To consider the absurdity of what track and field is considering with regard to its records, let’s turn to baseball. The comparison is apt. Both sports are heaven for stats-freak geeks.

Who holds the Major League Baseball record for most home runs in a career and, as well, most home runs in a season?

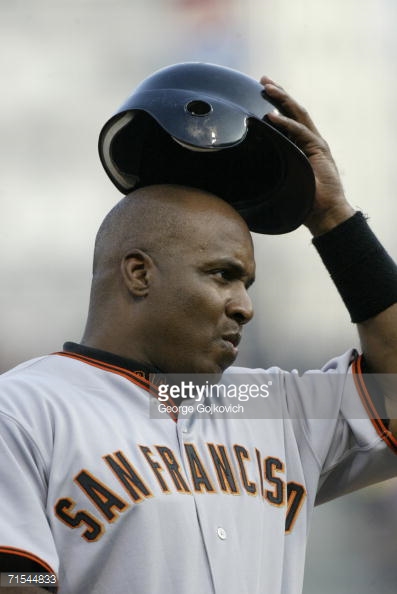

Hey, in both categories it’s that guy Barry Bonds. He hit 762 over his career. In the 2001 season, he slammed 73.

Now, does baseball say that Bonds leads the charts for guys whose hat size mysteriously, peculiarly got way, way, way bigger when he played for San Francisco as compared to the years he played in Pittsburgh? Not a chance. Bonds sits there, at No. 1.

Look at No. 4 on the all-time homer list: Alex Rodriguez, with 696. Rodriguez is an admitted user of performance-enhancing drugs. Who’s No. 4? Rodriguez.

People: what happened, happened.

This is the thing about history. It happened. You can’t say in 2017 — whether it’s baseball, track and field, tiddlywinks, whatever — that something didn’t, or arbitrarily propose new rules, like the European Athletics Records Credibility Project Team did on Sunday (the report was made public Monday) in proposing reforms that would wipe out more than half of Olympic-discipline world records from the books.

The European report is being forwarded to track and field's international governing body, the IAAF, which is said to be giving it serious consideration.

To be clear: the contributors to the European committee deserve considered respect for effort. They are good people and they mean well. Officials deserve extra marks for including Gianni Merlo, the longtime Italian sports writer and current president of the International Sports Press Association, in their deliberations. Awesome -- we’re not just running dogs!

As was articulated in the charge to the committee, track and field is purportedly beset by doping issues.

OK.

But that is not track and field’s central problem.

Baseball has had huge doping problems, too, and baseball is thriving. Track and field is wallowing. So that makes for a pretty easy conclusion: doping is not track and field’s central problem

Instead, track and field suffers from a multitude of other issues. This is what the very bright minds on that committee, and others around the world who care about track and field, should be focusing on.

For starters:

— Track and field is a professional sport. But the way it presents itself, by almost every metric, is sorely inconsistent, especially when compared against a wide range of other professional products. It is competing against those other entities for sponsor and audience attention and dollars. Pick it: European soccer, American basketball or football. Whatever. Now, how does track and field stack up?

— The best athletes don’t race against each other enough. Justin Gatlin and Usain Bolt maybe race each other at perhaps one, maybe two, meets each year. Compare: the Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees play each other 19 times each season. Why are the NBA playoffs must-see TV? Because the teams play each other every other day for two solid months, April to June. Real Madrid and Barcelona play each other all the time. In NFL football, Dallas and Washington play at least twice each season. This is a no-brainer, people!

— Track and field is sport at its essence: run, jump, throw. Yet for the average spectator, a track meet is bewildering. It’s confusing. There’s too much going on, often at the same time. And this is an awful secret: a lot of very serious track fans make like super-snobs, which is a complete turn-off to the would-be newbie fan, who just wants to know what’s going on, not get lectured about “negative splits” as if it’s Fermi and Einstein and physics at Princeton. Ugh.

— Meet presentation has barely evolved since the 1970s. There are some genuinely good track announcers out there but the PA systems at many fields are high-school quality, if that.

— Music? Lights? Fan-friendly experience? What?

— The world championships, which this year will be held in London, run from August 4-13. This is awesome for the niche of super-committed track fans, and organizers will justly point out that — just like the 2012 Olympics — the event will be sold out. But a 10-day run is a l-o-n-g deal. The U.S. track nationals are only four days. Why do the worlds run to 10?

Why, with all of that, is track and field obsessed with its records?

From the European committee report:

“… The power of any record depends on its credibility.

“If there is suspicion that a record was not achieved fairly or the conditions were somehow not correct, people become skeptical or worse they ignore it.”

Look again at baseball.

