MOSCOW -- Consider what just these few weeks have brought: A massive scandal in Turkey, with revelations of teenagers being doped. A rash of doping cases in Russia. Allegations that West Germany's government tolerated and covered up a culture of doping among its athletes for decades, and even encouraged it in the 1970s "under the guise of basic research."

Positive tests involving American and Jamaican track stars: Tyson Gay, Asafa Powell, Sherone Simpson and Veronica Campbell-Brown.

Meanwhile, the election for the presidency of cycling's governing body, the UCI, is, after years and years of the sport's drug-ridden history -- and to describe it this way is perhaps even too gentle -- fractious.

In the United States, Major League Baseball moved to suspend more than a dozen players because of doping violations but the biggest star of all, Alex Rodriguez, with $95 million at stake, is fighting the matter vigorously.

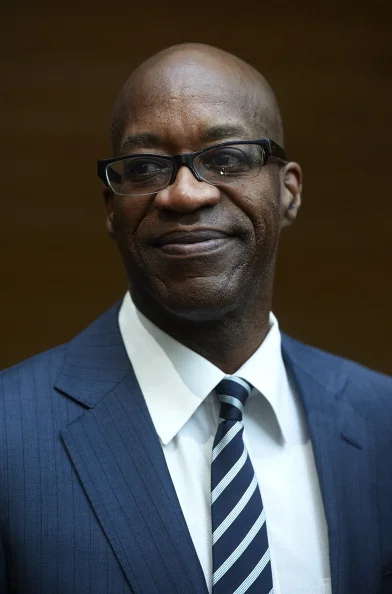

The reason Edwin Moses, the two-time Olympic gold medalist, is now in the running for the presidency of the World Anti-Doping Agency, is elemental: "I believe I am the right person to help protect clean athletes' right to compete. That," he said, "is what it is about, ultimately."

Moses, 57, entered the race to become the next WADA president in late July, becoming the third -- and final -- candidate for the job. Also in the contest: International Olympic Committee vice president Craig Reedie of Great Britain and former IOC medical director Patrick Schamasch of France.

Moses is indisputably one of the greatest track and field stars of all time. He won the 400-meter high hurdles at both the 1976 and 1984 Summer Games. He won 122 consecutive races from 1977-87.

Since his retirement from competitive running, he has been especially active in the anti-doping movement, serving since September, 2012, as chairman of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency.

The three would-be WADA presidents had until Tuesday to submit position papers to the IOC; it's now the Olympic movement's turn to nominate a successor to former Australian government minister John Fahey, who has been in the job for six years.

At a meeting here Friday in Moscow, the IOC's policy-making executive board is due to nominate one of the three. That nominee will be put up for formal election at the World Conference on Doping in Sport in Johannesburg Nov. 12-15.

Schamasch -- no one doubts for a second his technical expertise -- is considered a long-shot.

Moses got a late start. He knows that. Even so, if the anti-doping campaign is supposed to be all about athletes, who better than one of the most superb athletes of all time -- who since has virtually done it all -- looking out for athletes?

Moses earned an M.B.A. from Pepperdine University in Malibu, California. His undergraduate degree, from Morehouse College in Atlanta, is in physics. He serves now as director of the Laureus World Sports Academy, the association of sports starts that seeks to use the positive influence of sport as a tool for social change worldwide. He has served the IOC on its athlete, medical and ethics commissions and on various U.S. Olympic Committee panels as well.

"I think the position needs a person of strong will," Moses said in his first public comments since the IOC announced he was in the race, adding a moment later, "There aren't a lot of people with the experience I have had at every level."

Even so, to know the IOC is to recognize the subtle if unmistakeable signs that Reedie -- himself accomplished, sophisticated, experienced, and particularly in the ways of international sports politics and diplomacy -- may have the nomination all but sewn up.

Within the IOC, there is considerable feeling that it -- the IOC -- should play a more direct role in its dealings with WADA.

Ser Miang Ng of Singapore, currently the IOC's senior vice president, said at a press briefing Monday in London, "I feel there needs to be a shift in the IOC's stance with WADA. Perhaps the IOC should fund a higher percentage of the finance, say two-thirds, which would then justify WADA being more directly led by sport, by the IOC and by the IFs," that is, the international federations.

The IOC set up WADA in 1999. The IOC and the federations currently provide 50 percent of WADA's annual budget. Governments fund the other half. WADA's 2013 budget: $26 million.

In recent months, the federations in particular have intensified their criticisms of WADA, saying it spends millions of dollars annually on drug-testing but doesn't routinely catch the most serious cheaters. The return rate has for years hovered at about 1 percent given the usual test methods.

A more-expensive test, the carbon-isotope test, catches cheaters at a rate of about 5 percent, statistics WADA made public at the end of July suggested. But each carbon-isotope test costs about $400. Where such funding would come from is uncertain.

Moses said he understands fully and fundamentally what is what.

"I'm optimistic about it," he said. "That's the approach I'm taking …

"What I can do is lay out a philosophy: to give the athletes the confidence that the war against doping in sport is the most important aspect of competition and all the resources are being put to the task; to give these athletes the assurance that when you compete, no matter who you are, no matter what country you come from, that if you are using illegal substances you are going to be caught and sanctioned heavily."