, at its core, is what this race for the 2024 Olympics is about, the transition that historians will write about: bid cities and the IOC recognizing and adapting to this 21st century re-definition -- rooted in de Coubertin's vision way back when -- of "legacy," and what it could and should mean for an Olympics.

Indeed, to decode the remarks Sunday evening from Patrick Baumann of Switzerland, the basketball federation's general secretary and one of the IOC's forward-edge new generation of leaders, is to understand exactly that.

Baumann heads the 2024 evaluation commission, touring both Paris and LA. In his opening remarks, he of course discussed the Paris plan for a new athletes' village, at a projected $1.6 billion -- but only after first exploring the "added value that Paris would bring to the Games ... all of the legacy initiatives," in particular "from the social and economic point of view," going on to highlight a program that already has reached two million schoolchildren.

In California, city and bid officials decided not to build that new downtown village. Why? Too expensive.

Paris, however, is persisting with the old model. Indeed, it proposes to build three new permanent structures. There's that athletes’ village in a northern suburb, near the Stade de France. There's also an aquatics complex and media housing. Together, the three projects run to an estimated $2 billion.

In his opening statement Sunday evening, Tony Estanguet, the Paris24 bid leader, said, "We believe that one of the best ways also to serve legacy and to leave legacy for Paris 2024 is thanks to the village."

That $2 billion projection: recent history has shown that such estimates prove hideously low.

In Japan, the Tokyo 2020 bid book called for $7.8 billion overall. Now it's $15 billion, maybe more. On Saturday, the Asahi Shimbun newspaper ran an editorial dissecting cost issues under this headline, "With 3 years to go, the Tokyo Olympics is already in crisis." The piece included this line, referring to the prime minster and governor's office and the entanglement of government authorities in the Olympic scene for seeming political advantage: "If so, both sides politically exploited the issue in a way that damages the image of the Olympics and breeds disgust and distrust among the public."

In recent months, activists, most potently in Budapest, have turned to social media to amplify local grievance via referendum and take aim at the establishment through the IOC and the Olympics. Almost nothing says “establishment” like the Olympic enterprise.

To believe that an Olympic project in France would be 100 percent immune from the sort of local activism that bedeviled Budapest is to wish, too, that orchids will blossom in Siberia in December. Good luck.

— de Coubertin, after the 1908 London Games, looking ahead to 1912: “It will be necessary to avoid attempting to copy the Olympic Games of London. The next Olympiads must not have such a character. There was altogether too much in London. The Games must be kept more purely athletic; they must be more dignified, more discreet; more in accordance with classic and artistic requirements; more intimate and, above all, less expensive …

“Of all countries in the world, Sweden, at the present moment, possesses the best conditions necessary for organizing the Olympic Games in a way that will perfectly satisfy all the claims that athletics and our expectations can demand.”

A historical note: the 1912 Stockholm Games would feature several notable innovations: the first Olympic use of automatic timing devices for the track events, the photo finish and a public address system.

A few days ago, Stockholm said no to the 2026 Winter Games.

The reason Sweden dropped out of 2026, nine years ahead, is because the mayor of Stockholm alleged that the IOC would not provide detailed financial information about what sort of IOC financial contribution the Swedes could expect toward a Games budget.

This is a political dodge, since the number will rough out at $900 million.

This tells you that politicians, taxpayers and — by extension, voters — have lost trust and confidence in the IOC.

Beyond the three cities that dropped out for 2024, five dropped for 2022.

Compare: in the run to the 2005 vote for the 2012 Summer Games, the IOC drew nine applicants, told four they weren't qualified and then engaged in perhaps the best race of all time: London defeating Paris, Madrid, New York and Moscow.

That was only 12 years ago.

The reason the Olympic movement has, in 12 short years, developed this enormous credibility gap is because of the very problem the baron identified after London in 1908 — the IOC keeps milking host cities, governments and the taxpayers who underwrite it all for the construction of permanent venues and Games-tied infrastructure projects.

On Tuesday, the evaluation commission is due to meet here with newly elected French president Emmanuel Macron. He is expected to affirm the French state's pledge of $1.1 billion toward Paris24.

Just some numbers to keep in mind beyond the Tokyo figures above:

Sochi 2014: $51 billion. Beijing 2008: $40 billion. Rio 2016: $20 billion probably, original estimate $14.4 billion. London 2012: $15 billion.

The 1984 LA Games turned a $232.5 million surplus.

The United States practices sports capitalism, if you will, while others pursue different forms of sports socialism. Going to Los Angeles won't turn the IOC away from sports socialism. It doesn't need to. The IOC does an extremely poor job of explaining this fact but, indeed, this is a fact: the operating budget of almost every Olympics Games runs at or close to black. It's the infrastructure costs that bleed red.

—

1925, Prague, Olympic Congress:"... in general the need has been recognized to limit the length of the Games, and thus also to limit the expenses occasioned by the Games. Yet I do not believe that these two issues are directly connected. Great savings will be realized when an Olympiad is held if that celebration is planned far enough in advance, and with great method, discipline, and disinterest. But in this area as in so many others, wasteful habits have reigned, formed through bad policy based on the idea that unrestrained luxury will necessarily result in common ease and prosperity. The issue of luxury must be reflected upon. Its vulgarity makes it sterile. It merely tends to crush moderating forces, making social contrasts a source of even greater irritation. Simplified organizational mechanisms, more standardized and more peaceful accommodations, less festivity, and especially closer and more daily contact between athletes and directors, without any politicians or go-getters to divide them—such, I hope, is the sight that the Games of the Ninth Olympiad [in Amsterdam, in 1928] will show us.”

The Paris people are aggressive and unapologetic about their strategy. On Monday, this: the suggestion that the athletes' village had to go forward without delay because of local housing needs after a would-be 2024 Games.

What, Olympic political guilt? Housing in Seine-Saint-Denis, France, is an IOC problem? Why?

This brings to mind the strategy the Paris 2012 people employed in 2005 -- when the-then mayor, Bertrand Delanoë, wanted to leverage the Olympics to gentrify an industrial area called Batignolles in the city's northwest 17th arrondissement. Came the cry: without the Olympics, it won't happen!

Guess what: Paris lost.

Guess what: it happened.

Batignolles now boasts a lovely park and substantial residential and office space.

As a British academic wrote in a 2012 essay collection, "The point about the [Batignolles] park is not that without the Games it would not happen [but rather]… the existing commercial and residential pressures within the city ensure that the urban development projects at the heart of the bids would be implemented in any case, win or lose."

On Monday, sticking to the script, as Associated Press reported, Estanguet said of the 2024 plan, "We are committed with the public authorities on this project for 2024. After that it's not guaranteed."

Michael Aloisio, deputy general director of the Paris bid, said, "All these projects have now been launched, and so they will take place before 2024, and so we can't just freeze them and kind of sideline them for four years."

Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo added, according to Reuters, "We believe in the regeneration of this area. There is a need for houses."

Again: is that what an Olympic Games is supposed to be about? A need for houses?

What would de Coubertin say?