Here, for easy reference, are baseball’s top 10 single-season home run leaders. For fun, identify how many may have, you know, taken something stronger than an aspirin and those you absolutely, positively, indisputably, unequivocally know with 110 percent certainty are cleaner than Mr. Clean:

1. Bonds, 73, 2001

2. Mark McGwire, 70, 1998

3. Sammy Sosa, 66, 1998

4. McGwire, 65, 1999

5. Sosa, 64, 2001

6. Sosa, 63, 1999

7. Roger Maris, 61, 1961

8. Babe Ruth, 60, 1927

9. Ruth, 59, 1921

10. Jimmie Foxx, 58, 1932

Hank Greenberg, 58, 1938

Ryan Howard, 58, 2006

McGwire, 58, 1997

Also for fun: name the year Bonds gets elected to the Hall of Fame. Bonds landed on 53.8 percent of ballots this year; that’s up from 44.3 percent in 2016; he has five years of balloting left; historical trends suggest that players who get at least 50 percent almost always end up in the Hall by the end of their eligibility.

Reality suggests that whatever you believe about Bonds’ hat size, 73 and 762 are the numbers and he’s headed for the Hall of Fame. The relevant audience: for those who are not aware, voters for the Hall are from the baseball writers association, meaning the most skeptical running dogs themselves.

If more than half of the skeptics think those numbers are credible, and those cranky skeptics increasingly are proving willing to vote for the guy’s Hall of Fame enshrinement, he is — and the records themselves are — hardly being ignored, right?

Which holds considerable parallels for track and field, and the errant proposal to get rid of half of track and field’s records.

For one, the committee didn’t do the appropriate due diligence.

They did not, before announcing it to the world, secure the buy-in of athletes. Predictably, some of the world’s biggest stars from prior generations — the long jumper Mike Powell, the marathoner Paula Radcliffe, the middle-distance star Wilson Kipketer — were justifiably outraged. So, too, the families of former stars, including Al Joyner, the husband of U.S. sprint star Florence Griffith-Joyner.

“That’s dishonoring my family,” he told the Wall Street Journal. “I will fight tooth and nail. I will find every legal opportunity that I can find. I will fight it like I am training for an Olympic gold medal.”

Asked after a seminar Wednesday at the Milken Institute Global Conference in Los Angeles if she supported the European proposal, Allyson Felix, the nine-time Olympic medalist, said, "I guess I'm not."

She had said a moment earlier, "You don't want to take away a clean record from a clean athlete. I don't know how you solve that issue."

Further, the basis for the recommendation of this would-be policy rests on a fallacy — that “new” records can be deemed reliable because athletes who set them will be “clean” because they will have passed a certain number of doping tests.

A little background:

Samples are now kept for up to 10 years. The IAAF began storing samples in 2005. Current world records that don’t meet the new guidelines would no longer be called a “world record” but would remain on an “all time” list, according to the European proposal now off to the IAAF.

“Do we really believe,” Radcliffe wrote in a lengthy Twitter post, “a record set in 2015 is totally clean and one in 1995 not?”

Radcliffe’s opposition is particularly notable. She is close to IAAF president Seb Coe.

Indisputably, technology has advanced since October 6, 1985, when East Germany’s Marita Koch set the women’s 400-meter world record, 47.6, running in Lane One in Canberra, Australia.

But this is ever a cat-and-mouse game, and to build on Radcliffe’s notion, who is to say that someone somewhere is not using some 2017 variant of THG — the designer steroid at the core of the BALCO scandal 15 years ago. You can’t test for something if you don’t know it exists. Again, logic.

This is the flaw with reliance on any system that turns to testing. It creates in the public mind the illusion of confidence in that system. But, and this is critical, that confidence is only an illusion. That confidence is wholly false.

Look at Lance Armstrong. Consider Marion Jones. Each passed hundreds of tests.

Tests maybe can deter. But they do not prove with 100 percent certainty that an athlete is innocent of anything.

One final point.

Let’s say that track officials disregard the world’s best athletes and common sense and make this proposal the rule in track and field.

It’s not going to do what officials want. Indeed, it would do exactly the opposite. All it would do is sow confusion, which — right now, when track and field needs to simplify things and find ways to market itself to a new generation of fans — ought to be the very last item on its agenda.

Example:

For reference, Powell’s long-jump world record, set in 1991, is 8.95 meters. That’s 29 feet, 4 1/2 inches.

Let’s say, under this would-be policy, that at some meet somewhere someone jumps 8.90, 29-2 1/2. Let’s also say that’s deemed the new “world record.”

Any report from that meet — indeed, any report going forward about that 8.9 jump — would inevitably include a reference to Powell’s 8.95.

One would thus be called a “world record” when it really isn’t and one would be called a mark from the “all time” list when, in fact, it is the “world record.”

This is what happens when you try to re-write history. It can’t be done.

Track and field, you know, needs smarter thinking under that hat size, whatever it might be.